What’s Been Cooking at SICB?

Dr. Biology:

This is Ask A Biologist a program about the living world. And I'm Dr. Biology. In this final episode of the SICB podcast, series, we sit down with two of the people who've been driving a lot of the activities at the conference, including some dance performances we talked about in an earlier show. Kim Hoke is an associate professor in the Department of Biology at Colorado State University. And Nate Morehouse is an associate professor in the Department of Biological Sciences and the director of the Institute for Research and Sensing at the University of Cincinnati. He's also one of our former Ph.D. students. And when I say our I mean the School of Life Sciences at Arizona State University.

Both Kim and Nate are exploring how animals communicate and why they behave the way they do. Each of them has been deeply involved with the Spatial-temporal Dynamics in Animal Communications Group. That's the one that invited us to the conference to do these podcasts. This band of scientists are focused on animal communication and how communication is impacted by the space the animals are in and their movements for this episode, we learn about how this group came together.

We also get a tiny bit of the story about the favorite animals of these scientists, which leads me to a riddle in two parts. What's the favorite game for a butterfly, a jumping spider, and a frog? And who usually wins? Now you can take your time. You can think about your answer while we jump into the conversation with our scientists.

[Sound of the conference in background.]

Kim, thank you for joining me on Ask A Biologist.

Kim:

Thank you, Dr. Biology.

Dr. Biology:

And Nate welcome back to Arizona.

Nate:

It's great to be back and good to see you.

Dr. Biology:

Now for people that don't know it, Nate got his Ph.D. at Arizona State University in the School of Life Sciences. So, he's been fully indoctrinated into Ask A Biologist.

Nate:

[Laughter] That's right. I've been listening to it for years now.

Dr. Biology:

Everybody knows if they don't what happens, we won't tell anybody. That's right. [Laughter]

Nate:

Let them discover on their own.

Dr. Biology:

Now, the two of you, when you go to a science conference, they're big. So, we typically break them up into sections. And you actually have a section of the SICB that you're doing. I want to talk a little bit about what you organized. One is dance performances. It's interesting to have heard the scientists that were watching these dance performances, not just, you know, oh, that's cool or that's unusual. They were thrilled. It was almost like kids in a candy store.

Nate:

Yeah.

Dr. Biology:

So let me start it off with Kim. You two are the collaborators on this. You're the instigators. When did this all start?

Kim:

Well, the very original meeting was that I saw Nate give a talk, one of these 15-minute talks four years ago at the SICB Conference. And I was captivated and realized that we had a lot of interests in common, but we hadn't crossed paths because we also had many differences. That meant we often weren't in the same section of the conference. I'm not good at recognizing people, but I happened to see Nate again going into another talk. And I said, You! We have a lot in common. We should really talk.

So, we exchanged numbers, and we met up later and had a fantastic conversation about these shared interests that we had and realized that we both thought about how animals communicate from really different perspectives. But really wanted to understand the dynamics, the variation, depending on where they are in the environment and timing. And this was something that we could really approach from different perspectives.

Dr. Biology:

I love this because I've gotten your view of what that encounter was like. So, I got that communication What do you remember, Nate? [Laughter]

Nate:

Well, you know, I'm always open for a good conversation. I remember sitting out in the afternoon sun in Tampa, Florida, really just getting excited together about what we could do to bring people together from really different perspectives on this question of how animals move around space over time when they're communicating.

Dr. Biology:

Right. We're not talking about just what we're doing here. It's moving. We've had guests on from the conference. We're talking about snakes. We've got robotics as well. I mean, yeah, absolutely. Lots lots of things going on. Whose idea was it to introduce dance?

Nate:

This is an interesting thing. I would have a hard time pinning it on any single individual in our group, because what happened after Kim and I had that initial conversation is we invited some other voices into the conversation, and it was the dynamics of that group that really began to think outside the box. And so, it's hard for me to pin some of the ideas that have emerged from the group on a single individual. I think they've emerged from the dynamics of a really great and diverse set of people working together.

