Sleeping Viruses

What's in the Story?

Sleepy time is a great time. You might bring all your blankets, stuffed animals, and pillows together for comfort as you lay down, close your eyes, and let your mind wander into dreamland. As you daydream about sleep, ask yourself this: How do you know when someone (or something) is sleeping? That may sound like a silly question, but in some cases, it’s very important. It is a question that scientists are trying to answer about Herpes Simplex Virus.

What’s a Virus?

Viruses are microorganisms that are built to infect cells. They can’t reproduce on their own, but can take over cells in plants, animals, fungi, or bacteria. They then use the cell’s own parts to make more viruses.

Herpes Simplex Virus is a unique virus. When it infects a cell, it sort of decides whether to replicate or to go to “sleep.” When I sleep, I may toss and turn, but what does Herpes Simplex Virus do while it sleeps? This is what scientists attempted to answer in the PLOS Pathogens article, “Lytic Promoters Express Protein During Herpes Simplex Virus Latency.”

What is Herpes?

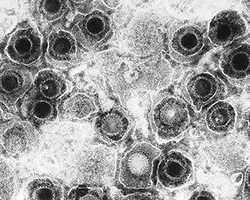

Herpes Simplex virus (HSV) is a virus that is passed by touch. If you have ever seen someone with a cold sore, then you have seen HSV in action. This virus is tricky, it hides from our immune systems, inside our nervous systems. By hiding in the nervous system, HSV can stay hidden in neurons (the cells of our nervous systems) for our entire lives!

Nerves of Steel

Neurons are very important. They are like the electrical wires of our bodies. They tell our muscles to flex and are the main cell type in our brains. If you have ever stubbed your toe or gotten a paper cut, you understand another important part of the nervous system: transmitting sensory information. Certain sensory cells can experience your surroundings and send information about it to your brain. These sensory neurons are where HSV hides from the immune system.

Lytic, Latent, and Sensory Neurons

As HSV enters and infects a skin cell, the virus makes its way to the nucleus (the headquarters of the cell) and begins to replicate. The virus makes thousands of copies of itself, which makes the cell get sick and die. HSV doesn’t mind because its copies have already gone off to infect other cells. This form of infection is called a lytic infection.

When HSV replicates in skin cells, it eventually heads toward a sensory nerve. When it reaches the neuron’s nucleus, it does not go through the same lytic infection cycle. Instead of replicating, it does something unusual - the virus goes dormant. This is called a latent infection. We do not fully understand why HSV goes latent in neurons, but we need to understand latency if we want to create a vaccine for this virus.

When HSV goes latent, it hides from the immune system. In these cases, traditional vaccines have not been good at stopping HSV infection. But, rather than figuring out a way to get the vaccines to work, scientists have a different idea. They are interested in developing a method to keep HSV latent, so the virus never reactivates. This is why it is important to understand HSV latency.

A Latent Virus

Lytic and latent infections differ in many ways, mainly in protein production. During lytic infections, HSV makes proteins so it can replicate. Some of these proteins are used to build a cover for its DNA. HSV must actively produce protein or else it will not be able to replicate. Before this study, scientists thought that during latent infection, HSV did not produce proteins. But it turns out that they do.

I Could Do That in My Sleep

When a tiny virus puts itself to “sleep,” most researchers stop paying attention. They don’t see any proteins being produced, so they assume that the virus is somewhere off in dreamland. However, it turns out that HSV may produce some proteins while latent. They are proteins that are usually made during a lytic infection. If the virus is supposed to be asleep, how are these proteins being made?

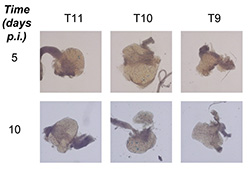

To figure this out, the scientists made mutant HSV viruses. These mutant viruses made CRE recombinase, a special protein that activates a silenced gene in the infected cells. This gene allowed the neurons to glow blue (in the presence of a special added chemical) if the protein was being made. This would allow the scientists to see when the proteins were made. The proteins they were tracking were proteins usually produced during lytic infection.

Scientists infected mice with these mutant viruses and tracked when lytic proteins were made in the mice’s neurons. They saw the mice neurons glowing blue, during both lytic and latent infection. This meant that lytic proteins were being produced even while the virus was “asleep.”

Hiding is Better than Fighting

Creating a vaccine for HSV is difficult because it hides within the nervous system. HSV travels to the nervous system so quickly that it is challenging to have an effective immune response that will prevent it from entering our nerves. One solution to this problem may be to keep HSV latent so that it never wakes up from its deep slumber. This could prevent the virus from causing disease. For this solution to work, we must understand why HSV goes into latency in the first place. Studies like this one are just a start, we still have a lot to learn about what viruses do while they are sleeping.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Chickenpox image by Jonnymccullagh. 3D herpes virus by Thomas Splettstoesser.

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Sleeping Viruses

- Author(s): Ian Vicino

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/sleeping-viruses

APA Style

Ian Vicino. (). Sleeping Viruses. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/sleeping-viruses

Chicago Manual of Style

Ian Vicino. "Sleeping Viruses". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/sleeping-viruses

Ian Vicino. "Sleeping Viruses". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/sleeping-viruses

MLA 2017 Style

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.