Decoding Emotions in the Brain

What's in the Story?

You’re having a fantastic day. The sun is shining, the birds are singing, your favorite song is playing through your headphones and you feel like you could take on the world. You decide you want to share your good cheer, so you give your best friend a call. They pick up, grumble that they don’t want to talk and then quickly hang up before you can get a word in. With that reaction, it’s hard to imagine what might be going through your friend’s head.

We’ve all had that moment where we wish we could read a friend’s, sibling’s, parent’s or significant other’s thoughts. It would make it so much easier to know what’s going on.

Of course, while true mind reading might still only be possible in the pages of your favorite science fiction book, scientists wondered if it was possible to take a step toward making it a reality. In the PLOS Biology article “Decoding Spontaneous Emotional States in the Human Brain,” scientists investigated whether it was possible to record signals from the human brain and predict a person’s current emotional state.

Looking Inside the Brain

So how do we record information from the brain? It turns out that scientists have created many techniques and instruments that allow them to see how activity in the brain is changing. In this study, scientists used functional magnetic resonance imaging, better known as fMRI. Subjects lay down inside a very large tube and the machine measures changes in blood levels in different areas of the brain. Brain cells, called neurons, need oxygen all the time. However, they need either more or less of it when they are more or less active. Scientists use this as a measure of activity in the brain.

Emotional Pattern Recognition

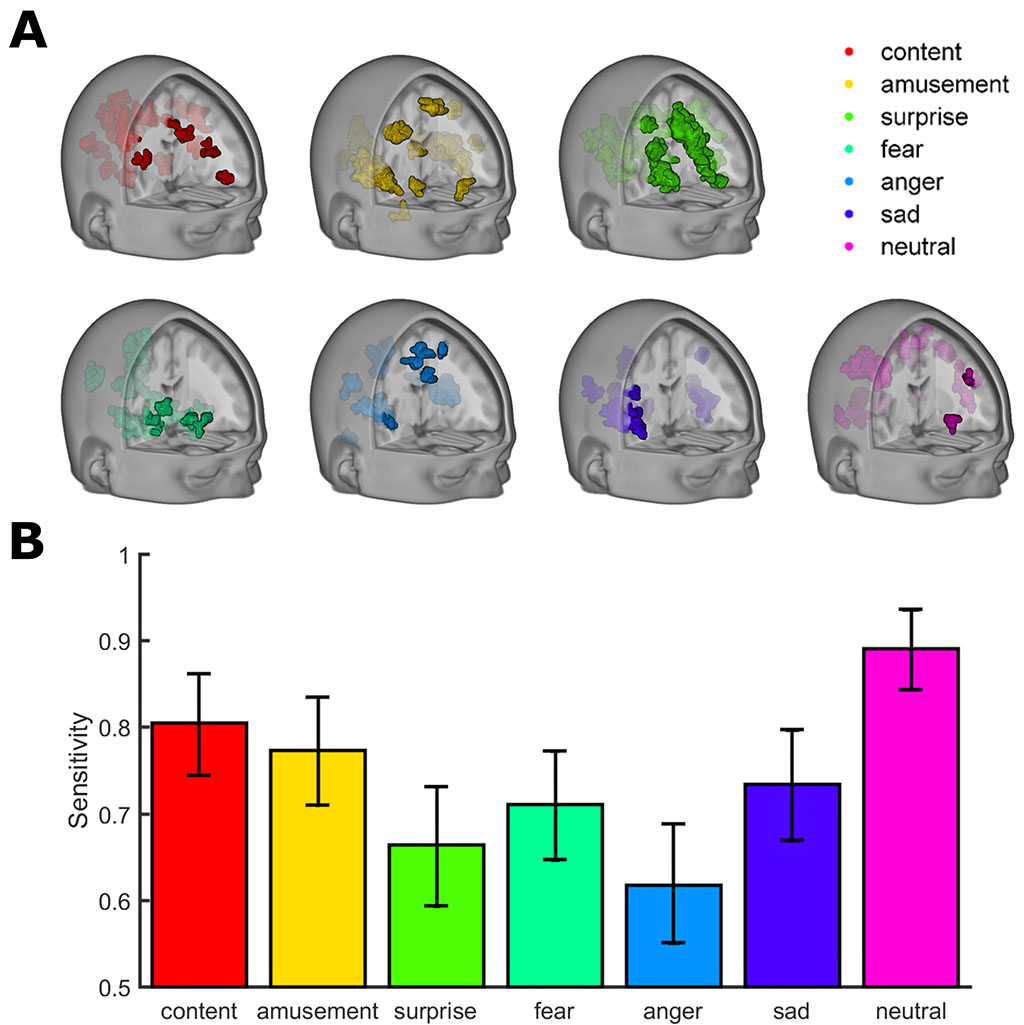

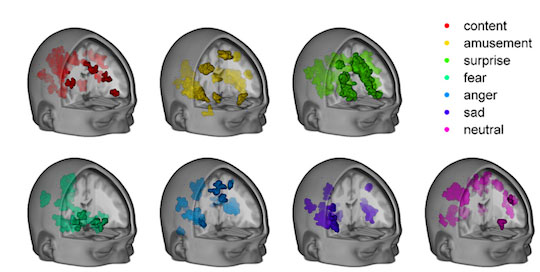

In a previous experiment, scientists found that they could use fMRI to map the brain’s activation for different emotional states, such as fear or happiness. They did this by collecting data when subjects watched a movie or listened to music that was likely to bring about different emotions. This gave scientists an “emotional dictionary”, so to speak, of what brain activity looked like for each of these different states. They could then apply this information to see how brain states relate to emotion.