Kim:

I agree. And so from the three years ago or four years ago meeting, we had done a workshop together. We got a group of people in the same room and sort of coalesce some small working groups to write papers together. And then they worked together for a year. We had a symposium, and as part of that symposium one dance professor, Valerie was brought into our cluster. But it was really the whole synergy of the group that led to let's have an actual set of dance performances at SICB.

Dr. Biology:

Talk about animal movement. There's a great example, and they produced some really wonderful pieces.

Nate:

Just a broader comment. I think one of the things I love so much about science is that somebody you've never met before can walk up to you, start a conversation and it can lead to this international collaboration between the sciences and the arts really naturally. It's a beautiful thing, this ability to connect so easily over common interests in the sciences.

Dr. Biology:

Right. We don't often think about that, and I think the stereotypical view of the scientists is the lone scientist in the lab with a white lab coat looking through a microscope all by themselves. Let's talk a little bit about the science with this group within SICB. What are the three main components that you would talk about?

Nate:

Well, one is movement. That's critical how two animals move around in space. And how do they manage that movement when they're communicating? I would say another element of it is cognition and the neural side of things. How do the brains and sensory systems make sense, not only of the movement but of the communication that occurs within that? And the last theme is about cutting-edge tools that are just being developed, even right now to help us to track movement, to understand animal reactions in real-time, sometimes, sometimes even feeding back into interacting with the animals through robotics or animation.

And this is really an exciting moment for these themes to come together because we have the computing power. We have deep learning, machine learning, artificial intelligence now beginning to contribute to these things in ways that were really not possible. Even about five years ago. So, bringing in those cutting-edge tools that enable us digging deeper into these questions is another key theme for us.

Kim:

And it may seem obvious in retrospect that if you're talking about communication, you would think both about the animal moving and displaying and also about the animal responding and sensing. But actually, they're often quite different fields that are contributing to those pictures. And so even just bringing those pictures together fully, it's not unique. Other people have done that, but I think it's really valuable for the field to say, Yeah, communication is both what you want to say and what you get across.

Dr. Biology:

Right. It actually brought a different appreciation of robots because when it was first introduced to me that scientists using robots, I hadn't thought about the fact that there are some cases where you can't have a particular animal in the field doing what you wanted to do to test your hypothesis. To see if that behavior is doing what you think it's doing for many reasons. And the only way to do that is to create a robot version So that was one of the things that was really amazing to me. You know, robots to me are like Robby the Robot from Forbidden Planet [Laughter] or if you want to go a little more modern, Transformers or if you're in a factory floor, it would be the yellow robots that are doing repetitive motion.

Nate:

Sure. We oftentimes think about robots as reproducing what humans do, the type of robotics that we're really engaging with is robots that do what animals do. That allow us a little bit more control. Animals are very difficult to get to do what you want them to do on cue. You know, of course, the movie industry has trained animals that do that, but that's not something that scientists are particularly interested in.

So, if you can work through robotics and robotics are making leaps and bounds, advances in our ability to, for example, have a robotic lizard do a particular display, and then you can put that out in a real environment and look at responses of other lizards and his wild other lizards will take that lizard at face value and think it's a real lizard and sometimes even fight with the robotic lizard. And so that's a testament to the fact that you're actually getting some real response out of the animals by using these new robots.

Dr. Biology:

Right.

Kim:

And it's so valuable to identify by what the animals really care about, because you can change the robot in very minor controlled ways. You know what you changed, and you can see, does the response of the responding animal, does it change? Does it like this better or worse? Does it care?

Dr. Biology:

Well, we've been talking about the conference, which is great. It's exciting. But let's get back to something. It's probably a little more near and dear to your heart. Kim let's talk about your research.

Kim:

OK.

Dr. Biology:

What would be the number one thing from this meeting that's going to help you on your research? And actually, let's talk about your research.

Kim:

OK, well, I can just start out saying my lab does a couple of different things. One is we study communication mostly using sound in frogs. So, if anyone's been to a frog pond at night, the frogs are there making a lot of noise. And that's the typical communication setup where frogs are finding their mates. And we know a lot about that from a behavioral perspective. So, the things that I'm really interested in are understanding how the brain of the animal listening to that sound how does the brain determine that animal's response? And how does that feedback and change what's a good song to sing? What's a good sound to make in a particular environment in a particular species?

