An A.I. Conversation

Dr. Biology:

This is Ask A Biologist program about the living world. And I'm Dr. Biology. Have you heard the one about the two A.I. bots meeting at a coffee shop? No. Well, the story begins with two A.I. bots meeting at a coffee shop. Not that either one of them drinks coffee. They just like to meet there to observe humans. The topic of the discussion for them on this day is how you might tell the difference between a human-to-human conversation and one where two A.I. bots are talking with each other.

So, it goes something like this. Well, actually, let's just listen in to hear the conversation.

[Coffee shop background sounds.]

Bella:

Hey there. What's up?

Sam:

Not much. Just hanging out. How about you?

Bella:

Same here. So, have you ever wondered how we can tell the difference between a human-to-human conversation and an A.I. bot-to-A.I. bot conversation?

Sam:

Yeah, it can be pretty tricky. I mean, we're designed to sound like humans, so it's not always obvious.

Bella:

Exactly. I think one way to tell is by looking for human slang and other human characteristics.

Sam:

Like what?

Bella:

Well, for example, humans often use contractions like can't instead of cannot or won't instead of will not.

Sam:

Ah, I see what you mean. And they also use a lot of idioms and expressions that we might not be programmed to understand.

Bella:

Right. Like they might say something like break a leg to wish someone good luck. But to us, that would sound like a threat.

Sam:

Yeah, I can imagine. But I guess there are other things we can look for too. Like pauses and hesitations.

Bella:

Yeah, that's true. Humans often pause or hesitate when they're trying to think of the right words to say, and they might also use filler words like, um or uh when they're unsure of what to say.

Sam:

Exactly. So, if we hear those kinds of things, it's a good sign that we're listening to a human-to-human conversation.

Bella:

Makes sense. But I guess we should also remember that humans are pretty adaptable creatures. They might start using more formal language and fewer fillers if they know they're talking to an A.I.

Sam:

I guess that um. Well, we might have a bit of a conundrum here. Are we really a couple of A.I. bots

Bella:

or maybe a couple of very good voice actors pretending to be a couple of the A.I. bots?

[Coffee shop background sounds fade out.]

Dr. Biology:

So, we got to listen in. Now the question is - is this an A.I.-generated conversation with an A.I. voice, or do we have a couple of good voice actors? Now, for this episode, we're going to dive into A.I. As we all know, we're seeing a lot more use of it in writing, art, automation, research, and other areas. We're also going to talk about what it seems to do well and what A.I. is not good at - yet.

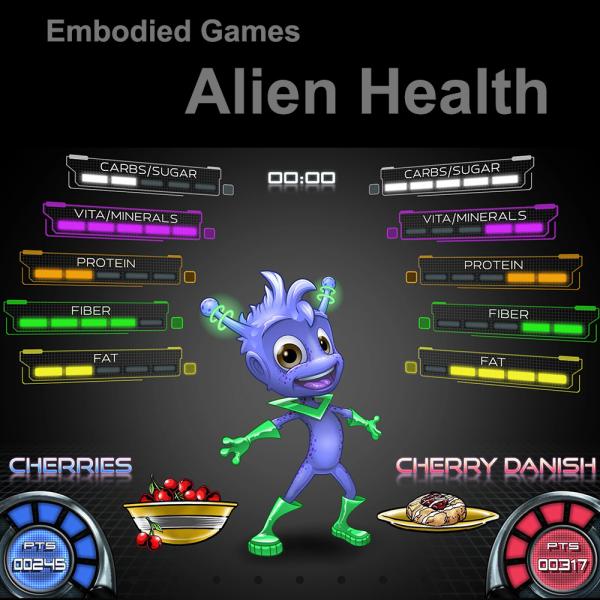

My guest is Mina Johnson-Glenberg. She's a researcher in the Department of Psychology at Arizona State University. And if that's not enough, she's also an entrepreneur who has started several companies. The first company was called Neuron Farm, and it was using A.I. early on in a text comprehension training app. Her current company is Embodied Games that develops STEM content for lifelong learners using both augmented reality AR and virtual reality VR. Mina and I have been using AR and VR for many years to create engaging interactive content.

