Natural Resistance

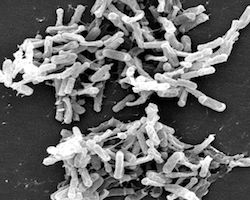

Clostridium difficile under a high-powered microscope. This bacteria is naturally resistant to many antibiotics, and causes people to have very bad diarrhea. Image by the CDC.

Some bacteria are naturally equipped with defenses against antibiotics. One defense that some bacteria have is a chemical that destroys the antibiotic molecule. When the antibiotic is near the bacteria, they release their chemical defense, which causes the antibiotic to stop working. Another way they defend themselves is by changing some of their own proteins so that the antibiotic cannot touch the outside of their cell bodies. For instance, many antibiotics try to latch onto a bacteria’s receptors, molecules that sit on the outside of bacteria and receive signals. Some of these bacteria can change the shape of their receptors, so that the antibiotic can’t bind to it. If it can’t bind, it can’t kill it.

There is a very common antibiotic-resistant bacteria species called Clostridium difficile that causes people to have bad diarrhea. C. diff uses both chemical and shape-changing defenses, and tends to thrive in people who are taking antibiotics for other bacteria.

Genetic Mutation

Sometimes, when a bacterium is multiplying, a random mistake in the bacterium’s DNA will create a gene that gives it resistance to antibiotics. Every time a multiplication event happens, there is a chance a mutation can occur. Because bacteria multiply A LOT, there is a higher chance a mutation like this will occur.

One bacteria species in which this happened is Vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE), a strain of bacteria that is resistant to an antibiotic called vancomycin. VRE have been around for over thirty years, and they are very well studied. In fact, scientists have been able to group different strains of VRE according to how they defend themselves against vancomycin. For two types, called VanA and VanB, the bacteria gained resistance when a mutation occurred in their DNA. This mutation gave the bacteria an ability to fend off the vancomycin molecule.

Horizontal Gene Transfer

Some bacteria acquire resistance when they are “given” a gene by another bacterium through a process called horizontal gene transfer (HGT). There are three ways that HGT can occur.

- Transduction – This occurs when a virus attacks a bacterium and steals some of its DNA. This virus can then attack another bacterium, and drop off the genes it took.

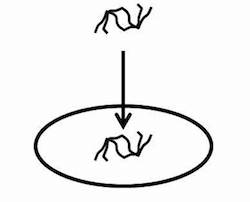

- Transformation – Sometimes, there are genes floating around in a bacterium’s environment. The bacterium can absorb these genes and add them to their own DNA.

- Conjugation – Two bacteria can trade genes by briefly fusing to one another, and sending genes to one another through the connection.

The genes that a bacterium gains through HGT are not always ‘resistance’ genes, but when they are, it greatly increases the risk of antibiotic-resistant bacteria spreading throughout our population.

A dangerous, but also very widespread, bacteria called Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) is known for its ability to spread ‘resistance’ genes through HGT. CRE can cause infections in our bloodstream, wounds, and urinary tract, and are one of the hardest bacteria to kill, because they can survive almost all antibiotics.

Read more about: Antibiotics vs Bacteria: An Evolutionary Battle

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Antibiotic Resistance

- Author(s): Dr. Biology

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/antibiotic-resistance

APA Style

Dr. Biology. (). Antibiotic Resistance. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/antibiotic-resistance

Chicago Manual of Style

Dr. Biology. "Antibiotic Resistance". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/antibiotic-resistance

Dr. Biology. "Antibiotic Resistance". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/antibiotic-resistance

MLA 2017 Style

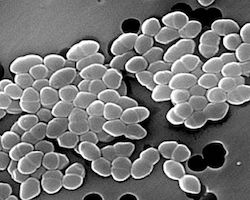

Some bacteria form pili, hair-like appendages shown in a bundle here, that enable them to do well in certain parts of the body of their hosts, or to trade genes with other bacteria.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.