OK, well, I can just start out saying my lab does a couple of different things. One is we study communication mostly using sound in frogs. So, if anyone's been to a frog pond at night, the frogs are there making a lot of noise. And that's the typical communication setup where frogs are finding their mates. And we know a lot about that from a behavioral perspective. So, the things that I'm really interested in are understanding how the brain of the animal listening to that sound how does the brain determine that animal's response? And how does that feedback and change what's a good song to sing? What's a good sound to make in a particular environment in a particular species?

Dr. Biology:

So, you can record the mating calls of the frogs and you could play them back, obviously. Have you modified them on all? Have you tried to play your own versions?

Kim:

Yes. And that's one of the amazing things about some species of frogs. They will respond to a taped call so well. So, we don't have to have robots. All we have to have is a speaker playing a sound and a female frog in reproductive condition will sit there, walk towards the speaker and jump at the speaker for 30 minutes trying to find the mate. So, people have done for many years slight variations in the sound, big variation in the sound, change those sounds, and see does the female care? What does she respond to? So that's one of the reasons frogs are such a great system for understanding this. Their signal is really quite simple. And you can make a lot of manipulations to the signal and get a really clear readout of the response. [Play an example of the frog signal below]

Dr. Biology:

Excellent. How about you Nate, last time I left you it was the world of butterflies.

Nate:

It was we still study butterflies. We're studying jumping spiders now as well. We're really interested in how animals make decisions based on what they can see. And one of the interesting things about vision is that animals see the world by moving through it. Vision is really an activity. It's not a passive sense. It's an active sense. And we're really interested in how animals are using vision to probe the world around them, to investigate it, to make choices How do they focus attention?

The world is a really bewildering set of sounds and smells and sights. How does the brain side of things help to make sense of that? How do they focus their attention? And in contrast, maybe slightly simpler. I think you're selling the frogs a little short [Laughter] that they're that their calls are simple. But we're oftentimes working on animals that have crazy complex displays where they're waving around legs and they're bright colors and patterns and they're making vibratory sounds. How does the receiver make sense of all of that? Why is that proliferation of complexity evolved?

A lot of it, we think, has to do with chasing attention, with capturing and retaining attention on the part of whoever you're communicating with. So, we're really interested right now and how animals make sense of the complexity of the world around them, how they concentrate their attention and how the communicating animal is working very hard to keep the attention of, for example, a female mate.

Dr. Biology:

