Down the Drain: Hospital Sewage and Antibiotic Resistance

What's in the Story?

The next time you go to the hospital, take note of how clean it is. As you walk toward the reception desk, you might inhale notes of bleach and air freshener as your shoes squeak upon newly polished tile. As you travel further through sterile hallways, past equipment and medical tools wrapped in plastic, you see hand sanitizer on every table and desk. You peer inside a room to watch a doctor wash his hands as he says goodbye to his patient. You feel comfortable knowing that any lurking germs and the antibiotics used to treat them will soon be sent away...but where do they go?

In the Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health article, “Vancomycin gene selection in the microbiome of urban Rattus norvegicus from hospital environment,” scientists examine a surprising destination for particularly threatening hospital-borne germs, and discuss the implications it has for public health.

As it turns out, certain strains of bacteria have also evolved a resistance to vancomycin, the antibiotic used by our doctor above. This is where our story takes a smelly turn.

Trouble in the Sewers

Throughout the day most people in the hospital will use the bathroom for one reason or another. Although hospitals are very clean, the pipes and sewers beneath them are not. It has already been shown that hospital wastewater is teeming with both antibiotics and antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Knowing this, researchers in Denmark set out to determine if the rats (Rattus norvegicus) that live in the sewers around a hospital are carrying extremely dangerous antibiotic-resistant bacteria within their guts (the gut provides a bacteria-friendly environment).

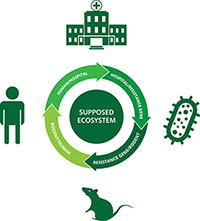

When another species hosts bacteria that affects humans, that species is called a “reservoir” because even if we treat the bacteria in humans, they provide a source from which the bacteria can keep spreading into the human population. Using this idea, the researchers thought that rats near hospitals might be a reservoir for antibiotic-resistant bacteria. They predicted that there would be more antibiotic-resistant bacteria within the guts of rats that live around hospitals than rats that live elsewhere.

Digging for DNA

To test this hypothesis, the researchers collected the fecal matter of rats (I told you it would get smelly) in urban areas of Malaysia, Hong Kong, and Denmark. Apparently, rat fecal matter is easy to identify (who knew?). The research team ran some of the rat feces through some tests to make sure it was from the correct species. Their next step was to sequence the DNA of the bacteria living inside of the rat feces, so that they could see if it is similar to the DNA of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

To do this, they froze the feces to preserve the DNA of any life forms living in it. Next, the researchers separated the DNA material from the waste so that they could sequence the DNA. The first step of DNA sequencing is to chop up the DNA into small fragments. Next, these fragments are duplicated many times, so that there are thousands of copies of each fragment. Last, dyes are added to the DNA fragments that “tag” each nucleotide with a different color. Once all of these steps are complete, the DNA fragments are fed through a machine, which reads the DNA sequences and reconstructs the DNA present in the rat feces.

Positive Results, Frightening Implications

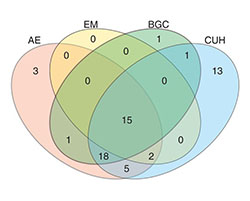

I have bad news, and I have worse news. In all of the rat feces tested, researchers found genes linked to antibiotic resistance. Even worse, rats that live in the vicinity of the hospital have way more of these antibiotic-resistant bacterial genes in their feces than the other rats.

These bacteria likely were able to thrive within the rat gut for two reasons:

1) Antibiotics in the hospital sewer water could have created an environment where only strong bacteria can survive. If the bacteria that live inside the rats are always exposed to new antibiotics, only those bacteria that have a high resistance will survive and reproduce. This would create an environment of extremely strong bacteria that may be resistant to several antibiotics.

2) Bacteria have the ability to “give” some of their DNA to other bacteria. This is called “horizontal gene transfer”, and is actually the most common way antibiotic resistance is spread among bacteria. So if antibiotic-resistant bacteria were flushed down a hospital toilet, they could have given their genes to other bacteria that can more easily infect the guts of rats.

Although the sites of this study only included one specific hospital area (in Denmark), the results suggest that the waste that comes from hospitals may be affecting the bacterial reservoirs living in the sewers.

Antibiotic-resistant Bacteria and Human Health

While this study focuses on a very specific location, it is the first of its kind to suggest that antibiotic-resistant bacteria are being transmitted between humans and animals via sewage. The researchers who conducted this study did not explore whether rats can spread the bacteria back to humans, but other studies suggest this might be able to occur, and it is part of the proposed transmission cycle here.

In addition, they made it clear that if antibiotic-resistance in bacteria is being strengthened by hospital waste, it is extremely important to investigate this cycle on a global scale. On that, I think we can all agree.

EvMed Edits are sponsored by ASU's Center for Evolution and Medicine.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons.

Read more about: Down the Drain: Hospital Sewage and Antibiotic Resistance

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Down the Drain: Hospital Sewage and Antibiotic Resistance

- Author(s): Tyler Quigley

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/evmed-edit/hospital-antibiotic-resistance

APA Style

Tyler Quigley. (). Down the Drain: Hospital Sewage and Antibiotic Resistance. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/evmed-edit/hospital-antibiotic-resistance

Chicago Manual of Style

Tyler Quigley. "Down the Drain: Hospital Sewage and Antibiotic Resistance". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/evmed-edit/hospital-antibiotic-resistance

Tyler Quigley. "Down the Drain: Hospital Sewage and Antibiotic Resistance". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/evmed-edit/hospital-antibiotic-resistance

MLA 2017 Style

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.