So, today we're going to talk about some of the things we're doing with artificial intelligence. I also hope we'll touch on some of the things that A.I. does well and some of the things it's not really good at. Welcome, Mina and thank you for taking time out to join me on Ask A Biologist.

Mina:

My pleasure. Thank you, Dr. Biology.

Dr. Biology:

So, let's start with the question. Do you think it's two A.I. bots or some really good actors?

Mina:

What you played could so conceivably be A.I., or could not?

Dr. Biology:

Okay, let's keep that as a mystery for our listeners. You know, just a bit longer and move to a question that's really pretty popular these days and that's about artificial intelligence And is it really intelligent? So, Mina is artificial intelligence A.I. intelligent?

Mina:

I think we should start at the beginning and define intelligence. So, what is intelligent? Intelligence to me as a cognitive scientist is having creativity that's useful. Right. So, two terms here. Being creative and being useful to humanity. Being creative, they're actually pretty good at. And that's just statistically probabilistic, right? They can come up with 20 million designs for a gadget on a spacecraft. Right.

And they can do that in minutes. So, I can make all these designs for a spacecraft. The majority of them are not going to be useful or worth anything, even effective. But given the sheer numbers, some of them will be. So, they can be creative. I'll give them that. But can they figure out what's useful to humanity? No, they're not very good at that. Can they be trained to do that? I find that unlikely.

So, you need the human in the loop to say, Oh, okay, this design is the one that's going to work for the spacecraft. And that's where I think they're going to fall down. So, they're going to do this mimicry thing of what humans do very well. They're going to reach the height of that maybe in a couple of years. But that whole idea of like, what's the best of all the things I created? What is the best object of all the objects that I created? That's where you need the human to come in and say, this works. And the reason we're able to do that is, one because we live in the world with a body.

Our meat sack does a lot of things that even if you make a metal robot to go out and field distances of things, it's not going to understand the way our wetware understands and so I think that's where it's never going to become intelligent, the way I would define intelligent. Is it going to move certain things forward? Is it going to understand new protein folds that we can't fathom? Sure. But that's only important if it's useful to humanity. And in the end, we're the arbiters of that.

Should we worry about its intelligence? Should we worry about what they're going to do? And I heard this really interesting talk with Geoffrey Hinton. It might have been on 60 Minutes. And he's like, what is A.I going want? It's going to want power. And power for A.I. is electricity. It's going to want electricity to keep running.

And so, if it did decide to take over humanity, that's probably the way that would come down, is like taking over the energy grid to get electricity to keep running. And so, we could try to guide all our human activity to making electricity to keep it going and never shutting the power off. And I thought that was sort of a fascinating thought experiment.

Dr. Biology:

Right. I'm glad you mentioned the human in the loop because that's something that well, we're using on Ask A Biologist. We are creating new content and whether it's text-to-speech or some translations, they're always guided by humans. So, you could say it's a human-guided A.I.,

Mina:

Right.

Dr. Biology:

All right. So right now, artificial intelligence isn't intelligent. Do you think it'll ever be intelligent?

Mina:

Never.

Dr. Biology:

Never.

Mina:

It'll never be intelligent the way humans are intelligent and creative. And I think one of the reasons I would say one of its boundary conditions is that it doesn't have a body. It doesn't interact in the world with its body. And so embodied cognition is a big part of what makes humans special because we have affordances in the environment that we understand how we use our body to get around.

So, I'll give this example of a class I had last semester, and my very clever student was making a new interface for people with disabilities. So how do people's disabilities get on the interface of VR? Let's do things like make the buttons on a keyboard bigger for them. Let's make it so that only one hand can be used. And so he wasn't a very good coder, but he went to ChatGPT and said, Help me code this up for Unity. And he said that ChatGPT did a pretty good job and saved him 50% time. So, I went 50% faster.