But, scientists had another question. Could they record the emotional state of a person who was at rest, not watching or listening to anything? In this case, the subject isn’t receiving any stimulus that might make them feel a certain way. Rather, they are just thinking about anything they want, with different emotions naturally occurring due to these thoughts. To answer this, they performed another experiment where they asked subjects to come in, lay in the scanner and let their mind wander. It would be the equivalent of a quiet mental break lying on the couch.

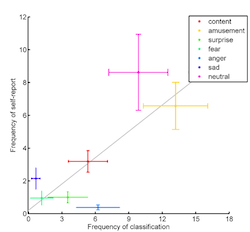

Scientists then compared this data to their emotional dictionary and found that, even during rest, they could relate emotional states to the brain data. Even better, they found that the emotional state that the fMRI data predicted was similar to what subjects reported feeling in a small questionnaire at the end of the scan session. This meant that the brain pattern was correlated with, or good at predicting, how a person reported feeling.

Decode and Recode

The results from these experiments were promising, but scientists were still skeptical. What if it was just a coincidence that the self-report and fMRI data were similar? Perhaps this method could only make very broad predictions about how a person felt. After all, the person was in the scanner for some time, so their emotional state could have shifted quite a bit throughout the experiment. For example, many subjects feel some anxiety when they first get in to an fMRI scanner because the space is a bit tight, and this feeling usually goes away as the scan progresses.

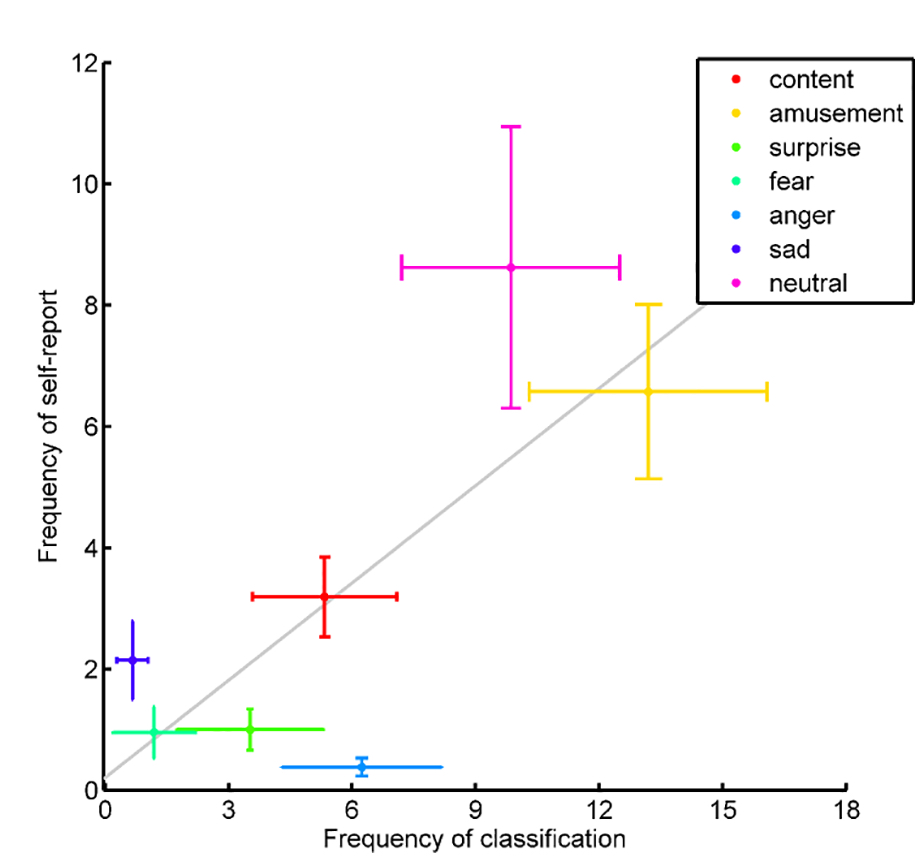

To help address this concern, scientists performed one final experiment. Here subjects were asked to relax in the scanner and let their minds wander. But, periodically throughout the fMRI scan, they were asked to report how they were feeling. So, by the end of the experiment, there were multiple reports of this information. Scientists could then relate these responses to the brain data at many different points in time.

The Neural Code of Emotion

A comparison of these periods showed that the brain activity for different emotions was closely related to subject’s self-reported emotional states. Overall, this meant that scientists were actually able to predict a person’s emotional state. They considered this to be a real-time measurement of emotional states in the brain, one that is much more similar to how our emotional states shift throughout a given day.

While we have a long way to go before we can truly read a person’s mind, the ability to use fMRI data to understand a person’s emotional state is a great step forward. Scientists report that they still have a lot to learn before we can apply this to very similar emotions, like fear or anxiety. Regardless, they are hopeful that this could be an important clinical tool to help people who have trouble understanding emotions.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Heads image by Matthieu James.

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Decoding Emotions in the Brain

- Author(s): Patrick McGurrin

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: 24 Oct, 2016

- Date accessed: 21 May, 2025

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/brain-emotions

APA Style

Patrick McGurrin. (Mon, 10/24/2016 - 16:44). Decoding Emotions in the Brain. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/brain-emotions

Chicago Manual of Style

Patrick McGurrin. "Decoding Emotions in the Brain". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 24 Oct 2016. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/brain-emotions

MLA 2017 Style

Patrick McGurrin. "Decoding Emotions in the Brain". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 24 Oct 2016. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/brain-emotions

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.