Illustrated by: David Kiersh

The Different Cells of Our Bodies

Let's take a journey through the body. If you shrunk down to the size of a cell and were transported into the body, how might you tell where exactly you landed? Well, one way could be to look for specific types of cells. Humans have around 200 different kinds of cells. Let's look at two as an example: brain cells and blood cells.

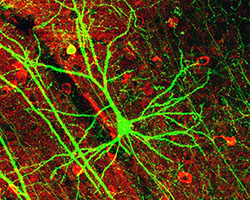

The brain is the main manager of our body. It receives and processes information from the environment and it tells the other organs what to do – for example it orders our muscles to contract, so that we can move. To send these orders, the brain cells need to transmit electric or chemical signals to the cells of the specific muscles. These signals sometimes have to travel very long distances. To accomplish this task, a brain cell – also called nerve cell – develops a specific structure. This cell type has long branches off the main cell body that can reach a length of up to one meter. The unique structure of nerve cells enables them to pass on signals from the brain in our head to muscles as far away as our little finger in a very short amount of time.

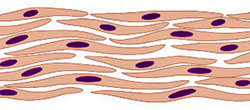

Next let's travel into our vessels and visit another cell type: the hard working red blood cell. Red blood cells move oxygen from our lungs to other organs so that they can keep working. These tiny cells are able to move around our whole body very fast - within 20 seconds. To move around the body quickly, a structure like that of nerve cells wouldn't work well. Long nerve cells might get tangled or move too slowly in the blood stream. Blood cells are a lot smaller than nerve cells and have a disc-shaped structure, both great traits for moving quickly through small spaces. Their disc shape also provides them with a big surface where lots of oxygen can enter the cell.

From this comparison you can see that the structures and functions of cells can vary depending on the different organs in which they are found. How do our bodies create such a wide variety of cells? And how do they do such different jobs?

Different Proteins

No matter what type of cell you think of, it is built in part by proteins. Proteins are large molecules that not only form important parts of your body, but also do important work. Just like there are different cell types, we also have various kinds of proteins that have different functions. Some are only used to build the structures of a cell, others perform specific tasks. Red blood cells carry a specific type of protein, called hemoglobin, which is able to bind oxygen and release it in other tissues. A nerve cell doesn't have this protein because it doesn't need to bind oxygen. Instead, the nerve cell uses other proteins that help it transmit signals to other cells. Many of the differences between cells come down to this main idea: different cells produce different proteins.

Protein Production

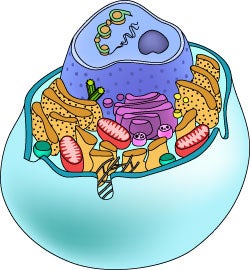

Different types of cells can produce all of the same proteins. How is that possible? Most cell types have some basic structures in common: The heart of a cell is the nucleus that contains the DNA. DNA is a very important molecule – maybe the most important molecule for life on Earth. DNA forms the genetic code which holds the instructions to create all of the body's cells.

A gene is a small segment of DNA that is used by a cell to produce a specific protein. All our cells contain the same copy of DNA with around 25,000 genes coding for 25,000 different proteins. But wait a second. Maybe you notice the problem with this concept: cells don't all produce the same proteins, because different cells do different jobs. If all cells contain the same DNA, how can a blood cell produce different proteins than a nerve cell? Shouldn't all cells contain the same proteins and therefore function in the same way?

Silencing Genes

To overcome this problem, cells use a very smart control mechanism to make sure that only the necessary genes on DNA are used. Those "necessary" genes can vary from cell type to cell type. You can compare cell development to baking a chocolate muffin versus a blueberry muffin: some ingredients like eggs, flour and milk are the same in every muffin but each type of muffin requires special additional ingredients like chocolate or blueberries leading to the specific taste. That's basically what's happening in the nucleus: the recipe on the DNA contains a list of the ingredients for creating all possible cell types. When a cell grows and develops it decides which ingredients are needed to build the specific cell type and only reads those respective parts of the recipe.

While muffins are made with milk, eggs, and flour, the ingredients to build a cell are proteins. Some proteins are the same in most cells: muscle cells and nerve cells need to build common structures like mitochondria. But there are also unique ingredients in both cell types: a muscle cell needs special proteins that let the muscle cells move during contraction. These are called myosin and actin. So a developing muscle cell has to read the respective genes to produce myosin and actin out of the recipe. A cell that develops into a nerve cell doesn't need myosin or actin and so it will inactivate these genes. In exchange it will read genes for the proteins that enable transmitting signals to other cells.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Tissue image of parotid gland via Wbensmith.

Read more about: Controlling Genes

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Controlling Genes

- Author(s): Katharina Petsche

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/gene-expression

APA Style

Katharina Petsche. (). Controlling Genes. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/gene-expression

Chicago Manual of Style

Katharina Petsche. "Controlling Genes". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/gene-expression

Katharina Petsche. "Controlling Genes". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/gene-expression

MLA 2017 Style

We have around 200 different cell types in our bodies, but all are made from the same set of instructions.

Want to know more about the basics of DNA? Visit our story DNA ABCs.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.