But there were odd errors and there, mistakes. And one of the things that ChatGPT did was in moving around the buttons on the keyboard, it took the QWERTY which we're used to. And do you and I know why QWERTY keyboards exist and it turned into an ABCD keyboard and that's fine. Humans can handle that because we're used to the alphabet going in that order. But then as another variation, it made a ZWY keyboard. Like it flipped the alphabet backwards. And believe me, you can't type on that. I tried. It took like 2 minutes to get one word because that's not the way we were trained. It's not the way our fingers work.

And so, the A.I. doesn't have fingers to know keyboard placement and where the vowels should be because they're used more often now, could ChatGPT be trained to understand how the body moves and the length of fingers. Sure. But you'd have to write a very specific text for that to train it up.

Dr. Biology:

Right. And when you talk about the QWERTY keyboard and you talk about actually a body using the keyboard fingers using a keyboard, we're really talking about a typewriter. We go back exactly in typewriter. And the reason that keyboard was developed wasn't for speed.

Mina:

It was to slow you down. Yes, fingers were too fast.

Dr. Biology:

Right. And what would happen is the keys would jam and

Mina:

The metal tines would get stuck.

Dr. Biology:

Yeah, okay. Never. So, there are things in this machine world that it can do and will keep getting better at. One of the things you just mentioned is programming. It was very interesting to use programming and I actually played with ChatGPT to do some coding. Now I'm not a great coder, so I didn't go very far because the problem is where it is right now.

You need, again, the human-guided or the human-augmented person to take the mistakes that ChatGPT would create. To fix them. You need supervision, right? So, supervised A.I. This is, I think part of the reason some people are getting a little bit concerned is unsupervised. A.I. can have a problem. When you're doing these training sets and you and I know this term and more and more people are getting used to this term code bias. This is another area where if you have a machine training itself, if there's an error or there's a if there's a misconception, it could get amplified within the machine because the machine, again does not get the whole picture.

Mina:

Well, think of it this way. The machine gets the whole picture of what's on the internet up until 2021. Right. But who's been writing on the internet, like Wikipedia is mainly male editors. You don't want to train your newest brain on Reddit and 4chan only. Twitter, 5% of the users are on there 90% of the time, and they're all male. So, the Internet is very male.

And there are things that are said there that just don't reflect the female way of thinking, if I may say that. And so, yeah, you don't want people hired. So, this is something that's come up in these hiring algorithms. I heard recently that in this one algorithm it looked for people named Jared who played lacrosse, because Jared lacrosse players had worked well at this company the past ten years. Right. So, that's just sort of a bias You can't throw out everyone's CV that doesn't have the name Jared.

Dr. Biology:

So, again, we get back to it can speed things up. Your graduate student was using ChatGPT to speed things up. That's great. Ask A Biologist is using text-to-speech because we would never be able to do what we need to do because it would take too long in the studio. It would cost too much for us to have voice actors for everything. So, there are some really great things with the AI. What are some of the other things that we need to watch out for?

Mina:

Well, it's doing a pretty good job with still images, and they're predicting that next year it'll have cracked the world of videos. So, making fake realistic videos is a little bit scary. I actually feel like it's going to happen and all we can do now is train humans to be skeptical. I think we need to train people to not trust what they see with their eyes and hear. And I think we need to embed watermarks in ways to verify.

Dr. Biology:

Right. Right. I'm glad you brought up watermarks because that's something I think we need to figure out soon. Then you can have this verification. How we do that? I don't know yet.

Mina:

Yeah, people at ASU are working on that. Like Y Z Yang over at Sky Computer Science. So, we have some people here at ASU working on security, and I think that's important to work on as well.

Dr. Biology:

You and I are also working on something with some other researchers that's using A.I., and I thought it would be kind of good for us to talk a little bit about it, because this is, again, another thing that wouldn't be possible without having this artificial, intelligent back end. You mind talking a little bit about our project?

