Illustrated by: Sabine Deviche

A Brief History of Antibiotics

Have you ever gone to grab a piece of bread from the shelf, only to find an icky bluish-green blob growing somewhere on the crust? Your first instinct was probably to pick it up between two fingers and drop it right into the trash. That’s a reasonable thing to do.

But, if you were an ancient Egyptian, you might not be so quick to do that, especially if you or someone you knew had a nasty cut or infection. In fact, some scientists have learned that ancient civilizations in Egypt, Greece, China, and Rome used to use some pretty weird things, such as bread mold and certain dirts, to treat wounds all the time. Why would they do this?

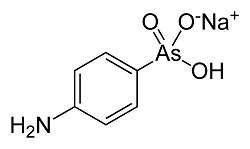

Well, the most obvious answer is that it must have worked! It wasn’t until the late 1800’s that more modern scientists started to understand exactly why things like mold and dirt were so good at healing infections. One of the most important clues was a discovery by a scientist name Paul Ehrlich. He found that when he put certain dyes into a dish of bacteria, only some of the bacteria were stained, meaning they absorbed the dye. This made him think that if he could make a chemical that acted like a dye, but also killed the bacteria, it could be very useful for treating diseases. He began his search by altering a drug that had already been used to treat some other diseases.

In his lab, he would change the molecule in different ways, and then test how well the new molecule killed off bacteria in rabbits. He tried 605 different chemical combinations before finding that one could kill the germs that caused a disease called syphilis that was common back then. This drug is considered to be an antibiotic because it works to kill or stop the growth of bacteria. Could it be that the bread molds and dirt used by ancient civilizations also contained antibiotics?

That might sound crazy at first, but an accidental contamination in the lab of another scientist, Alexander Fleming, not only showed that those ancient doctors were onto something, but also changed how scientists and doctors have approached disease treatment.

Funny Mold Juice

Alexander Fleming was a Scottish biologist who was very interested in the bacteria that causes infections. He served in the military during World War I, during which he saw many soldiers die from infections of their wounds, rather than the wounds themselves. After many years of research, trying over and over again to find a substance that could kill harmful bacteria, he decided to take a vacation. Before he left, though, he accidentally left a petri dish with bacteria in it open on his lab bench.

When he returned from his vacation, he noticed that there was some bluish-green mold (like the mold on the bread) growing in one of the petri dishes. He also noticed that the bacteria that had been growing in the petri dish would not grow near the mold. Upon noticing this, it is said that he uttered “That’s funny,” before taking samples of the mold to find out why the bacteria wouldn’t grow near it. Fleming found that the mold belonged to the species Penicillium notatum, and it produced a substance that destroyed many types of bad bacteria. This substance, which he named penicillin, was the first antibiotic produced in a living organism to be extracted and described by a scientist.

Alexander Fleming had discovered an antibiotic that would go on to change medicine forever. Still, it took about ten more years before a couple of chemists were able to extract enough of the penicillin to be useful in treating infections. Luckily, penicillin could be produced at a massive scale about the same time that the United States entered World War II, saving thousands of lives.

A Constant Chase

While penicillin is still used for some treatments today, it is not as effective against bacteria today as it was in the mid-1900’s. The reason for this is that many bacteria species have developed resistance to penicillin. In fact, many bacteria species have developed resistance to many different antibiotics, which is a huge problem for both patients and the doctors trying to treat them.

To help understand resistance, let’s imagine the following scenario: Let’s say you’ve scraped your knee, and a couple days later it’s extra swollen, red, and is itchy but painful. Your best friend suggests you go see a doctor, so you do. The doctor looks at your knee and gives you a little orange bottle of antibiotics to stop the infection.

Okay, now let’s imagine you are a bacterium. One day you are hanging out on a park bench with some of your bacteria buddies, when someone puts their hand right on top of you. They unknowingly pick you up and then scratch their knee, right next to a fresh cut. Food!! You all make your way into the cut, and begin to multiply. Soon after, a powerful antibiotic starts to kill your buddies off one by one. Luckily, you happen to have a gene that destroys the antibiotic. The other bacteria are dying, but you survive. You’ve won! Because you are the only bacteria left, you are the only one that will multiply. All of your relatives will also have the gene that destroys the antibiotic, and so now the cut is infected with a resistant strain of bacteria.

This means that that same little orange bottle of antibiotics won’t work this time. That doctor is going to have to think of a better plan in order to defeat the new infection.

In summary, antibiotic resistance occurs when some bacteria gain a gene that allows them to survive an antibiotic meant to kill them. New genes can develop in bacteria by mutation, or a gene can be transferred from one bacteria to another in a process called horizontal gene transfer. When these bacteria multiply and spread, it causes a big problem, because many people become sick. When treating an antibiotic-resistant infection, doctors must then use different antibiotics. Sometimes these other options may not work as well, or may cause bad side effects.

Antibiotics vs Bacteria: An Evolutionary Battle is sponsored by ASU's Center for Evolution and Medicine. Learn more about evolutionary medicine at isemph.org/EvMedEd.

Read more about: Antibiotics vs Bacteria: An Evolutionary Battle

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Antibiotics vs Bacteria: An Evolutionary Battle

- Author(s): Tyler Quigley

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: 10 Jul, 2017

- Date accessed: 24 July, 2025

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/antibiotics-bacteria

APA Style

Tyler Quigley. (Mon, 07/10/2017 - 15:12). Antibiotics vs Bacteria: An Evolutionary Battle. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/antibiotics-bacteria

Chicago Manual of Style

Tyler Quigley. "Antibiotics vs Bacteria: An Evolutionary Battle". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 10 Jul 2017. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/antibiotics-bacteria

MLA 2017 Style

Tyler Quigley. "Antibiotics vs Bacteria: An Evolutionary Battle". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 10 Jul 2017. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/antibiotics-bacteria

MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) is an antibiotic-resistant bacteria that infects roughly 100,000 people per year in the United States alone.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.