Illustrated by: Marcella Martos

Brimming with Life

With closed eyes, the moist warmth of the air feels heavy in your lungs and your clothes feel sticky with sweat against your skin. Birdcalls, monkey howls, and insect buzzing surround you. Opening your eyes, you find that you are under the shade of a tall forest canopy.

You look up the long trunk of an emergent, a tree that stands nearly 300 feet tall and breaks through the top of the canopy. As you keep looking into the dense vegetation, you start seeing more life—birds, butterflies, and monkeys. You look down where some tree roots have broken through the moist ground. There you see the ants. They crawl over the tree's roots, over the leaf litter, and across the path, letting nothing stop them as they carry bits of leaves back to their nest. You are in a tropical rainforest.

The Rainforest

When you think of the tropical rainforest, you may think of a towering forest dripping wet and full of life. Although most of these rainforests have short dry seasons, aside from lakes, rivers, and oceans, they represent the wettest biome on Earth.

Rainforests have an extraordinarily large number of animals and plants. Over half of all the species of plants and animals on Earth are found in tropical rainforests, but these forests only make up 6% of the Earth's land surface. So, why are these forests so special?

Rain-Forest. Get it?

Whoever first put "rain" in front of "forest" to describe rainforests probably had a pretty easy time making that decision. Rainforests get a lot of rain—between 50 and 260 inches every year. While 50 inches is just over four feet, 260 inches is over 21 feet, which is a lot of water. That level of water is higher than three people standing on each other’s shoulders.

Most tropical rainforests are close to the equator (an imaginary line running around the middle of the Earth, halfway between the north and south poles). Although most are in lowland areas that are close to sea level (the base we use for measuring the height of land, called elevation), some are on tropical mountain slopes. These higher elevation forests are cooler and are called cloud forests.

The Sunny Side

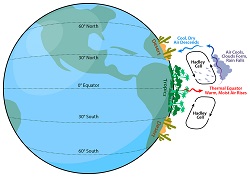

So why does it rain so much in rainforests? Because tropical rainforests are mainly found near the equator in Africa, Central America, and parts of Asia, they receive more intense rays of the sun than you could find anywhere else on Earth. This makes it possible for millions of trees and other plants to grow in this biome. Because the millions of trees release tons of water from their leaves, the air is very humid, or full of water vapor.

The powerful rays of sunlight cause the air to heat quickly. This warm, moist air rises high into the sky and cools. At first the cooling water vapor forms clouds, but as the air rises and cools even more, the clouds turn into liquid water—rain. All of the moisture in the air and the sunlight that warms the air near the equator cause a lot of rain.

- or download the mp3 here.

Images via Wikimedia commons. Additional images by Adrian.Benko and Andre Deak.

Karla Moeller earned her PhD in Biology at Arizona State University, studying how animals survive in different environments. She is an ecological physiologist, a science writer, and a children's book author.

Read more about: Revealing the Rainforest

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Revealing the Rainforest

- Author(s): Karla Moeller

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/rainforest

APA Style

Karla Moeller. (). Revealing the Rainforest. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/rainforest

Chicago Manual of Style

Karla Moeller. "Revealing the Rainforest". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/rainforest

Karla Moeller. "Revealing the Rainforest". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/rainforest

MLA 2017 Style

Of all the biomes, rainforests get the most water and sunlight – two important ingredients for life.

![]() Try our Virtual Biomes

Try our Virtual Biomes

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.