The coral animal

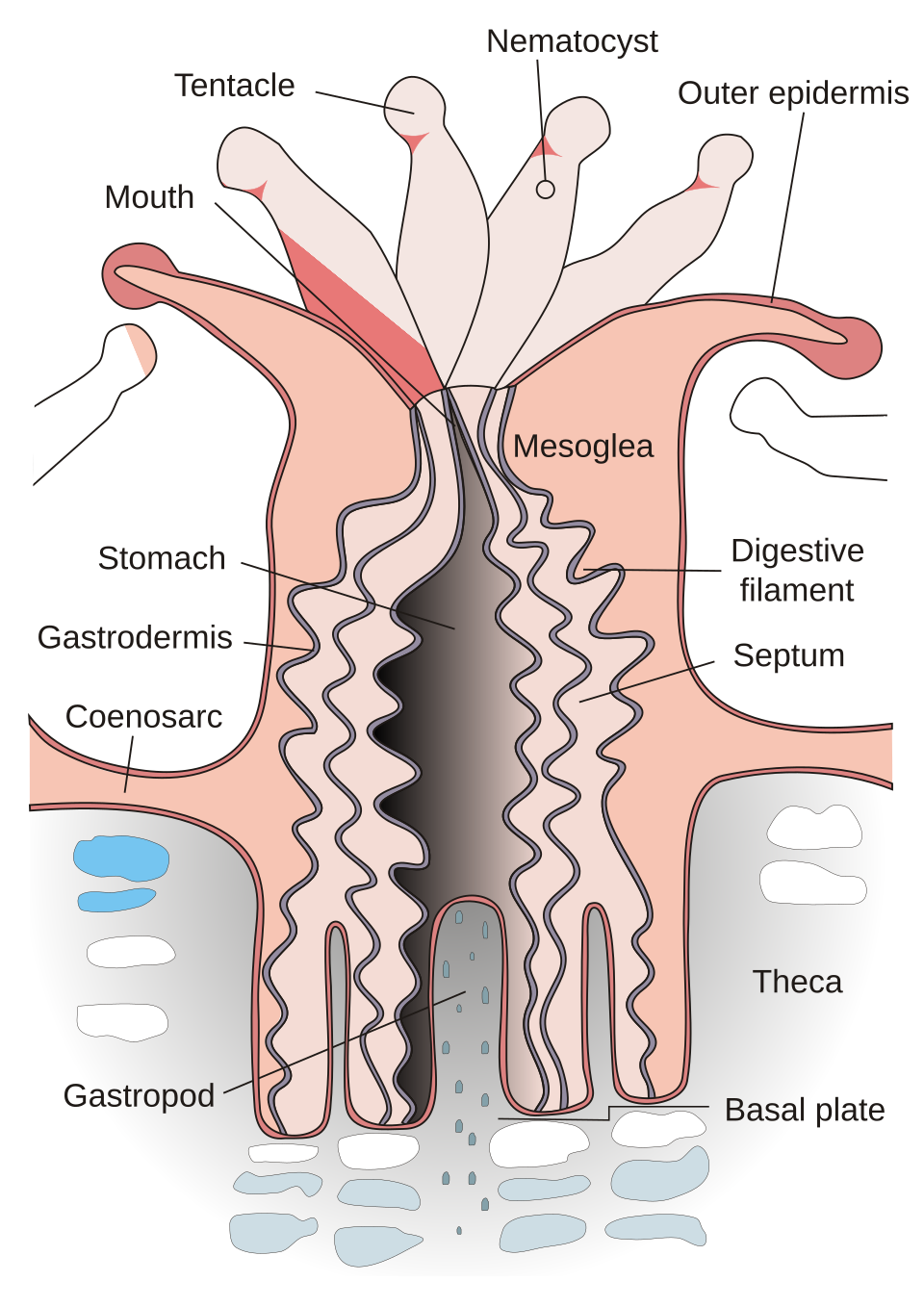

If you’ve seen a jellyfish or a sea anemone, then you may be more familiar with coral polyps than you think. Their structures are very similar. Polyps are mainly just a stomach.

Most of what we can see is the polyp’s mouth. When not contracted, it is surrounded by tentacles. They use these to catch food and to defend themselves. Their tentacles have nematocysts, making them like tiny venomous stingers. All the polyps are attached to a hard surface, one they each helped to create.

