Local Fly Food Secrets

What’s in the Story?

If you asked all your friends about their favorite foods, someone would likely say pizza. Pizza has been an American favorite since its introduction from Italy. Unique pizza styles are often named after the region where they are popular.

Classic New York style pizza has an unbelievably thin crust. New Yorkers often fold the floppy slice in half and eat it crust-side-out. A thin, folded New York slice is quite different from an oozing deep-dish Chicago slice. These monstrous pizzas have the thickest crusts of all. Sometimes people use a fork and knife to help them wrestle through a slice of deep-dish Chicago style pizza.

Within the United States, people’s pizza preferences are often influenced by where they live. But location-based food preferences are not unique to humans. Researchers are finding that the food preferences of some animals can be based on where they live, too. In the PLOS ONE article “Host Plant Adaptation in Drosophila mettleri Populations” scientists studied the plant preferences of different populations of a fly species. They wanted to find out if any of these flies are very different from the others. If they are, these flies may eventually go on to form a new species.

Sonoran Desert Flies

Although many different fly species live in the Sonoran Desert, people often call Drosophila mettleri the Sonoran Desert fly. In this desert, this species of Sonoran Desert fly eats and nests near the local tall, columnar cacti. The flies lay their eggs in the soil beneath these host plants. As the cactus ages and its tissues decay, it leaks juices into the surrounding soil. This cactus juice provides the flies with all the nutrients they need to survive.

"Local" Flies?

A local adaptation is a unique trait that only some members of a species have. Populations sometimes gain an ability that helps them to survive in their local environment. This could mean eating a different food, waking up at a different time, or being a different color than the rest of the species. Locally adapted populations are well-suited to their environments, where they may survive better than the rest of the species. Is local adaptation happening in the Sonoran Desert fly? That’s what researchers wanted to find out.

