Getting to Know the Germ Layers

Illustrated by: Sabine Deviche

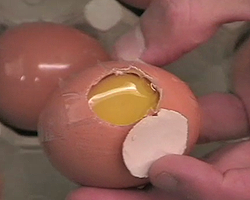

You crack an egg into a bowl and look closely at the golden yolk and the clear gel around it. You notice a tiny white spot within the yolk – that means that a sperm has fertilized this egg, and it could grow into a baby chicken. But what happens to a fertilized egg that makes it turn into an entire animal?

The egg you are inspecting is actually one big cell. For a fertilized egg to become a whole organism, that cell must divide to create more cells. Those cells then have to differentiate so they know what function they need to perform in the body.

Cells differentiate based on where they will end up in the body. For example, a cell that is going to be part of a lung has to perform a different function than a cell that will be part of the stomach.

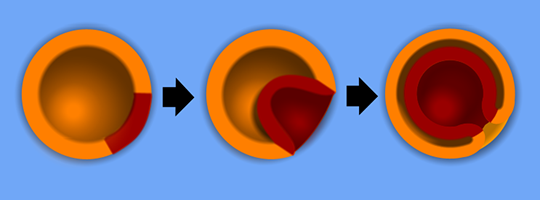

But before cells can differentiate, the embryo must go through a process called gastrulation. During gastrulation, an embryo’s cells split into separate layers called germ layers. All animal embryos, except sponges, develop two or three germ layers. The germ layers will give rise to every tissue and organ in the body.

In the Embryo Project article “Germ Layers,” writers explore the three germ layers that arise during development.

What's in the Story?

Imagine you are looking inside a fertilized egg as it develops. The egg yolk, made of a hollow ball of cells, begins dividing–that means gastrulation is starting. You see the cells split up into two spheres, one within the other, like a balloon inside a bigger balloon. The inner sphere, or germ layer, is called the endoderm, and the outer germ layer is called the ectoderm.

Embryos of complex organisms, like humans, form three germ layers. In human embryos, the endoderm and ectoderm interact to form a third germ layer between them. That layer is called the mesoderm. Let’s take a closer look at each layer and the body parts they will form.

The Ectoderm

The ectoderm is the outermost layer of the embryo and has two parts. The first part is called the surface ectoderm. Cells in the surface ectoderm will develop into outer (surface) body parts… makes sense, right? These will become body parts like skin, nails, and hair.

The second part of the ectoderm is the neuroectoderm. The neuroectoderm will form the central nervous system of the embryo. The central nervous system, or CNS, has all of the nerves that control all of an animal’s activities. In vertebrates, or animals with spines, the CNS includes the brain and spinal cord.

The Mesoderm

Many animals, like humans, have a middle germ layer called the mesoderm. Cells in the mesoderm gather in specific places across the embryo. A cell’s location in the mesoderm layer determines what kind of cell it will become.

The mesoderm forms the embryo’s heart, most muscles, bone, and connective tissue, which gives structure to organs in the body. Animals that have a mesoderm get internal organs. For example, stomachs and intestines. But many organisms do not have a mesoderm and don’t form the internal organs that we do. Organisms without a mesoderm, like jellyfish, are less complex and don’t need organs like brains or hearts to function.

The Endoderm

The endoderm is the innermost germ layer. This layer of cells forms a type of tissue called the epithelium. It lines many internal organs, like the digestive tract, liver, pancreas, and lungs. The epithelium will cover and protect those organs like a thin suit of armor.

Goodbye, Gastrulation!

After the germ layers separate in gastrulation, cells begin to take on their unique jobs in the organism. As this happens, cells in each germ layer start to group together to form tissues. Then, similar tissues group together to make whole organs, like muscles, bones, hair, or even your heart. Organs can have several tissue types with different cells. For example, the heart has both muscle and connective tissue.

Our cells do a lot of different jobs to keep us alive. Without differentiation, our cells would not know what their jobs were. If all of our cells were doing the same thing, we wouldn’t have separate body parts at all! It’s pretty amazing how all of those body parts can come from one little egg.

Discovering Germ Layers

He slices through the egg shell, creating a small hole through which he can see the egg yolk. Taking another egg shell, he carefully trims the egg down until he has created a perfectly sized patch for the hole he just made. When he wants to look inside, he opens the patch. Otherwise, he leaves it closed, so the egg doesn’t lose too much water.

With this method, young scientist Christian Heinrich Pander was able to look inside of a chicken egg as it developed over two weeks. Pander looked at the developing egg in 1817 while he was a doctoral student at the University of Würzburg in Germany. What he saw in the egg changed our understanding of development: he discovered the germ layers.

Pander’s discovery sparked hundreds of years of research. By the 1860s, scientists began comparing germ layers in various animal embryos. In doing so, scientists came up with germ layer theory, the idea that germ layers always developed into the same set of organs in every species.

Does this theory sound right to you? Not all scientists agreed with the idea.

In the late 1870s, brothers Oscar and Richard Hertwig argued that germ layers could grow into more structures than other scientists thought. They spent three years publishing evidence of this, showing that germ layer theory wasn’t right after all.

Shifting Cells

In 1901, Charles Sedgwick Minot, a professor at Harvard, also thought of a theory that changed how we see cells.

Minot predicted that moving cells from one germ layer to another would make the cells change to become like the other cells in their new germ layer. But, Minot never tested his theory.

Luckily, in 1924, Hilde Proescholdt Mangold from Freiburg, Germany, did an experiment that supported Minot’s theory. Mangold moved cells from the ectoderm layer of a newt embryo to a different germ layer on a second newt embryo.

The Jobs of Germ Layers

Can you guess what happened? The cells took on their new role in the second embryo as if it was where they had started. That experiment showed that the jobs of germ layer cells can change, and are not fixed at the start of development.

Scientists still study germ layers today. Many hope that knowing how organisms develop will help us treat diseases. Who knows, maybe the cells that help us start our lives could help save them, too.

This Embryo Tale was edited by Dina Ziganshina and Emily Santora and it is based on the following Embryo Project articles:

MacCord, Kate, "Germ Layers". Embryo Project Encyclopedia (2013-09-17). ISSN: 1940-5030 https://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/6273.

MacCord, Kate, “Endoderm.” Embryo Project Encyclopedia (2013-11-17). ISSN: 1940-5030 https://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/6584.

MacCord, Kate, “Mesoderm.” Embryo Project Encyclopedia (2013-11-26). ISSN: 1940-5030 https://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/6603.

MacCord, Kate, “Ectoderm.” Embryo Project Encyclopedia (2013-12-01.) ISSN: 1940-5030 https://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/6642.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons.

Read more about: Getting to Know the Germ Layers

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Getting to Know the Germ Layers

- Author(s): Claudia Nunez-Eddy , Risa Aria Schnebly

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/embryo-tales/germ-layers

APA Style

Claudia Nunez-Eddy , Risa Aria Schnebly. (). Getting to Know the Germ Layers. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/embryo-tales/germ-layers

Chicago Manual of Style

Claudia Nunez-Eddy , Risa Aria Schnebly. "Getting to Know the Germ Layers". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/embryo-tales/germ-layers

Claudia Nunez-Eddy , Risa Aria Schnebly. "Getting to Know the Germ Layers". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/embryo-tales/germ-layers

MLA 2017 Style

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.