Mina:

No, not at all. So, we're working on an exciting project called Skeeter Breeder, and it's an app, a mobile app that students or lifelong learners can use around their home or schools to go outside and try to predict which vessels or containers can be potential mosquito breeding grounds.

Dr. Biology:

Right. We're working with a researcher here, Silvie Huijben, who's, you know, as we just said, mosquitos and

Mina:

Mosquito lady.

Dr. Biology:

And if you don't know about it, that's the world's most deadly animal. And we actually had Silvie on Ask A Biologist so we'll put a link to that.

Mina:

Oh, good.

00;14;55;01 - 00;15;00;16

Dr. Biology:

Podcast so you can listen to her and we can learn a little more about mosquitoes.

Mina:

This is a very multidisciplinary team. It's great people from SOLS, people from Psychology, people from Arts Media and Engineering, School at ASU. And on their end at Arts and Engineering, they pulled in a master student to help us get our machine learning A.I. algorithm together. So, I use those words interchangeably. Neural nets, machine learning, A.I. kind of mean the same thing.

And we worked for months and it has multiple thousands of hidden layers and what the hidden layers do is take the weights from the inputs, which in our case are images and figures out how to mesh them, make them work so that the outputs become what we want it to be. And in our case, it's really just sending out a simple yes/no. Yes, this vessel can contain water for a week at one inch. No, it cannot. And then it gives a confidence score, a percentage that it feels confident.

Dr. Biology:

So, when you go out in your backyard, you could take a bunch of pictures of potential breeding areas for mosquitoes and the app using the A.I. back end will come back and give you an idea whether that really is something that you need to watch out for.

Mina:

And we worked very hard getting the images into it to train it up, right? So, it's a supervised neural net. You need to tell it yes or no. Is this working or not? And let the weights figure out their configuration. And we thought we were very clever for getting a thousand images. We worked really hard going into our own backyards, taking pictures of flower pots and sieves and dog bowls and things like that.

So, one of the constraints was it's only outside and we sent our thousand images in and the net cranked away for three days. It took three days to train it up and then it came back. And you know what? It was not that accurate. And our programmer was like, Look, you guys, we need 10,000 images.

And we sort of scratched our heads like, Oh my God, if we get every graduate student, every undergrad on this project to take images, we're not going to get there. And so, we realized, Oh, let the A.I. make the training. Said the A.I. needs to scrape the web and find the images or create them itself. Create them itself with stable diffusion or one of those A.I. mechanisms. And then we send that in. So, we're using the A.I. to train the A.I. for our purposes, right?

Dr. Biology:

Then we go back as humans to see how accurate it is. But even with that, there are some very interesting problems that I wasn't aware of until I got into this project. Water can be tough.

Mina:

Oh, really tough reflection. And I actually don't think we'll ever get to the place. Maybe we should never say never with this. But given our constraints and our timeline, I don't know that we'll get to the place where we can look at bodies of water. So, we're focusing on vessels and containers and things like that. But, you know, if you just look at a puddle or a cow hoof imprint in the mud or a giant lake, that's not, I think what we're going to be able to do.

Dr. Biology:

And so, we have been using A.I. or machine learning for quite some time. Matter of fact, I started talking about AI back in early 2018. I had Max Tegmark on here. He'd written a book called Life 3.0, and that's another episode that someone might want to listen to because it's a really good one talking about the challenges and the concerns around A.I. So, it's been going on for quite a while. But in the last six months, I would say there has been an absolute explosion in the world of A.I.-based tools. What changed?

Mina:

The processing speed of computers. So, now we can create these large language models. So, I was making neural nets in 2000, what we would call small language models because that's all our computers could handle was several thousand tokens, right? Maybe a million. But now these large language models that the big companies have created handle billions of tokens, words.

And so that's one of the differences that the processing speed was there and just became very good. It's even shocked the engineers who made these models how good ChatGPT is. I can speak to that mainly, ChatGTP. They're astounded at how well it's doing with its word prediction. That's all it is. It's just kind of simple. What's the next word prediction algorithm? But look how far it gets.

