Bacteria in the Belly of the Bee

What's in the Story?

All day and all night, a massive party is going on in our bodies. The party goers are the billions of bacteria that live inside each of us. Every single one is eating and multiplying as much as they can. It is important we keep hosting this party, because in return, the bacteria give us essential vitamins, help us digest food, and even fight off invaders. It turns out a similar party is happening in the bodies of most animals, including honeybees.

In the PLOS Biology article, “Antibiotic Exposure Perturbs the Gut Microbiota and Elevates Mortality in Honeybees,” scientists show us just how much honeybees need their bacterial party. They found that medicine commonly given to bees changes their bacterial community, which increases the risk of honeybee death.

What’s a Microbiome?

As you eat, play, and work, you pick up different types of bacteria. A lot of this bacteria ends up in your gut (also called your digestive tract). Some of these bacteria are bad, and can cause illness. But many of these bacteria help you stay healthy. Good bacteria help you break down food, fight off bad bacteria, and even influence your behavior. Together, the bacteria in your gut are called your gut microbiome.

The gut microbiomes of people have changed a lot over time. The bacteria we have in our bodies today are very different from the bacteria your great-great-great-great-great-great grandparents had in their bodies. Scientists believe many of the major health concerns of today are caused by a lack of our ancestor’s full gut microbiome.

One reason we may have lost some of this good bacteria is because we use antibiotics to treat bad bacterial infections. Even though we need them to treat our aches and pains, antibiotics may be killing some of our good bacteria. To understand the effects of antibiotics on human health, we can observe the effects of antibiotics in other animal species.

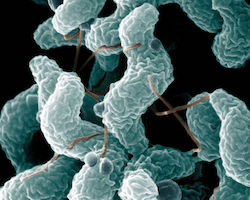

One useful animal to look into is the honeybee. Beekeepers have been treating honeybees with antibiotics almost as long as we have been treating ourselves with antibiotics. Honey bees also have another thing in common with humans: Unlike other insects, honeybees acquire their gut microbiomes from the other bees in their colony. In the same way, we humans get some of our bacteria from the other people we interact with.

Honeybee Gut Bacteria

To understand how an antibiotic affects the gut microbiome, scientists first collected two groups of honeybees. They fed these groups sugar water, but one of the groups’ water was laced with antibiotic called tetracycline. After five days, the scientists collected bees from each group to find out what happened to their gut bacteria. To do this, they dissected or cut out the bee gut and mixed it in a liquid that extracts the DNA (including the bacteria’s DNA). Then, they ran something called a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on the mixture.

PCR is used to make lots of copies of DNA. Once the DNA copies were made, the scientists ran them through a machine that figures out what DNA code is present, and how much DNA is there. By matching the DNA code to the bacteria it is from, the scientists can figure out which bacteria the bees had. By figuring out how much DNA is there, they can calculate how much of each bacteria was there. The scientists found that the antibiotic caused the bees to have less gut bacteria, and some bacteria were more affected than others.

Do Antibiotics Hurt Honeybees?

What else happens to honeybees when they are exposed to an antibiotic? The scientists put some bees from each group into a beehive. Three days later, the scientists went back to see if they could find them. They could not find as many bees who had fed on the antibiotic as they could find bees who fed on sugar water only. This suggests that the antibiotic contributed to an early death in the bees given antibiotics compared to the bees that only had sugar water.

Maybe the antibiotic itself is what killed these bees, instead of changes in gut bacteria. To test this, the scientists raised some honeybees with a natural gut microbiome and some without a gut microbiome. When they gave both of these groups the antibiotic, they observed a high death rate in honeybees who had a natural microbiome, and no change in death rate in the honeybees with no microbiome. This shows that while the antibiotic itself doesn’t hurt honeybees, its effect of reducing the gut bacteria does hurt them.

What Does the Antibiotic Do to Good Bacteria?

So now that we know what happens to the honeybees, let’s think smaller. What happened to the gut microbiomes of the bees who fed on the antibiotic? Well, the scientists found that these honeybees had a gut microbiome that was always changing. The bees only fed sugar water had a stable (or unchanging) microbiome.

As we now know in humans, a stable microbiome is a healthy microbiome. The bees who fed on the antibiotic were likely not as healthy as the other group. And why is a healthy microbiome important? Well, a healthy microbiome is a defense system that fights off invading bacteria. So, the scientists wanted to see if bees who had an unhealthy microbiome were still able to fight off bad bacteria.

They gave two groups of bees a bacterium called Serratia and waited to see how many bees died over a few days. The first group of bees were treated with antibiotics, and the second group was not. The researchers found that the bees who were treated with antibiotics died more often after being exposed to Serratia than the group who did not receive antibiotics. This was likely because the microbiomes in the antibiotic-fed bees were not strong enough to kill the Serratia bacteria.

Are Antibiotics Anti-honeybee?

These scientists were able to make some useful conclusions about antibiotics and the honeybee gut microbiome. They found that the gut microbiome of a honeybee plays an important role in honeybee health. When the gut microbiome is damaged by antibiotics, it can have a negative impact on a honeybee’s survival. We depend on bees to support our production of food, but it turns out that giving bees antibiotics could be doing more harm than good.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Bee on white flower by Zeynel Cebeci.

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Bacteria in the Belly of the Bee

- Author(s): Tyler Quigley

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/bee-microbiome

APA Style

Tyler Quigley. (). Bacteria in the Belly of the Bee. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/bee-microbiome

Chicago Manual of Style

Tyler Quigley. "Bacteria in the Belly of the Bee". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/bee-microbiome

Tyler Quigley. "Bacteria in the Belly of the Bee". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/bee-microbiome

MLA 2017 Style

Could the antibiotics beekeepers use to protect honeybees also be hurting them?

Learn more about the lives of honeybees in our story Bee Bonanza.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.