Dr. Kettlewell

Menu

Dr. Kettlewell | Hypothesis | Observation | Experiment | Conclusions

Dr. Kettlewell

Dr. Kettlewell

Science requires that theories be tested to see if they are supported by evidence. During the 1950’s, Henry Bernard Davis Kettlewell ran a series of experiments and field studies to find out if natural selection had actually caused the rise of the dark peppered moth.

Dr. Kettlewell was an entomologist, a scientist who studies insects. In 1952, he was named a research fellow at Oxford, one of England’s premiere universities. He spent the rest of his life studying peppered moths and other moths known to turn dark through industrial melanism.

Scientists test theories by making predictions based on the theory. They then test the prediction to see if what they observe matches their expectations.

Hypothesis

Dr. Kettlewell thought that if natural selection caused the change in the moth population, the following must be true:

Heavily polluted forests will have mostly dark peppered moths. Clean forests will have mostly light peppered moths. Dark moths resting on light trees are more likely than light moths to be eaten by birds. The reverse should be true on dark trees. Dark moths in polluted forests would live longer than light moths, but dark moths in clean forests would die sooner.

Observation

Amateur entomologists across England helped Dr. Kettlewell map the population of light and dark peppered moths. Their work showed clearly that high populations of dark moths were found near the industrial cities producing pollution. In the countryside not darkened by factory soot, the dark moths were rare. Dr. Kettlewell compared this information with studies on the moth done in the past. It was clear that the dark moths were almost completely absent before the Industrial Revolution. Now they were found only where the forests were polluted.

Experiment

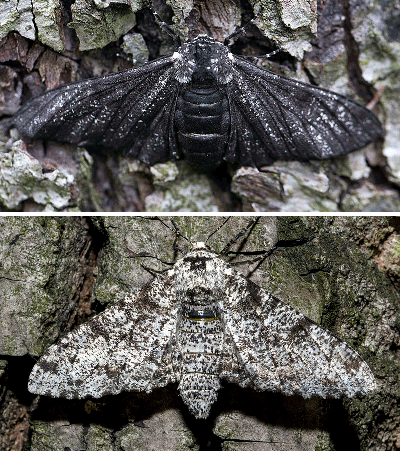

Light (top) and dark (bottom) peppered moth. Image by Jerzy Strzelecki via Wikimedia Commons.

To directly study bird predation on the moths, Dr. Kettlewell placed light and dark moths on the trunks of trees where he could observe them. He recorded the times a bird found the moth.

He found that on dark tree trunks, birds were twice as likely to eat a light moth as a dark moth. The same birds would find the dark moth twice as often if the bark on the tree was light. This supported the idea that dark moths had a survival advantage in a dark forest.

Dr. Kettlewell also tested the idea that dark moths live longer in dark forests. He collected groups of light and dark moths. All captured moths were marked so that they could be identified if recaptured. After marking them, both groups were released into the wild.

Two days later, moth traps were used to recapture the moths. In clean forests, twice as many light moths lived to be recaptured as the dark moths. Only half as many light moths were recaptured in polluted forests. He had experimentally shown that if the moth's color matched the environment, it had a better chance of survival.

Conclusions

In 1959, Dr. Kettlewell published an article in Scientific American summarizing his studies of the peppered moth. His years of work made an excellent case for natural selection. Every prediction he made had withstood the test.

In a dark forest, the dark peppered moths were shown to have a survival advantage over light moths. Birds were twice as likely to eat a light moth as a dark moth. Rare before factories were built in England, their increase in numbers was shown to be related to pollution. Natural selection was the best explanation for the change in the moth population over time.

To watch natural selection in action, continue onto the peppered moths game.

Menu