Think Fast!

What’s in the Story?

You're sitting in a quiet classroom. You see the students around you going through the quiz like it's no big deal, quickly scribbling their answers down. Looking back down at your quiz, you feel nervous. You tap your pencil against your desk and try to remember those last few answers. You start thinking about how much you want to get a good grade. Suddenly, the correct answers come to you. You write them down, and that nervous feeling in your stomach goes away.

Do you ever wonder where that nervous feeling comes from and why it seems to help you think a little better? Perhaps the thought of a good grade motivates you to remember those last few answers. In the PLOS Biology article “Motivational Salience Signal in the Basal Forebrain Is Coupled with Faster and More Precise Decision Speed,” scientists investigated why we tend to make better decisions when we are motivated.

A Nervous System

A specific part of the frontal lobe, the basal forebrain, is very important for learning and memory. What does this have to do with your motivation for doing well on a test? Well, scientists thought that the basal forebrain could be an area that lets people respond to motivational cues, including the desire for a good grade. This is what they decided to test.

Measuring Motivation

Motivation is the desire to do something and it's usually due to some sort of reward. It is a reason a person has for acting in a particular way or carrying out some action. However, we are all motivated by different things.

Salience refers to how much something stands out, like a red piece of candy in the middle of a bunch of blue ones. Motivational salience, then, is something that stands out to you and makes you feel motivated. How much something stands out to people might differ because they might be motivated by different things.

For example, imagine you are taking a quiz in class. Your teacher offers you 10 points of extra credit for one hard assignment or 1 point of extra credit for an easier assignment. You can only do one. Some people would pick the easier assignment so they would have more time for other things. Other people might pick the harder assignment because the points are more important to them. You would probably pick the one with more extra credit if you were motivated to improve your grade. So the 10 point assignment would stand out to you. This is an example of motivational salience.

Scientists used rats to test these differences in motivation. Why rats? Usually, animals are used for experiments when using a human would not be possible. Scientists wanted to record from the basal forebrain, which meant that they needed to put electrodes into the brain. Unless a person is having surgery, it is unlikely that she or he would allow a scientist to do this. Because of this, scientists will often use an animal model so that they can learn more about the way human bodies work.

If rats were motivated with something positive, like a reward, scientists guessed they would learn faster than when there was no reward. They also thought larger rewards would make for faster learning. To study this, they had rats learn the relationship between different cues and rewards.

Brain and Behavior

The scientists played sound to the rats that acted as a cues. The rats were then given a reward in response to each cue. These cues were motivational for the rats because from the cue, the rats could tell how big of reward they would receive. A “large” sound would mean a big reward; a “small” sound would mean a small reward. In all, they wanted to test if the rats would match these cues with the size of the reward.

The reward in this case was cool water. Cool water was especially rewarding because the rats were not given water on the day before the experiment. Because the rats were thirsty, cool water was a very motivating reward. To measure the rats’ behavior, the scientists measured something called reaction time. Reaction time was how quickly the rats drank the water after they heard the sound.

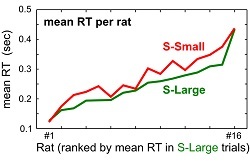

Scientists found that the rats performed the tasks more quickly when they used the sound cue that meant a larger reward versus a smaller one. They concluded that the rats were more motivated by the sound that gave them a larger reward.

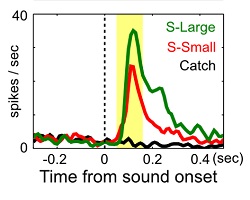

To test the rats’ brain activity during the experiment, scientists measured the electrical activity in each rat’s basal forebrain. They did this by putting very small electrodes into the brain to measure the brain cells in this region. If the basal forebrain was a part of the brain involved with motivation, they expected to see more electrical activity when there was a larger reward. The rats had the most activity in the basal forebrain when they heard the sound for a large reward.

Bringing It All Together

The results showed that the rats performed the task more quickly when the reward was higher. This meant that their behavior changed when they were more motivated. The results also showed that the basal forebrain was more active when rewards were higher. This meant that the brain was responding differently to the two sizes of the reward.

Scientists concluded that the increased activation in the basal forebrain might be what was making the rats move more quickly when a larger reward was available. This part of the brain could be one of the areas that allow us to respond to motivation.

So How Does This Relate to People?

Besides explaining that your brain is more active and responds more quickly when larger rewards are offered, there are some other important things we can learn from these findings. This experiment supports the connection between the basal forebrain and motivation. Because motivation helps us to perform one action versus another, scientists think that the basal forebrain may be an area that is active when we make decisions.

People with conditions such as schizophrenia or depression can sometimes have trouble making decisions. Scientists believe that a problem with the basal forebrain may be causing some of the symptoms in these conditions. These findings could lead us to a better understanding of these problems and how to treat them.

But these findings might apply to you anytime you have to think fast. So the next time you’re taking a test and you are motivated to get that higher grade, thank your basal forebrain.

Additional Images via Wikimedia Commons. Photo of child raising their hand by Airman 1st Class Gustavo Castillo.

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Think Fast!

- Author(s): Garrison Leach

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/think-fast

APA Style

Garrison Leach. (). Think Fast!. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/think-fast

Chicago Manual of Style

Garrison Leach. "Think Fast!". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/think-fast

Garrison Leach. "Think Fast!". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/think-fast

MLA 2017 Style

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.