Illustrated by: Jason Drees

Using "Bad" Plants for Good

But what about those plants that are not so friendly? Poison ivy itches, cholla cactus spines hurt, and smoking tobacco can cause cancer, as well as breathing and heart problems.

That leads us to the story of Nicotiana benthamiana, or tobacco, a plant with a bad rap. Smoking cigarettes kills more than 443,000 Americans each year. It also leads to bad breath, rotten teeth, and premature wrinkles.

But these drawbacks didn't worry Charles Arntzen, a plant-loving researcher at Arizona State University's Biodesign Institute. Tobacco was part of his solution to the spread of the often-fatal disease Ebola.

Why Tobacco?

About 15 years ago, Charlie started working with fellow scientists at a San Diego company called Mapp Biopharmaceuticals. In a collaboration between Arizona State University and ZMapp, the medicine used to treat Ebola, was created by using the tobacco plant.

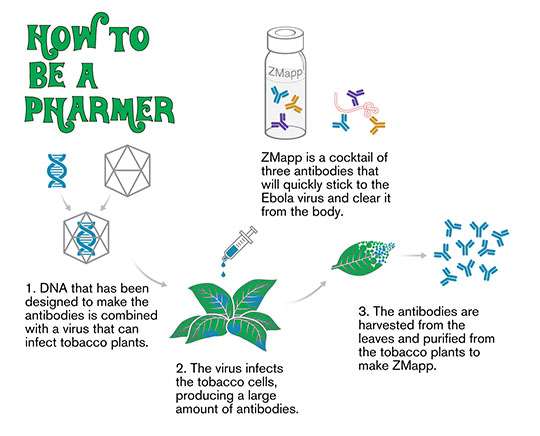

ZMapp is a mixture of three different proteins called antibodies – substances that our bodies produce to fight disease. Unfortunately, in most cases when a person gets sick from Ebola, their immune system cannot work fast enough to stop this very aggressive virus.

So, Charlie and the scientists at Mapp began to look for a way to make antibodies that could be used to “jump start” the immune system of a person who has Ebola. They did this using tobacco.

How Can Tobacco Make a New Drug?

Charlie chose tobacco because it grows rapidly and produces a lot of leaves in just a few weeks. But plants don't usually make antibodies. So scientists have to combine human genes that make antibodies with the genes of a plant virus.

This results in the creation of a synthetic virus which acts like a plant pathogen. However, but instead of causing disease, it causes the tobacco plants to make antibodies which collect in the leaves of the plant. When the leaves are ground up, the antibodies can be purified. So what makes the genes for these antibodies so special? Well, they mimic or act in the same way that the human immune system would when a person is infected with Ebola. Because of this, the purified antibodies can be used to treat Ebola.

The discovery that tobacco plants could be medicine-machines earned Charlie the title of the “godfather of pharming.” In other words, he was farming plants in a way that would turn them into medicines – also known as pharmaceuticals.

Ebola Crisis Calls for a Speedy Response

Charlie's drug was first tested in people in 2014, after an outbreak of Ebola hit western Africa. Not many doctors were available, so physician Kent Brantly and health care worker Nancy Writebol offered to treat Ebola patients. By the end of July, both were diagnosed with Ebola. Despite having good care, they were not getting better. The ZMapp experimental drug was available, but it had never been used in humans. Facing a life-threatening virus, they chose to be the first humans to try the drug. Both fully recovered from Ebola.

Despite success with those physicians, there is still no hard proof that ZMapp was the cure. A few other people used it, and although most recovered, a few did not. More tests in humans were needed.

On February 27, 2015, Mapp Biopharmaceuticals and the U.S. and Liberian governments announced the launch of the ZMapp clinical trial. It was planned that most of the test patients would be in Liberia, a country in which thousands have been infected with Ebola. But thanks to improved public health that has stopped disease spread there has been a decrease new Ebola cases, so there are not enough patients to conduct trials at this time.

Due to the Ebola incident – and certainly continued concern about the spread of dangerous viruses – many more scientists and pharmaceutical companies are interested in preventing future outbreaks.

Continued developments in the use of plants as “medicine machines,” hold potential for other biological threats like Anthrax, Botulism, Plague and Ricin.

“In my mind, ZMapp has been a success both as a medicine and to show that ‘pharming’ works,” said Charlie.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. "Cigarette" by Geierunited at the German language Wikipedia.

Read more about: Tobacco's Wild Ride

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Tobacco's Wild Ride

- Author(s): Dianne E. Price

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/tobaccos-wild-ride

APA Style

Dianne E. Price. (). Tobacco's Wild Ride. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/tobaccos-wild-ride

Chicago Manual of Style

Dianne E. Price. "Tobacco's Wild Ride". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/tobaccos-wild-ride

Dianne E. Price. "Tobacco's Wild Ride". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/tobaccos-wild-ride

MLA 2017 Style

Cigarettes give tobacco a bad reputation, but some species of tobacco plants can be used to make important medicines.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.