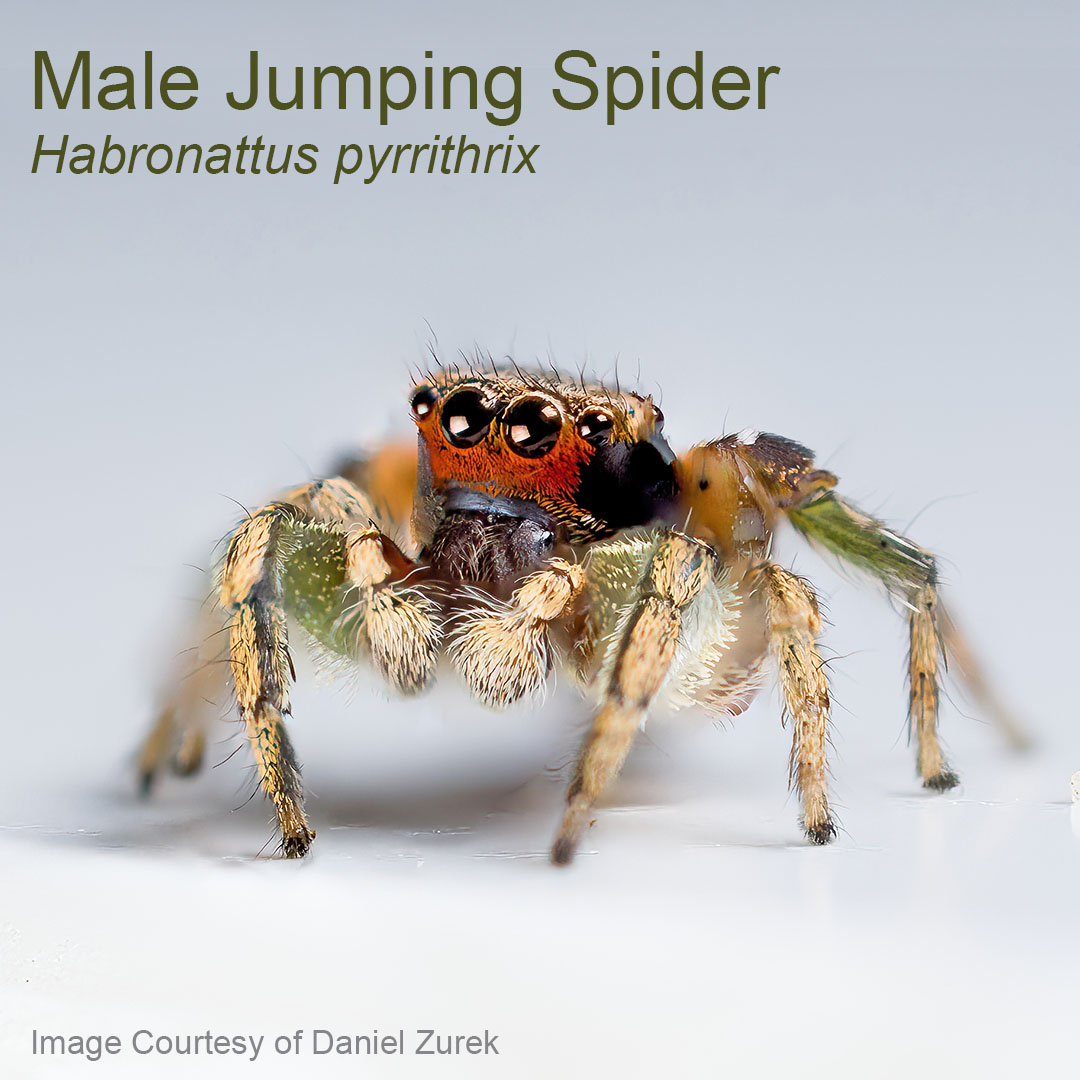

So, when you're talking about this complexity, I suspect you've gravitated into your jumping spiders because they're the ones that have these amazing dances and displays. If someone has not looked up jumping spiders and they are exquisite, I mean, they're like little jewels, actually, I would say. Are there particular jumping spiders, because there are so many of them, are there a particular species that you really like?

Nate:

So, we've been studying the peacock jumping spiders from Australia. That's a great one to search for on YouTube, but we actually have a group in North America that are just as charismatic that we've begun calling the Paradise Jumping Spiders. They're in a group of jumping spiders in the genus Hibernate and they're probably in many of your North American listener's backyards. They're really quite ubiquitous. They have bright colors. They have really flamboyant courtship displays. And so, we're studying those two groups, among others, to try to understand these questions about complexity and signaling and attention.

So, we've been studying the peacock jumping spiders from Australia. That's a great one to search for on YouTube, but we actually have a group in North America that are just as charismatic that we've begun calling the Paradise Jumping Spiders. They're in a group of jumping spiders in the genus Hibernate and they're probably in many of your North American listener's backyards. They're really quite ubiquitous. They have bright colors. They have really flamboyant courtship displays. And so, we're studying those two groups, among others, to try to understand these questions about complexity and signaling and attention.

Dr. Biology:

So, I have a scientist that's working on vision. I have a scientist working on sound.

Kim:

Mm hmm.

Dr. Biology:

Let's get back to the movement now. Nate was alluding to the fact that vision wasn't just all by itself. It's because they have to be moving through the environments as well. I suppose we're going to have the same thing going on with our frogs, right?

Kim:

Yeah. I think what really we connected with right away was that while my frogs displays might be simpler in some respects, in a frog pond at the same moment in time, there are 100 to 700 frogs calling all around. So, the environment is very complex, even if the one individual caller is making a quite simple call. And so, the task for the listener is to listen to the same animal, identify which animal they're listening to, cue in on it, pay attention. In the midst of this very complex sound environment.

