Are bird numbers declining?

Submitted by

MicheleGrade level

11Answered by

David PearsonAre birds disappearing?

Go outside during the day and listen. Do you hear any birds calling? Depending on where you are, you may hear a few. But just 40 years ago, if you were somewhere in North America, you probably would have heard at least three times as many. Since then, we have lost about a third of our birds. Across the world, many countries are experiencing a loss in bird numbers. Does that mean all bird species have dropped in numbers? No. But such a change in number should still make us worry.

Are some types of birds in more danger than others?

Yes, the numbers of birds like Meadowlarks that live in grasslands and Yellow-headed blackbirds that live in marshes have dropped the most. Numbers of birds like Hairy Woodpeckers that live in forests and Long-billed Dowitchers that live mainly along the coast are down, too, but not as much. Desert birds like Cactus Wrens are down in number as well, but we also know that there are exceptions. Some desert birds like Curve-billed Thrasher, Verdin and Gila Woodpecker have been able to move into parts of cities where there are parks and trees around homes. Their numbers may actually be increasing. Birds that live in the water like ducks and geese are also increasing. So are many types of hawks and eagles.

Top ten most endangered and rarest bird species

Which birds are most at risk? Here are the top ten most endangered and rarest bird species in the continental US; these species have also experienced declines in the last 40 years:

- California Condor

- Whooping Crane

- Gunnison Sage Grouse

- Kirtland's Warbler

- Piping Plover

- Florida Scub-Jay

- Golden-cheeked Warbler

- Ashy Storm-Petrel

- Kittlitz's Murellet

- Lesser Prairie Chicken

Is there hope for the future of our birds?

The decrease in bird numbers is a warning to us that something is wrong. But because some species in some habitats are doing OK or are even increasing, there is hope. We don’t know all the reasons for the bird numbers going down so fast, but we are trying to find out. In the meantime, it is important that we protect our habitats to make sure there is room for birds to spend the winter, to nest in the summer, or to pass through safely when migrating. These few items are the best way to stop the numbers of birds from going down.

How do we measure these bird numbers?

You might also wonder how we count all the birds. We have two ways of finding out about this sharp drop in numbers. For more than a century, birdwatchers have written down how many birds and how many species they see at certain times of the year. For several decades, those numbers have been given to the Audubon Society to add up the total number of bird species. This is part of how we know what bird numbers have been doing.

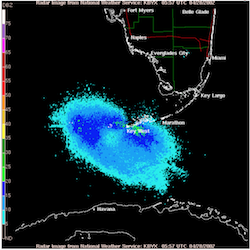

In addition, many years ago new types of radar stations around airports started seeing strange “clouds” being picked up on their screens at night when there were no airplanes or clouds around. It turned out that these clouds were large flocks of migrating birds. They probably fly at night to avoid hawks and other dangers. The individual dots that make up these clouds on the radar screens can be counted. Then, the total number of all the birds in each cloud can be compared to pictures of radar clouds from past years. This comparison shows how bird numbers have changed over time. Having two very different ways of measuring the number of birds is more reliable than having only one counting method.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Birds on a wire by Tomascastelazo.

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Are bird numbers declining?

- Author(s): David Pearson

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/questions/are-birds-declining

APA Style

David Pearson. (). Are bird numbers declining?. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/questions/are-birds-declining

Chicago Manual of Style

David Pearson. "Are bird numbers declining?". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/questions/are-birds-declining

David Pearson. "Are bird numbers declining?". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/questions/are-birds-declining

MLA 2017 Style

In North America, we've lost nearly a third of our birds in the last 40 years. Which birds are in danger and is there still hope for the future of our birds?

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.