Tick Bacterial Trick

What's in the Story?

You are in the hot, sticky, New York summer, waiting underground to get on the next subway. It pulls up, but all the subway cars you can see are packed full. You don’t want to have to wrestle your way on to compete for space, so you decide to wait for the next one.

Most of the time, the way we act or respond to something depends on the conditions of the environment. When conditions (such as how full a subway car is) change, so do our responses. This is true for most living things. An organism’s response, whether how it behaves or how its body functions, can change with conditions.

But what about organisms we might not usually think of as very "responsive"? What about bacteria? If bacteria are about to enter a new host’s body, does the presence of other bacteria affect whether or not it goes? It turns out that it does.

When a tick infected with the bacteria that causes Lyme disease bites a mouse (its “host”), the disease-causing ability of the bacteria may change, depending on the health status of the mouse. Researchers looked at how host health affects disease transmission from ticks in the PLOS Pathogens study, “Infection History of the Blood-Meal Host Dictates Pathogenic Potential of the Lyme Disease Spirochete Within the Feeding Tick Vector.”

Ticks and Lyme Disease

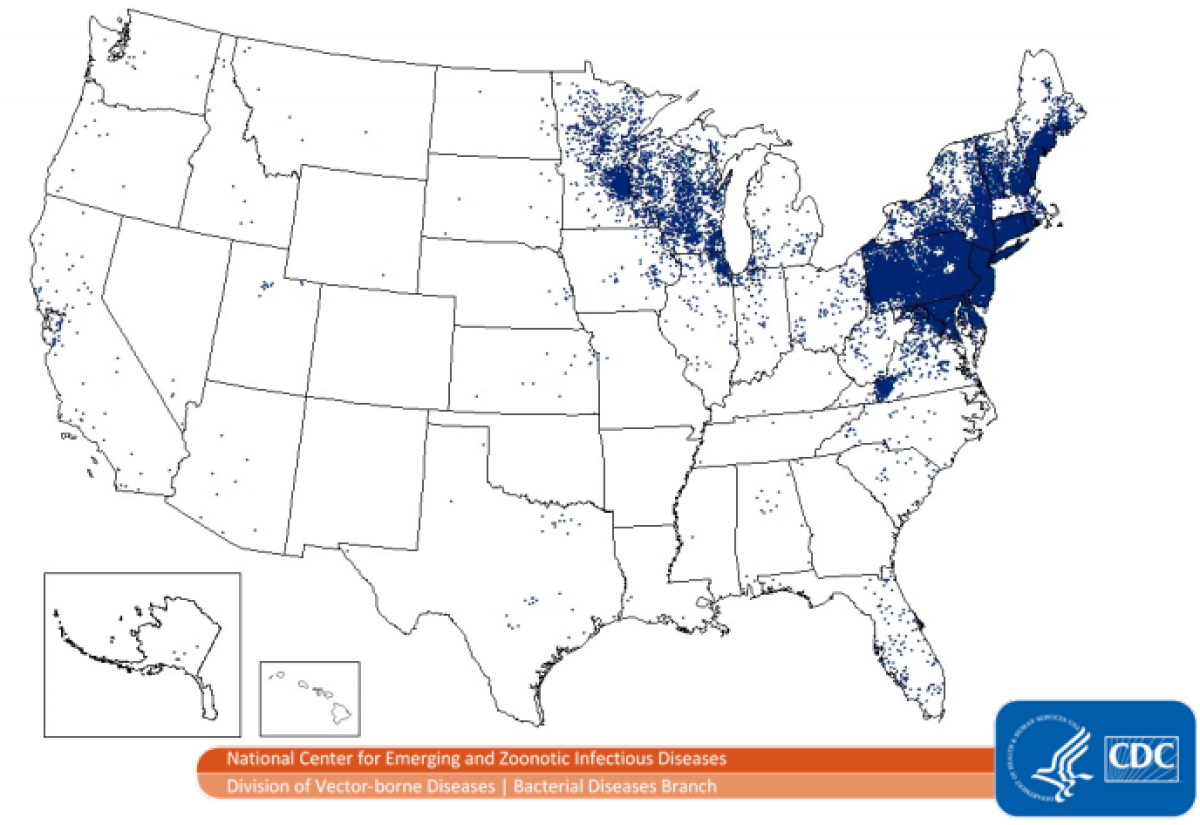

You see it when you’re getting ready for school—a red bullseye around your bellybutton. Last week, a few days after you went hiking in upstate New York, you found a tick attached there. Your bullseye rash is a sign that the tick may have given something other than just a bite—you may have Lyme disease. Lyme disease is caused by bacteria known as Borrelia. The disease affects the skin, joints, and the nervous system, and affects around 300,000 people per year just in the United States.

Within the ticks, the bacteria live in the digestive system (also called the gut). Ticks dig into the skin of another animal and anchor themselves there to start feeding. The feeding process might take a few days. As blood reaches the gut of the tick, the Borrelia bacteria there may become active. These bacteria then move into the tick’s bloodstream, then into the tissue where it makes saliva. From there, it can enter the saliva and, eventually, the host’s body. This is how Lyme disease is passed.