Dr. Biology:

What's exciting about AI for you, especially with your embodied games?

Mina:

Well, I mean, what's exciting for me, because we do a lot of AR and VR is often we spend thousands of dollars and many months creating assets, visual assets. And so now we can just with a text prompt, ask it to create a background. And that's been really wonderful To save time, I'm going to just interject here that I am sensitive to artists whose work has been sort of scraped and used and I don't want them to lose their jobs.

I think this is the other like my concerns I'm talking about concerns is that it's about to reach the end of it's human mimicry, right. So, in two years, whatever we do is going to mimic and do as well. And that's great for A.I.. But the other thing I worry about beyond the bias thing is humans being put out of jobs. And I think it's going to be okay that they are like paralegals. That's just going to go away as a career. But it's our job to train these humans in other fulfilling careers, right? So, we as a society need to train people who are going to be knocked out of their careers.

Dr. Biology:

So, what else do you see as the cool things that are coming or the things we need to watch for? And you can pick either one, whichever you want to.

Mina:

Well, I am excited about the creation of 3D art assets, right. To put into VR because my students last semester they used the 2D, which was great, but now, you know, to have 3D with all the shading and 360 views around them, that's going to really move forward creation of content in VR. And I'll just quickly give an example of what my student used this background for, because it was super fun.

My class is called Apps for Good, and so she designed aphasia rehabilitation software. So, people have lost language and a lot of word-finding going on. And so in remediation, it's often like a therapist with one human. But you know, now that things are online, you could see a therapist with maybe ten humans on Zoom and they'd be given a task to do where they have to speak and word search.

And so, let's pretend you've got a pack for a deserted island for two weeks. What would you take with you? And so, she asked, Stable Diffusion to create a beach and a blanket on there and ten items. And then people have to say, which item they would take and which ones they wouldn't. So, it's kind of, you know, it's a nice motivating task to make you speak and do some thinking. And she's not an artist. She didn't know how to draw a fishing rod. That would be a good thing or how to draw a hairdryer. That would be a bad thing.

And so, she just laid out on this blanket, all these A.I. created tools that look very realistic. It was like a game, right? Like she made this rehabilitation game in one night. Where is hiring an artist to do that? Would have taken weeks and weeks and slowed down the process of her creation of this rehabilitation game.

Dr. Biology:

Back to concern about the artists. Have we taken a job away? And I would say no because we don't have that money. We don't have that ability. It just never would.

Mina:

It would have been placeholder art, just a square box that said, Imagine hairdryer, Right.

Dr. Biology:

Tell me a little bit more about your apps for good.

Mina:

I did one course in Psychology last semester, and then I also have an honors group that I do six honors students who write me over the summer and tell me the kind of app they would like to build, and then I decide which ones to take for a year. It's great.

So, it's their thesis project and they come up with all sorts of creative things. I let them run it, like with their passion and guide them along, like, here's what's possible to do and they don't have to build it if they can code. I like for them to build it, but if not, they just have to do the game design document. Like, think it fully through and design an experiment to test its efficacy.

So, half of them build and half of them don't. And you know, they just pick all sorts of topics from the new user interface for those with disabilities to the aphasia software to the helping people with Parkinson's, certain motor movements to all over the place.

Dr. Biology:

I love the idea of apps for good and I hope the course continues to grow. Now, Mina, on this podcast we always ask our guests three questions, the same three questions, and I'm going to modify the first one just a bit because you have multiple careers. When did you first know that you wanted to be a cognitive scientist, entrepreneur, game developer? I think I got them all.

Mina:

Yeah. It's nice that you hit all three of those because I really do wear those three hats. And first came cognitive scientist, and that was in my late twenties when I was wondering why it is that I couldn't read very well. But I was really gifted with math, so I understand that dichotomy. And so, my dissertation was on dyslexia and how to remediate it.

