Illustrated by: Dr. Biology

Sea Urchin Research

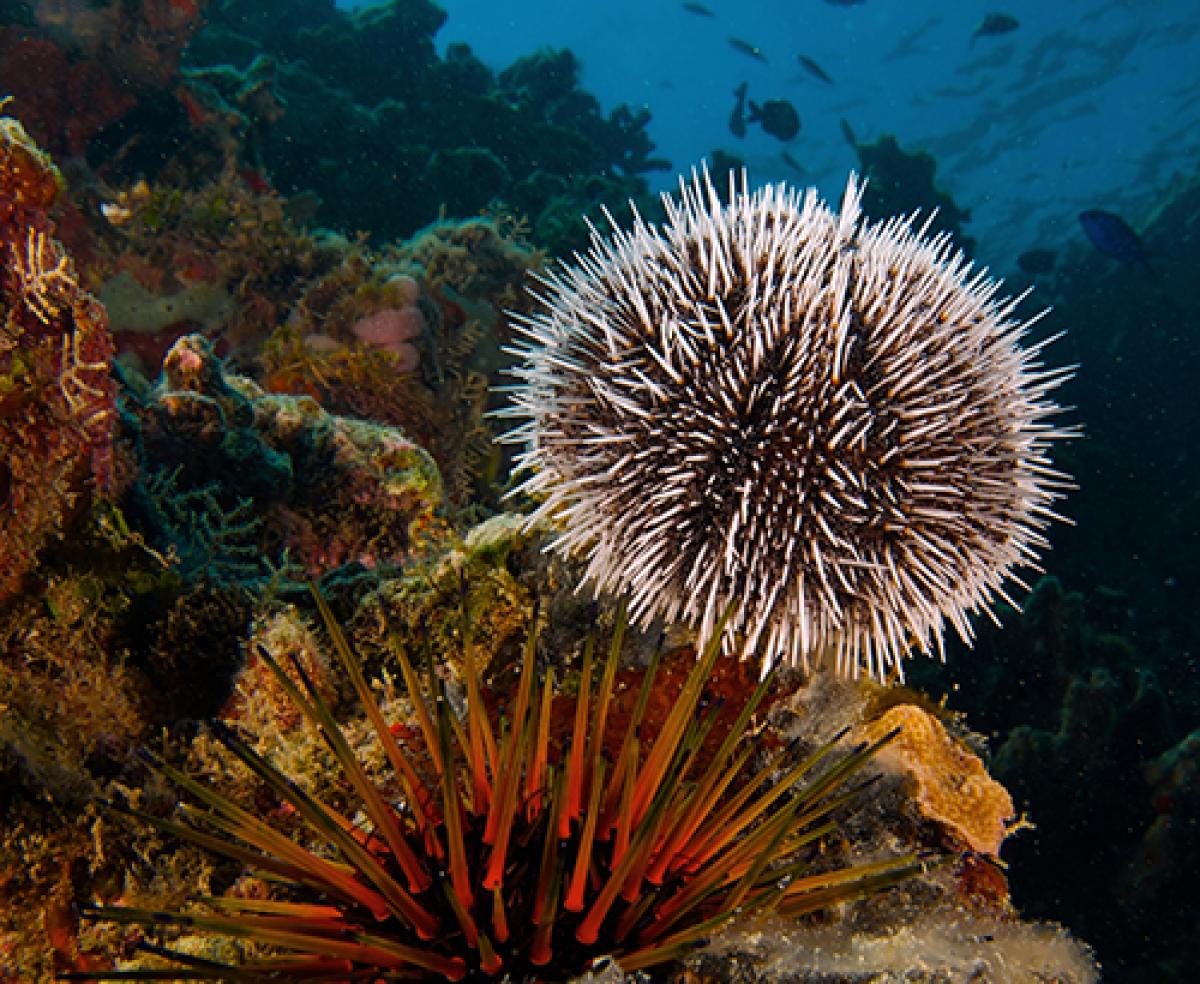

Slowly moving across the bottom of the aquarium is a dome-shaped creature, covered by what looks like thick purple toothpicks. The toothpicks are really called spines. Mixed in with the spines are long thin spaghetti-shaped tentacles that are called tube feet. Many of the tube feet look like they are dancing. They sway back and forth in the water while others, with their suction ends, grab onto rocks to help move the creature. The creature is not alone. There are others with their purple spines and suction-tipped tube feet attached to the clear sides of the aquarium. This is the world for our desert-dwelling purple urchin, Strongylocentrotus purpuratus (strong-e-low-cent-row-tus / purp-er-ot-us).

No, urchins are not indigenous to the desert. The usual home for Strongylocentrotus purpuratus is the ocean's rocky floor for grazing along the intertidal and subtidal areas. Sea urchins belong to the group called Invertebrates (which means 'animals without backbones') and to the phylum called Echinoderms, in which there are over 6000 species of animals. Echinoderms are known for their round symmetry. The symmetry most often has five equal parts, easily seen when looking at another echinoderm: the starfish and its five radial arms.

Except for their round shape, the symmetry of sea urchins are more difficult to view. It is not easy to see they have a five-point radial design that makes them pentamerous like the closely related starfish. One thing you can see with both the urchin and the starfish are their tube feet, complete with individual suction-cup ends. They use these "feet" to move. By attaching their tube feet to rocks, urchins can pull themselves along the rocky bottom of their ocean homes. A single tube foot is not enough to move an urchin, but using large numbers of its hundreds of tube feet, it can make its way along the ocean floor.

If you take a closer look at our urchin, still moving across the bottom of the aquarium, you would notice that there are two openings in its body. There is the opening on its bottom, near the ground, where the mouth is located. This area is called Aristotle's lantern, and is structure unique to echinoderms. The lantern is a complex system of small bones and muscles that surrounds the esophagus and is used to scrape algae (urchins' favorite food) off rocks during feeding. The other opening is located at the top of the urchin and is called the aboral (no mouth) end. Waste products exit the aboral end and this is also the place where eggs or sperm are secreted.

How Sea Urchins Are Used in Research

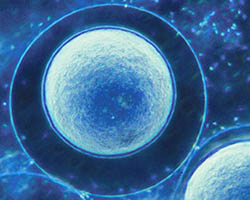

Urchins help scientists understand the mystery of animal development by helping them to answer questions about egg fertilization and embryonic development. Sea urchins have been used for many years by scientists to study developmental processes such as fertilization. Because they have lots of relatively big eggs, they're ideal animals to study. When secreted, the eggs of S. purpuratus appear orange in color. Scientists can mix the eggs from a female with the sperm from a male in sea water. Then, developmental processes such as egg and embryo development can be studied.

Read more about: Sea Urchins Do Research

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Sea Urchins Do Research

- Author(s): CJ Kazilek

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: 27 Sep, 2009

- Date accessed: 22 August, 2025

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/sea-urchins-do-research

APA Style

CJ Kazilek. (Sun, 09/27/2009 - 13:26). Sea Urchins Do Research. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/sea-urchins-do-research

Chicago Manual of Style

CJ Kazilek. "Sea Urchins Do Research". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 27 Sep 2009. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/sea-urchins-do-research

MLA 2017 Style

CJ Kazilek. "Sea Urchins Do Research". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 27 Sep 2009. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/sea-urchins-do-research

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.