show/hide words to know

Camouflage: use of colors and patterns to blend into the surrounding area in order to hide... more

Capsid: a protective shell around the genome of a virus.

Cell membrane: the outside layer of a cell that separates it from its environment.

Envelope: part of a cell membrane that is stolen to become the outer layer of some viruses.

Genome: all of the genetic information of an organism (living thing)... more

Homeostasis: the ability to keep a system at a constant condition.

Immune system: all the cells, tissues, and organs involved in fighting infection or disease in the body... more

Metabolism: what living things do to stay alive. This includes eating, drinking, breathing, and getting rid of wastes... more

Mutualist: a virus or living thing that grows inside or alongside a living host, helping both of them grow better than if they were alone.

Pathogen: a virus, bacterium, fungus or parasite that infects and harms a living host.

Viruses

Remember the last time you had a sore throat, fever, or cough? There is a good chance that you felt sick because your body was fighting a virus, a tiny invader that uses your cells to copy itself. Viruses can infect every known living thing. Animals, plants, and even bacteria catch viruses. Bacteria or viruses that make other living things sick are called pathogens.

Even though we try to stay away from pathogens, many other bacteria and viruses are helpful. Bacteria that live in the oceans and soil are important to cycle nutrients in the environment. Other bacteria turn milk into yogurt or cheese for us to eat.

There are even some helpful viruses and bacteria that live inside you, called mutualists. Some viruses and bacteria inside you actually help guard your body against more dangerous infections, and other viruses can help plants survive cold or droughts better. Bacteria in your gut help you digest your food and make vitamins you can’t make yourself.

If we were able to see viruses with our eyes, we would see that they are all around us. Luckily, your immune system can remove most viruses that make you sick. In some cases, doctors give us medicines that can slow down difficult viruses to help your immune system fight them.

Catching Viruses

There are many ways viruses can get into the body. Insects, like mosquitoes, can spread some viruses between people they bite. More often, the viruses that cause colds come from infected people through a sneeze or cough. Once out, they can get in your body when you inhale them from the air or touch a surface they are stuck to.

There are ways to stay healthy and to keep others from getting sick from viruses. The best way is to wash your hands. The soap can break open the fatty envelope that surrounds some viruses, destroying them. Now, soap won’t destroy all viruses, but it still helps in those cases, as it removes the oils and dirt they all stick to so you can rinse them off your skin. When you are sick, you can protect others by covering your mouth and nose when you cough. Don’t use your hands, because you can end up touching something and spreading the virus. Instead, use your upper arm and shoulder to cover your mouth and nose.

What Does a Virus Look Like?

How Big Are Viruses?

Think about this – even if we could magnify a cell until it was the size of a basketball, a virus would still only be about the size of a single period on this page.

Virus Parts

The most simple viruses have only two parts: 1) a genome (DNA or RNA) that is a blueprint with instructions for making more viruses and 2) a capsid protein shell that protects the genome. Viruses also often have proteins called receptors that stick out of the shell, and help the virus sneak inside cells.

Many viruses that infect humans and animals also have an envelope, something like a cell membrane, around the capsid and genome.

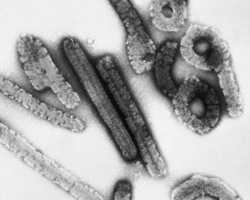

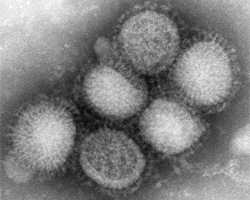

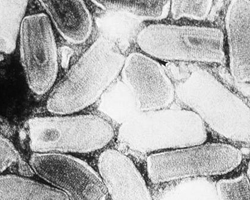

These are just the basics, though. Below are images taken with an electron microscope showing you just a few of the many different shapes of viruses.

|  |

Ebola Virus. Image from CDC Public Health Image Library | Marburg virions. Image from CDC Public Health Image Library |

|  |

Swine flu virus. Image from C. S. Goldsmith and A. Balish, CDC | Vesicular Stomatitis virus. Image from CDC Public Health Image Library |

How Does a Virus Work?

You might not think that simple viruses could take over your complex cells, but they do all the time. This is very important to viruses since they don’t have the machinery to make copies of themselves. Instead, they trick your cells into becoming virus-making machines for them.

A Virus Guide to Infecting Cells

Step one is to get inside a cell. Viruses enter the cell by tricking it into thinking it is something else that the cell needs. On the cell surface, there are sensors called receptors with shapes that fit with the shape of nutrients. When a matching receptor and nutrient lock together, the cell pulls them both inside.

A virus uses camouflage to trick the cell. Its capsid or receptor proteins look like nutrients the cell needs. When the virus receptor binds to the cell receptor, the cell thinks the virus is a nutrient, and pulls it in. Now the cell is infected!

Making More Viruses

Step two is to make more viruses. Once inside, the virus adds its genome blueprint to the cell. The cell doesn't know that the new blueprint is from the virus, so it follows the instructions to make virus parts. Now the cell has unknowingly become a virus factory. The virus parts come together to make full viruses that escape from the cell. Each new virus can infect another cell, repeating the infection cycle.

Proteins on the virus bind to receptors on the outside of a cell (1). Once inside, the virus releases its DNA or RNA into the cell (2) which instructs the cells to build more copies of the virus (3). These new viruses are released (4), either through budding (shown here) or through destruction of the cells.

Are Viruses Alive?

Viruses seem very smart to trick your cells during infections, but are they actually alive? It’s difficult to come up with one definition for life, but scientists agree on several characteristics that all living things share. Let’s see how viruses stack up.

First, living things must reproduce. Although viruses have a genome, they need to take over the machinery of other living cells to follow the virus genome instructions. So, viruses cannot reproduce by themselves.

Next, all living things have metabolism. Metabolism means the ability to collect and use energy. Chemical reactions in your cells constantly change molecules into forms of energy we can use. The energy you use to run and jump came from breaking big food molecules into smaller pieces that can be used or stored in the cell. Viruses are too small and simple to collect or use their own energy – they just steal it from the cells they infect. Viruses only need energy when they make copies of themselves, and they don't need any energy at all when they are outside of a cell.

Finally, living things maintain homeostasis, meaning keeping conditions inside the body stable. Your body sweats to cool you down and shivers to warm you up if its temperature changes from 98.6 ° F. Millions of adjustments throughout the day keep your temperature and the chemicals in your body balanced. Viruses have no way to control their internal environment and they do not maintain their own homeostasis.

So, since viruses cannot reproduce on their own and have no metabolism or homeostasis, they are usually not thought of as truly alive. They do have a huge effect on living things during infections, though!

What do you think? Should viruses be included with other living things? After you decide why you think they should or should not be considered alive, listen to biochemist Nick Lane and Dr. Biology discuss if they think viruses are alive.

- or play without flash.

View Citation

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Viruses

- Author(s): Dr. Biology

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: February 16, 2011

- Date accessed: April 17, 2024

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/virus

APA Style

Dr. Biology. (2011, February 16). Viruses. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved April 17, 2024 from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/virus

Chicago Manual of Style

Dr. Biology. "Viruses". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 16 February, 2011. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/virus

Dr. Biology. "Viruses". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 16 Feb 2011. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. 17 Apr 2024. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/virus

MLA 2017 Style

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.