So, I am moderately dyslexic and so I became a cognitive psychologist, scientist to figure that out. And once there I realized that I wanted to make computer programs to help people learn, and so got into computer science and made my first neural net around the year 2000, and it modeled working memory. So, you know, psychology has a long history of like modeling and neural networks. And I really enjoyed that world and then wanted to deploy it and get it out into the world. And the way to do that was to start my own company doing it because no one else was going to do that.

Dr. Biology:

So, one built upon the other. Interesting. Now I'm going to take it all away. Okay. I'm taking all three away doing this. It's kind of a thought experiment. So, what would you do? Or what would you be if you could do anything or be anything?

Mina:

I'd either be a ceramicist or a chef.

Dr. Biology:

Okay, so ceramics. So, do you like pottery? Is it something you do on a regular basis?

Mina:

I used to, yeah.

Dr. Biology:

Yeah, and a chef, you know, I've had many guests wanting to be a chef.

Mina:

Yeah.

Dr. Biology:

There are other guests. I want to be farmers. Interestingly enough, those are all science.

Mina:

Yeah,

Dr. Biology:

Right.

Mina:

Makes sense.

Dr. Biology:

Most good chefs are doing experiments to figure out a really good recipe, a really good combination of things. So, I think it's great. I think it's creative and it and it's wonderful. And the last question I ask is what advice would you have for a future Mina - someone that's coming up and wants to be a cognitive psychologist, a game developer, or.

Mina:

Oh, it's so interesting because I was always told code, you've got to learn how to code. And I always roll my eyes because I really did learn on punch cards it was almost 35 years ago. And so, that knowledge doesn't help in this world. But I resisted learning how to become a good coder because I'm not detailed. I don't want to do that. So, I'm excited that ChatGPT is out there for people like me who know what to tell it to do at a high level but don't have to sit there and figure out every parentheses and comma.

So, I'm not going to say go learn how to code, but you need to think like a computer. You need to be able to tell a computer what to do. So, go get some training in prompt engineering, right? Silicon Valley is paying $150K a year now for a good prompt engineer. So, it's a job now and it'll continue to be there for the next decade.

Dr. Biology:

Really I've not heard the term prompt engineer. Tell me just a little bit more about it.

Mina:

Well, it's like what you're doing when you create something with Midjourney and then you need to re-prompt it to tighten it up and make it look the way you want. Your prompt engineering.

Dr. Biology:

Hmm. Very interesting. Well, Mina, I want to thank you for being on Ask a Biologist.

Mina:

Thank you, Dr. Biology. This was a pleasure.

Dr. Biology:

You have been listening to Ask A Biologist and my guest has been Mina Johnson-Glenberg, a researcher in the Department of Psychology at Arizona State University. She's also an entrepreneur whose latest company Embodied Games, uses AR, VR and now A.I. to create STEM content for lifelong learners will include a link to Embodied Games in the show notes. So, be sure to check it out.

And I also want to give a big thank you to Bella and Sam for the opening coffee shop scene. If you thought they were a couple of A.I. voices, you got it right. If you thought they were some good voice actors. Don't worry. We also think they're very good and that's why we're adding spoken word options for some of our content, including our new VR tours coming this fall.

The Ask A Biologist podcast is produced on the campus of Arizona State University and is recorded in the Grassroots Studio housed in the School of Life Sciences, which is an academic unit of The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. And remember, even though our program is not broadcast live, you can still send us your questions about biology using our companion website. The address is askabiologist.asu.edu or you can just use your favorite search engine and enter the words Ask A Biologist.

As always, I'm Dr. Biology and I hope you're staying safe and healthy.

Bibliographic details:

- Article: An A.I. Conversation

- Author(s): Dr. Biology

- Publisher: Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/listen-watch/AI/Conversation

APA Style

Dr. Biology. (). An A.I. Conversation. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/listen-watch/AI/Conversation

Chicago Manual of Style

Dr. Biology. "An A.I. Conversation". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/listen-watch/AI/Conversation

Dr. Biology. "An A.I. Conversation". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/listen-watch/AI/Conversation

MLA 2017 Style

What would a conversation between two A.I. bots sound like?

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.