Coral polyps come in various sizes. Some choose to live alone on the reef as a large solitary polyp much like a sea anemone. Others grow in colonies of hundreds to thousands of smaller polyps.

The hard stuff

Corals often get misidentified as rocks… and that’s not too surprising. Coral polyps mix carbon dioxide with calcium in the water to build a calcium carbonate base. Calcium carbonate is also known as limestone (a rock!). All the polyps in a coral colony grow outward from this base, adding more limestone to fill in the gaps. This base forms the colony’s skeleton.

It takes corals quite some time to build their skeletons. They grow only a few centimeters each year. But they also shield the reef and the coastline from ocean storms. Corals can absorb a lot of the energy from waves that crash against them. This can sometimes cause small bits of coral to break off. Some types of corals can then grow new colonies from these broken pieces. This process is called fragmentation.

Partnering up

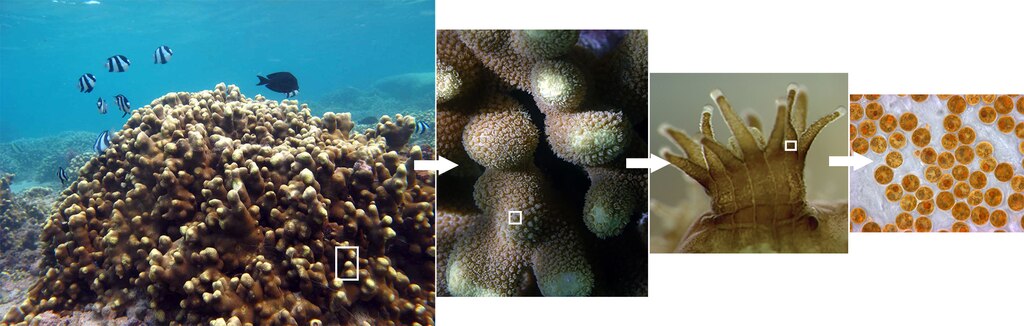

The true magic of every coral reef hides within every coral polyp. In their tissue they house a special resident. An algae called zooxanthellae that lives in symbiosis with their host. These little photosynthesizers provide most of the energy needed for their coral partner. In return the coral gives them nutrients and a safe place to live.

For this partnership to last conditions need to be just right. Waters shallower than 30 meters (~100 ft) provide the perfect setting for tropical corals and their partners. Yet, big changes in temperature, light, or pollution can stress their relationship. This can cause corals to kick out their algae. Without these partners, corals lose their color and turn pale white, which is called coral bleaching. If they stay apart too long, the coral could die from starvation.

Get in the zone

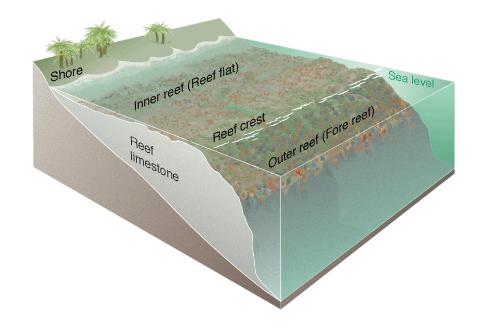

From the outside it may seem that a reef is all the same. But neighborhoods exist just like any other city. These are known as reef zones. Every zone has unique conditions making it suitable for only certain types of organisms.

From the shore, you are likely to first enter a reef flat. For marine creatures this is a tough place to live. The temperature, light, and saltiness of the water here changes often. Only the hardiest of organisms call this neighborhood home. Further in is the highest point of a reef, called the reef crest. This zone gets the most sunlight, but it also gets hit by the strongest waves. Be careful not to get swept away!

Continuing toward the sea, the reef starts to slope downward into deeper water. These sloping neighborhoods are called the fore reef. Here, sunlight quickly becomes scarce. You will also find the most diverse reef communities. This zone is well-protected and has a gradient of light. Different species have adapted here to live at specific depths.

Read more about: Cruising Around Coral Reefs

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Anatomy of a coral reef

- Author(s): Dr. Biology

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/anatomy-coral-reef

APA Style

Dr. Biology. (). Anatomy of a coral reef. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/anatomy-coral-reef

Chicago Manual of Style

Dr. Biology. "Anatomy of a coral reef". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/anatomy-coral-reef

Dr. Biology. "Anatomy of a coral reef". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/anatomy-coral-reef

MLA 2017 Style

The colors of coral come from their symbiotic partners, an algae called zooxanthella.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.