Dr. Biology:

Very cluttered and so filled. It reminds me that back in World War II, they had some people that were very good at if they were in a room and there was a whole bunch of conversations going on, they could actually focus on just one conversation and listen to that one. Most of us can't do that.

Kim:

Right.

Dr. Biology:

Very difficult to do that. And so, they were pulling them out because they needed people that could listen to radio chatter.

Nate:

Mm hmm.

Dr. Biology:

Because there was so much chatter, and they could actually pull out one particular person that was on the radio there so that they could get that communication. It was just amazing to me. So, humans are always trying to catch up to the animals.

Kim:

I suspect female frogs are much better than we are at this. [Laughter]

Nate:

So, what you've just mentioned is an attentional process. It's the ability to focus attention on one thing and exclude the other types of information and that's part of this. Absolutely. The other is just where you are. So, let's take this conference environment here at the poster sessions or at the coffee breaks. There's 101 conversations going on in which conversation you can hear and understand has just as much to do with where you are in that room. Right?

Where that frog is at that frog pond determines what she hears and who she's close to is going to be what she's going to be mostly able to take in. So, where animals are in their environment is critical, but it's not something that people have historically spent as much time. At least we don't think they've spent as much time as they should have paying attention to where everybody is when all of this is happening. And without that information, we can make assumptions about, oh, well, she's hearing that male singing away just fine. But if she's not in the right spot, she might not hear him very well, if at all.

Dr. Biology:

Right.

Nate:

So, these questions about where in the room, where in the environment, where at the frog pond individuals are, is critical for understanding how well communication works. Who's listening to who, what messages are getting across. And it's something that we're trying to highlight as being a really exciting and interesting but understudied area in biology.

Dr. Biology:

Is there a pivotal moment that you had out of this conference? An aha moment that it's like. Great. I've got to get back to the lab because that was so cool. I've got to try that.

Nate:

So, one thing that I have really taken away, especially from this conference, is there's a difference between description of where an animal is and how it's moving and the meaning behind that. So, when we think about animal movements, for example, in displays, if you've got a courting male it's now easier and easier to track where each of his body parts are during that. But then taking that pattern of movements and understanding that that has some symbolic meaning to it, that this is this thing where he's communicating this message.

We've learned that from dance because there are symbolic representations used to characterize human dance performances, such as labanotation, that can then be paired with this much more descriptive set of where is the wrist, where is the knee? And pairing those two together not only gives the dynamics and the description, but also the meaning. And I think oftentimes as scientists, we're trying to understand the meaning of what animals are doing. But it's a lot harder to get answers to that because, of course, you can't interview them and ask them, what are you trying to do?

So, we have to take other routes to understanding the meaning. I have an artist friend who described my work as being natural semiotics and for those that don't know what semiotics is, it's the study of meanings and symbols oftentimes in the human world. And that really is actually a perfect description of what I'm up to, is trying to understand the symbols and meanings in a completely alien set of communication, which is jumping spider or butterfly communication

Dr. Biology:

All right. I think Nate might remember should from listening to the show, there are three questions I ask all my scientists Are you ready, Kim? Okay. You're going to start. OK. So, the first question, do you recall if you had an aha moment at some point in your life where you said, wow, I'm going to be a scientist, this is just too cool?

Kim:

You know, I had that aha moment essentially after I was already a scientist. I didn't know what I wanted to do. I was really interested in everything. And I remain interested in everything. And I just went to do a real-life biology experiment for my first time. And said, this is fascinating. And I heard active scientists talking about how the brain worked. And I said, oh, that's amazing. And so eventually I just went in that direction. But it wasn't a conscious I will be a scientist. It was I find myself becoming a scientist.

Dr. Biology:

Well, it's not uncommon

Kim:

Mm hmm.

Dr. Biology:

When I was in elementary school, they had a publication called The Weekly Reader.

Kim:

I remember that.