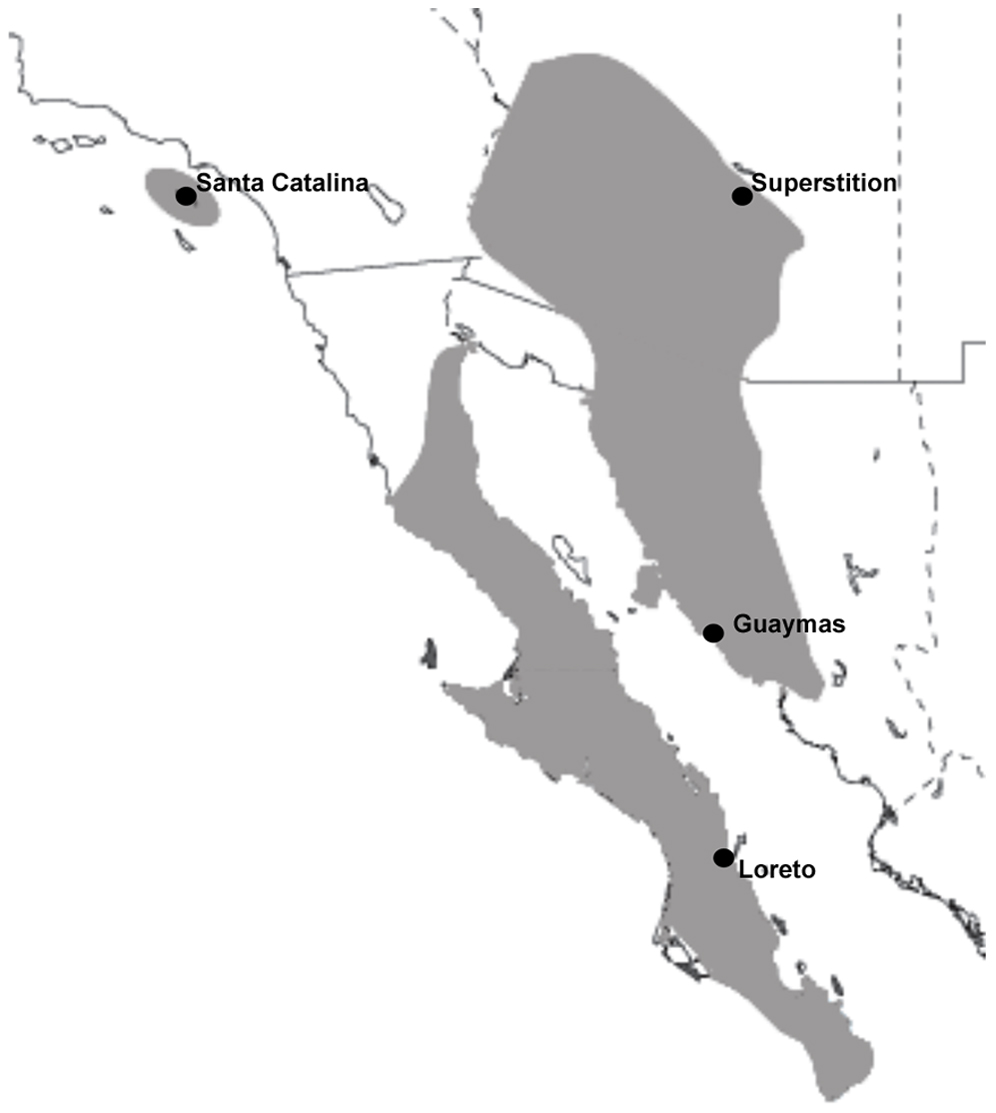

Scientists took to the deserts of Arizona, northern Mexico, and southern California armed with mesh nets and glass cages. Spreading over the dusty landscape, swinging nets, researchers captured these tiny Sonoran Desert flies. Flies were collected from four physically separated, or allopatric, populations. The researchers also collected samples of the flies’ host plants from each area.

Studying Host Plants

Prior studies showed which host plants the flies preferred. The saguaro and cardon cacti are the two main hosts of the Sonoran Desert fly. But these flies are also known to feed on other types of cacti, including several prickly pear species. Each host plant’s composition was investigated to see if it contained any toxic chemicals. If a plant contains toxic chemicals, it can only be eaten by animals which are adapted to tolerate those chemicals.

Saguaro and cardon both contain toxic chemicals called alkaloids. That means animals that feed on saguaro and cardon, like the Sonoran Desert fly, must be adapted to these alkaloids. Different alkaloids were detected in the three prickly pear species. Their alkaloids were novel, meaning that they had not been observed in another plant before! Researchers showed that the prickly pear species had the most unique chemicals compared to the other hosts. So, they decided to compare the flies’ preference for the classic saguaro versus the more unique prickly pear species.