Lyme disease is mainly caused by four species of bacteria in the Borrelia genus. In some areas where these bacteria are common, one population of ticks or of hosts likely has several different strains (slightly different types) of the same bacteria.

These bacteria succeed by being passed between their two main groups of hosts: ticks and small vertebrate hosts (like rats and other rodents). Ticks are the disease vector, meaning they are the way that the disease gets passed along to other hosts. Ticks are not affected by the Lyme disease they sometimes carry. Before the bacteria go anywhere, they get a hint of what they are in for. When the tick starts feeding and blood enters its gut, the bacteria there are exposed to the host’s blood. From the blood, they get information about the health of the host.

Researchers wanted to find out how host health, which may include existing Borrelia infections, affects the bacteria. Specifically, they were curious how this changes the bacteria’s pathogenicity, or its potential to cause disease.

The Tick Test

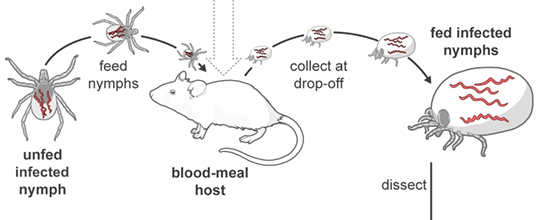

To test this, mice were placed into one of several groups to receive tick treatments. A “tick treatment” means that infected ticks were placed on the mice to feed. Mice were either: 1) “naïve” (meaning they had never been infected with any Borrelia bacteria), 2) infected with the same Borrelia bacteria strain that the ticks were carrying, or 3) infected with another type of Borrelia bacteria strain, different from the one the ticks had.

These treatments were used on mice with two kinds of immune systems. Mice were either “wild type,” meaning they had normal, fully functioning immune systems, or they were “immune-deficient,” meaning their immune systems were not working properly.

These mice were then all exposed to ticks that had one strain of Borrelia bacteria. After the ticks were allowed to feed on the hosts’ blood for a full meal, the ticks and the mice were all tested to see whether the mice were infected, and to see how pathogenic the bacteria in the ticks were.

The Bacterial Trick

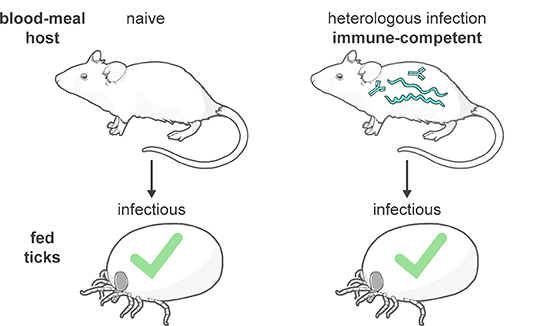

The researchers found that the potential for these bacteria to successfully infect a mouse through a tick bite depends on two factors of mouse health. It depends on whether or not the mouse is already infected (and with which strain of bacteria), and on whether the mouse’s immune system is working correctly.

When ticks fed on naïve mouse blood, the bacteria in the ticks became highly infectious. The bacteria in the ticks also became highly infectious when the mouse was infected with a different strain of the Borrelia bacteria. In both of these tests, conditions in the host’s blood were favorable, so the bacteria activated and multiplied, and then invaded the host.

However, when the mouse was already infected with the same strain of bacteria that was in the tick, the bacteria in the tick were not infectious; they did not activate and multiply. But what happened in the mice that were immune deficient? In immune-deficient mice, even when the strain of bacteria was the same, the bacteria in the tick became highly infectious.

This final result helps us understand what is going on. Because the infection is different in wild-type versus immune-deficient mice, this let the researchers know that the inactivation of the bacteria was in response to the mouse's immune system. Usually, immunity occurs within a host’s body. After a host has been exposed to a specific strain of bacteria, they produce antibodies against that strain, helping them kill off more invaders as they enter the body. However, in this case, researchers found that the host’s antibodies made the bacteria inactive while it was still in the tick.

This image shows the main results from the experiment. Click for the full story.

These findings suggest that the bacteria in a tick can be affected by their new potential host before they ever leave the tick (and before they are activated).

If the mouse is already infected with that strain of bacteria, the mouse's antibodies make that same strain inactive. This helps protect the host from a worse infection.

All organisms respond to the environment around them, whether it's a crowded subway or the blood of a potential host. Understanding the responses of bacteria and other microbes that affect health can help us learn more about how some diseases spread.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Lyme disease map image by the CDC.

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Tick Bacterial Trick

- Author(s): Karla Moeller

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/tick-lyme-disease

APA Style

Karla Moeller. (). Tick Bacterial Trick. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/tick-lyme-disease

Chicago Manual of Style

Karla Moeller. "Tick Bacterial Trick". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/tick-lyme-disease

Karla Moeller. "Tick Bacterial Trick". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/tick-lyme-disease

MLA 2017 Style

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.