Dr. Biology:

And I can still see the photograph in my mind of this guy in a white coat, lab coat, in front of this amazing giant instrument. That was a microscope. It was an electron microscope. [Laughter] And I thought that was so cool. Okay, that's elementary school. Fast forward. I am a passionate artist. My undergraduate degree I get my degree in fine arts. I do, you know, tons of interactive things. I do dance performances off of some of the things we've done. One thing leads to another, and I end up going back in the sciences, and the next thing I want to do is I'm taking a class in electron microscopes, and I'm sitting at a sitting in this dark room in front of this electron microscope. And I'd forgotten completely about that Weekly Reader.

Kim:

Was it as romantic as you envisioned it when you were in elementary school?

Dr. Biology:

You know, it was interesting because I typically did a lot of the scope time in the afternoon after lunch in it's in the subbasement. It's cool and it's dark and I would feel like I was going to nod off sometimes. [Laughter] But as you're looking at that screen and you're looking at those specimens, you're often looking at things that no one's ever seen before. You're there for the first time. So, I'm not an astronaut. I'm a micronaut. I study inner space rather than outer space.

Nate:

Well, it really is an alien landscape when you start looking at things at a scale that we're not used to. And it's beautiful. The microscopic world is full of beauty.

Dr. Biology:

And it's infinite.

Nate:

Yeah,

Dr. Biology:

We can go out into the cosmos, but I guarantee you, we can go shrink and down forever. [Laughter] As one of my guests you know, I had Stuart Lindsey on who deals with atomic force microscopes, and we were talking about the nanoworld. And he says things get really kind of weird.

Nate:

Oh, yeah. Wow. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. It becomes probabilistic in ways that we don't really.

Dr. Biology:

Well, even Ant-Man, they try to talk about you kind of get that.

Nate:

Yeah. Yeah.

Dr. Biology:

Ant-Man and the Wasp or something.

Nate:

Yeah. Yeah.

Dr. Biology:

OK, so Nate what about you? Did you have a point where you said, yeah, I'm going to be a biologist?

Nate:

I'm one of those obnoxious people where that decision seems to have happened even before my earliest memories. There are stories of me coming to the back door, having caught bumblebees and flowers in the backyard, and I get stung, you know, by the bumble bee just to show it to my mother. So, I've always thrilled to the world of small things. Part of it probably comes from me growing up in an inner-city neighborhood in Rochester, New York, where there were few things as variable and fascinating as the bugs in the backyard. So, from the age of three or four, I've been fascinated by insects and spiders and yeah, just have had the good fortune to continue that childhood fascination into adulthood.

Dr. Biology:

Right. So, now I'm going to be a bit mean.

Nate:

Sure. [Laughter]

Dr. Biology:

I'm going to take it all away. You don't get to be a scientist. [Laughter] And almost all my scientists that have been in the university and teach, they love teaching. So I take that away because what I want to know is if you couldn't do those things, if you weren't doing those things, what would you do or what would you be?

Nate:

This isn't actually a very difficult question for me because I've imagined my way into many other ways of being in the world. The most recent Plan-B, if you will, was to go into the spice trade. I have a passion for cooking, and I'm also a synesthete, which means that for me, smells and tastes are represented in my mind as very distinct, vivid colors, sensations. So, I love to cook. It's a painterly experience for me. And there's also a rich history associated sometimes a dark history, sometimes an amazing history associated with spices and the world of spices. So, I thought very seriously about starting a business associated with spice-trading and educating people about spices and cuisines around the world, associated with spice.

Dr. Biology:

Oh, yes. I mean, there have been spices that have been worth their weight in gold over the period of time. Yeah, absolutely. All right, Kim, you got a little bit of a head start there.

Kim:

Yeah.

Dr. Biology:

To think it through because I'm taking it all away.

Kim:

Well, it's tough because unfortunately, I also love cooking. Before I got my job as a professor, I wasn't sure what my future was going to hold, but I knew I was going to find something I was really excited about doing. And I thought having a small cafe of the right type where I was cooking and creating food for other people, to experience would really make me happy. So, I thought, no matter what happens with my career, I'm going to find something beautiful to do. And food seems like a great thing to share with others.

Dr. Biology:

So a chef.

Kim:

Of a small scale, not a Top Chef.

