Hunting for Deadly Bacteria

What's in the Story?

The pitter pattering of gentle rain finally starts to fade. Soon you can see the storm move past the island and into the sea. Then, the Caribbean sun shines across the farm once again. You quickly head outside to ride your new bike. You decide it would be really fun to race through the deep puddles by the cattle pen, but you end up crashing into a rock that was hidden in the water. You scrape your knees and smell a little like cow manure, but otherwise feel good enough to keep playing.

A few days later, you wake up with a fever and a headache and you think you might throw up. You go to see a doctor. The doctor runs several tests and figures out that you have an illness called leptospirosis. One doctor explains that you probably caught it when playing near the cattle pen. Leptospirosis is a disease often found in tropical places.

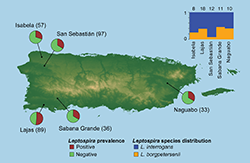

Knowing how leptospirosis is spread can make it easier to prevent disease. In the PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases article, “The prevalence of Leptospira among invasive small mammals on Puerto Rican cattle farms,” scientists investigate what animals carry the bacteria in rural areas of Puerto Rico.

What is Leptospirosis?

Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico in 2017. It left many people without electricity. Flood waters entered houses and streets were under water. People had to wade through the water to try to find help. As the days passed, several people become very sick. Doctors discovered that these people caught a disease from the flood water. This disease was called leptospirosis. It was a type of zoonosis.

Zoonoses are diseases in animals that can make humans sick. You may be familiar with many zoonoses. When people get rabies from an animal bite, that’s a zoonosis. Another is Salmonella, which you can get from eating raw chicken. Leptospirosis is a zoonosis. It is caused by bacteria called Leptospira. There are about 10 different types of Leptospira that can make people sick. All people can catch this deadly disease if they are exposed.

Leptospirosis is most common in tropical places. These areas are warm and get a lot of rain. People usually catch the disease from small mammals that carry Leptospira. Some animals that carry it are rats, mice, and mongooses. Leptospira live in animals’ kidneys. When an animal urinates, Leptospira is in the urine. This urine can then end up in puddles, rivers, and ponds.

When people are exposed to that dirty water through cuts and scrapes, the bacteria can enter their bodies. That’s how animals spread the pathogen to people. Once infected, people can start to feel like they have a bad flu. They can even die if they don’t get help quickly. But how might we stop this disease before it can infect someone? One of the best ways to prevent sickness is to know what animals are spreading the bacteria so that people can avoid them.

The Hunt for Deadly Bacteria

Farm workers and cows in Puerto Rico were getting sick with leptospirosis. But nobody knew how they were catching the disease. Scientists decided to figure out how the farmers and cows were coming into contact with the bacteria.

Here, scientists are putting a radio collar on a mongoose's neck. These collars use radio waves to let scientists track animals. This allows scientists to figure out where an animal is located. Photo courtesy of Jose Martinez.

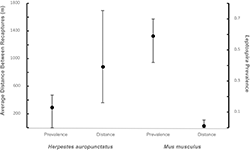

Scientists started studying wild animals at the farms. They traveled all around Puerto Rico and trapped rats, mice, and mongooses. These species are the only wild mammals near the farms that were likely to spread the pathogen. Early each morning, the researchers would trap animals on the farms. They set traps all over the farms for several weeks. They wanted to know where people and cows were more likely to catch leptospirosis on the farm. The scientists also put radio collars on mongooses. Because they were the largest of the test animals, they were likely to move the farthest. These collars are like miniature radio stations. They let scientists “tune in” to figure out where a collared mongoose is located. The scientists could then figure out how far mongooses travel.

The best way to test for Leptospira in animals is by looking at their kidneys. Scientists collected the kidneys of 124 mice, 99 rats, and 89 mongooses. In the lab, they then extracted DNA from the kidneys. A special machine was then used to determine if the kidney DNA contained Leptospira DNA.

Farmers at Risk of Disease

The scientists found out that the rats, mice, and mongooses at all the farms carried Leptospira. Mice were the most likely to carry it. Mongooses were the least likely to carry it. The scientists also found two types of Leptospira that can cause disease in humans and cattle. Because animals on the farm carried the bacteria, humans and cows were at risk for exposure.

At two farms, animals near buildings and ponds were more likely to carry the bacteria. At another farm, they trapped several infected mice around a junk pile.

The scientists also found out that mongooses travel far away from the farms. Mice tend to stay very close to the farms. So, it is possible for mongooses to carry Leptospira away to nearby farms.

The Road to Recovery

Based on what they found, the scientists made some suggestions to the farmers. One suggestion was to remove junk piles from their farms. This small step can make a big difference. This is because rats and mice will often live in these piles.

If fewer rodents are on the farm, then there will be less Leptospira being spread. If there are fewer rodents, it will also be less likely that mongooses are exposed, as they share water and mongooses eat rodents. Fewer infected animals lead to less bacteria being spread on the farm. That means people will also be less likely to catch leptospirosis.

Close-up of pig on farm by Jai79 via Pixabay. Leptospira image (article thumbnail) by the CDC.

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Hunting for Deadly Bacteria

- Author(s): Kathryn Michelle Benavidez Westrich

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/hunting-deadly-bacteria

APA Style

Kathryn Michelle Benavidez Westrich. (). Hunting for Deadly Bacteria. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/hunting-deadly-bacteria

Chicago Manual of Style

Kathryn Michelle Benavidez Westrich. "Hunting for Deadly Bacteria". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/hunting-deadly-bacteria

Kathryn Michelle Benavidez Westrich. "Hunting for Deadly Bacteria". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/hunting-deadly-bacteria

MLA 2017 Style

We think about the livestock that lives on farms, but many of us forget about all the other rodents and other animals that are a part of farm life. In some areas of the world, rodents more commonly carry deadly diseases that can be dangerous for humans.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.