Fly Performance on Different Host Foods

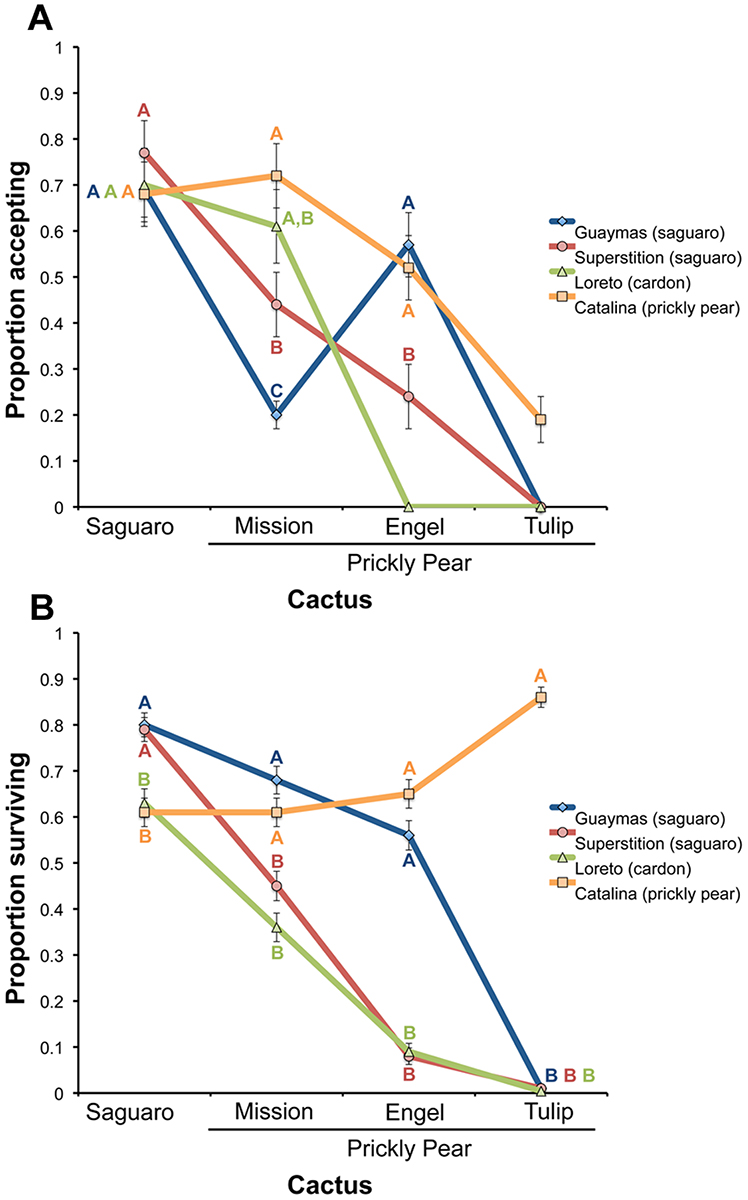

Scientists filled culture plates with sand to mimic the nests where Sonoran Desert flies lay their eggs. They first soaked the sand with cactus juice (blended cactus flesh) from one of the host plants. Researchers were interested in discovering which fly populations survived best on which host plant. To test that, female flies from each of the four populations were allowed to lay eggs on different cactus sample plates individually. Pregnant female flies from each population were each sealed inside a culture plate with the juice of one host cactus for 24 hours. Each population was tested with each cactus juice to see which host females preferred when laying eggs.

Any eggs laid in the plates were counted under a microscope and allowed to hatch. Within 12 hours of hatching, larvae were placed into glass vials in groups of 10. These vials contained sand soaked in the same cactus juice as the nest each larva emerged from. The survival of larvae on each cactus juice was used to learn each population’s performance on each host plant.

Discovering a Local Adaptation

Researchers compared the fly populations from four locations: Santa Catalina Island, the Superstition Mountains, Guaymas, and Loreto. These flies all belong to the same species and live in similar habitats. Researchers found that flies from Santa Catalina Island had a unique ability. Unlike the rest of the populations, the Santa Catalina flies performed very well with prickly pear hosts. This suggests that this population is locally adapted to grow on prickly pear.

Using saguaro as the host plant, however, the four fly populations showed similar survival rates. This means the Catalina flies are adapted to the prickly pears’ unique chemistry, but the other fly populations are not. This adaptation is unique to the Santa Catalina flies as they are separated from other Sonoran Desert fly populations. Prickly pear grows throughout much of the Sonoran Desert fly’s range, but only the Santa Catalina Island population can use it as a host.

Wanted: Diverse Species

The Santa Catalina Island flies’ unique host selection sets them apart from the rest of the species. The difference in host selection between these fly populations is an example of diversity within a species. Local adaptations like these allow populations to compete and survive in their unique habitats. Species that are more diverse are more likely to survive stressful environmental events, such as climate change, or extinctions.

For example, if the saguaro or cardon cactus populations decline, the Sonoran Desert flies would lose their primary hosts, and would have to adapt to feeding on other hosts to survive. But the Santa Catalina population is already prepared to survive this change.

This would be like if we ran out of deep-dish pizza pans and could no longer make Chicago-style pizza. People in Chicago might eat a lot less pizza. New Yorkers, however, would be less affected because they would still have their thin-slice pies. In a similar way, the Santa Catalina Island flies could likely survive a columnar cacti extinction. They could still rely on and locally adapt to different species of prickly pear as a host. Other Sonoran Desert fly populations would be more vulnerable to this environmental change.

This story on Ask A Biologist was funded in part by NSF award 1735604 as a part of Martin Wojciechowski's research.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons.

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Local Fly Food Secrets

- Author(s): Madeline Sopa

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: 27 Jun, 2022

- Date accessed: 17 May, 2025

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/local-fly-food

APA Style

Madeline Sopa. (Mon, 06/27/2022 - 16:02). Local Fly Food Secrets. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/local-fly-food

Chicago Manual of Style

Madeline Sopa. "Local Fly Food Secrets". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 27 Jun 2022. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/local-fly-food

MLA 2017 Style

Madeline Sopa. "Local Fly Food Secrets". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 27 Jun 2022. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/local-fly-food

Cacti are important host plants for a variety of animal species. One such species, the Sonoran Desert fly, may even be experiencing local adaptation as a part of their use of prickly pear.

Painting by Amenakay.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.