Dr. Biology:

Yeah, well, small scale can still be a Top Chef.

Kim:

True.

Nate:

Just to share a little bit more about the human side of all of this. We both talked about our enjoyment of cooking and one of the things that we're going to do after this conference is go off and cook together for this group up at Arcosanti. And that's the part of the human side of things is being in community together and learning from each other, but also meeting each other and our shared humanity. So, it's really fun to find common ground scientifically. But also, personally and I'm really looking forward to that part of things as well.

Kim:

And I will say that that is one of the secrets to what brought our group together. It wasn't only that we had shared scientific interests. We made each other laugh and enjoyed time together, even if we weren't in the same place.

Dr. Biology:

Right. All right. Last question. What advice would you have for the young Kim growing up that doesn't know what she wants to do yet, but thinks she wants to be a scientist?

Kim:

I think the same thing is true for young Kim and a young Nate, which is keep your curiosity, keep asking questions, keep dreaming and looking at small things and big things. And really enjoying them to their fullest. And that will lead you to asking and answering questions. And then you're automatically a scientist even if you don't have the formal training, which can come later.

Dr. Biology:

And even if you don't become a scientist. My feeling is everybody's a scientist, right?

Kim:

Right.

Dr. Biology:

They just may not have come out of the closet yet. [Laughter]

Dr. Biology:

Nate, what about you? What advice?

Nate:

I think it's important to pay attention to what you thrill to. What really brings you alive in life and follow that. You know, oftentimes we hear follow your dreams or follow your passions. But I really think that society works best if we all do what we're good at. And so I think people should really pay attention to what excites them the most and then develop that in a purposeful way. There have been times in my life where I have tried to meet the expectations of others, even when they were not things I was passionate about. And those, I think, were lost moments sometimes for me. And coming back to what passions really drive me has been a powerful thing for me over and over again. Any time I get lost, if I return to my passions, that it steers me true.

Dr. Biology:

On that note. I want to thank you both for taking time out to be on Ask A Biologist. Thank you, Kim:

Kim:

Thank you.

Dr. Biology:

Nate.

Nate:

Thanks, Dr. Biology. Great to be back and looking forward to continuing to hear your program in the years ahead.

Dr. Biology:

You have been listening to Ask a biologist, and my guests have been Kim Hoke, an associate professor in the Department of Biology at Colorado State University. And we also had Nate Morehouse, an associate professor in the Department of Biological Sciences and the director of the Institute for Research in Sensing at the University of Cincinnati. And before you go, remember to check out the chapter links and show notes for more information about Kim's and Nate's research animals, which brings us back to the riddle at the beginning of the show. What's the favorite game for a butterfly, a jumping spider, and a frog? And who usually wins? The answer, you probably figured it out, is leapfrog. And the winner is usually the butterfly, but it has to wing it to win.

[La la, la, la – sound effect]

Dr. Biology:

The Ask a Biologist podcast is usually produced on the campus of Arizona State University and is recorded in the Grass Roots Studio, housed in the School of Life Sciences, which is an academic unit of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences But for this show, we're at the annual Research Conference for the Society of Integrative and Comparative Biology.

Dr. Biology:

And remember, even though our program is not broadcast live, you can still send us your questions about biology using our companion Web site. The address askabiologist.asu.edu or you can just Google the words ask a biologist. As always, I'm Dr. Biology, and I hope you're staying safe and healthy.

Bibliographic details:

- Article: What’s Been Cooking at SICB?

- Author(s): Dr. Biology

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/listen-watch/whats-been-cooking-sicb

APA Style

Dr. Biology. (). What’s Been Cooking at SICB?. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/listen-watch/whats-been-cooking-sicb

Chicago Manual of Style

Dr. Biology. "What’s Been Cooking at SICB?". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/listen-watch/whats-been-cooking-sicb

Dr. Biology. "What’s Been Cooking at SICB?". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/listen-watch/whats-been-cooking-sicb

MLA 2017 Style

The courtship between female (left) and male (right) jumping spiders (Habronattus pyrrithrix) is a colorful dance display that many people miss seeing because these animals are so tiny. Image Courtesy of Colin Hutton

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.