Coping with Parasites in a Wild World

What's in the Story?

You return from the bathroom for the tenth time and lie back down on the bed. Hopefully you won't have to get up to barf again. You pull the covers over you, shivering, but you still can't get warm. You probably remember how horrible it feels to get sick. But how do we get better? Your body battles the small, sickness-causing organisms called parasites using two main tools.

One tool your body has is resistance, which means that it kills parasites, helping you resist infection. All your weapons for resistance are carried by your immune system. The second tool is tolerance, which means that you live with the parasites and stay healthy anyway. Tolerance uses lots of your body’s systems. Your body might repair damage caused by parasites or destroy the harmful poisons they make instead of attacking them.

Do wild animals fight parasites the same way you do? Well, we know that they do use resistance. Resistant animals that kill parasites are healthier, they survive better, and they have more kids.

They may also be able to tolerate infection, but this has rarely been studied in wild animals. In the PLOS Biology article, “Natural selection on individual variation in tolerance of gastrointestinal nematode infection,” scientists studied wild animals to see if they use tolerance to fight infections. They also looked at how tolerance affects an animal's success in having offspring.

Take a Walk on the Wild Side

Most of what we know about parasites and disease come from studies on laboratory mice. Laboratory mice are used because they are similar to humans in many ways. We can also easily watch them and do tests to understand how parasites affect them.

But how do we know if what happens in lab mice also happens in wild animals? Well…we don’t. The lab is great for doing experiments, but it’s not like the wild. The lab is clean, animals have plenty of food and water, and there are no predators or bad weather.

But now imagine life as a wild animal. There is always something trying to eat you. The weather rages against you. Everyone else steals your food. It’s totally different from life in the lab. The only way to understand how parasites affect wild animals is to study them in their natural setting.

The Sheep at the End of the World

Scientists have been studying a population of sheep on a tiny, remote, windy Scottish island for the last 30 years. The island is called Hirta and it is in the St Kilda island group, a stomach-churning 3-hour voyage from the west of Scotland. The sheep are called Soay sheep, named after the neighboring island of Soay where this type of sheep was first released.

Some people think these Soay sheep were delivered to the St. Kilda island group by people who were exploring the seas thousands of years ago. The sheep provided a back-up food supply if the people ran out of food on their journey home. This would be kind of like if you left a bag of potato chips hidden in a bush in case you get hungry on your way back from school.

Squirms with Worms

Every year, scientists go to Hirta to catch as many sheep as possible. They build traps made of nets and chase the sheep into them. The scientists then weigh the sheep and take other measurements before letting them go.

Hirta is a harsh place to live where food is often scarce. Scientists have found that being heavier is the best way for sheep to stay healthy, survive, and produce lambs. In fact, having low body weight is bad news for most wild animals.

Just like you, St Kilda sheep sometimes get sick. They don’t usually get the flu or colds though: they get worms. These worms are parasites which live in their guts. Scientists wanted to know which sheep were infected with the most worms. But how could they count worms inside a sheep?

They collected feces (poop) from each sheep. By counting worm eggs in the sheep’s feces, the scientists could estimate how many worms a sheep is infected with. By catching the sheep year after year, they can see how each sheep’s body weight changed with larger and larger worm infections. This is how they measured tolerance.

Worms Are Bad, Tolerance is Good

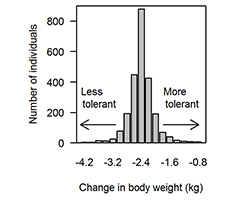

The scientists found that when sheep had more worms, they had lower body weight. This is because worms cause damage to the sheep gut which makes it harder for sheep to digest food. But not all sheep lost the same amount of weight when they had lots of parasites. Some sheep stayed heavy and healthy even with lots of parasites, so were very tolerant. Some sheep lost lots of body weight when they had lots of parasites, so had low tolerance.

The scientists next wanted to know whether a sheep’s tolerance was linked to its fitness. Fitness is a way of saying how well-suited an organism is to its habitat, based on how well it can survive and reproduce. The scientists measured fitness as the number of lambs a sheep produced across its lifetime. Sheep which produce more lambs have higher fitness.

The scientists found that sheep which lost less weight when they had lots of worms had more lambs than sheep which lost lots of weight. In other words, sheep with higher tolerance had higher fitness. This means that there is natural selection for higher tolerance in the St Kilda sheep.

Tolerance Matters, But How Much?

The scientists found that just like with resistance, tolerance can vary from one animal to another. In this case, higher tolerance was linked to higher fitness. In fact, St Kilda sheep use both resistance and tolerance to fight worms and improve their fitness.

The next step is to work out why different sheep have different levels of tolerance. It could be due to the genes they carry or perhaps it’s because some sheep get more food than others.

Working out why resistance and tolerance vary could help us to better understand human disease. It could also help us prevent sickness. This information could also be used to help design better ways of managing diseases in wild animals. In turn, this could help us conserve vulnerable species. Overall, this study goes to show the benefits of getting out of the lab and taking a scientific walk on the wild side.

Additional images via author and Wikimedia Commons. Male tagged sheep image by Adam Hayward.

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Coping with Parasites in a Wild World

- Author(s): Adam Hayward

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: 4 Nov, 2015

- Date accessed: 22 September, 2025

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/parasites-wild-world

APA Style

Adam Hayward. (Wed, 11/04/2015 - 09:38). Coping with Parasites in a Wild World. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/parasites-wild-world

Chicago Manual of Style

Adam Hayward. "Coping with Parasites in a Wild World". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 04 Nov 2015. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/parasites-wild-world

MLA 2017 Style

Adam Hayward. "Coping with Parasites in a Wild World". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 04 Nov 2015. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/parasites-wild-world

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.