Illustrated by: Denise Inguito

You wake up and slowly open your eyes. An odd feeling creeps in as you look around for something—anything—that you recognize. But you don’t find anything. You’ve never been in this room before. On the nightstand, there are pictures of you with other people that you do not recognize. The clothes in the closet look like they fit you, but you do not remember ever having worn them. You wonder what you should do to get out of this strange place.

This may sound like it could be a clip from a scary movie, but this is reality for people with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s disease makes it difficult to remember many things – like where you live, the names and faces of family members, and even your own name. It’s no wonder that so many doctors and scientists dedicate their careers to curing Alzheimer’s disease. ASU professor Diego Mastroeni’s job is to study Alzheimer’s disease, and to hopefully find a way to cure it.

Alzheimer’s is More Than Just Genes

For a long time, researchers thought that Alzheimer’s disease was caused by specific genes. In more recent years, researchers have wondered if someone’s environment – where they live, what they eat, and many other things – could cause Alzheimer’s.

In one of Mastroeni’s studies, he looked at the brains of two identical (monozygotic) twins who shared almost exactly the same genes and lived almost exactly the same life. One of them contracted Alzheimer’s disease when they were old, and the other did not. If Alzheimer’s disease is only caused by genes, how could that be?

One of the main differences between the twins was where they worked. One worked in an office, and the other worked in a factory. In that factory, they were exposed to a dangerous chemical called DDT. This and other studies have led Mastroeni to believe that Alzheimer’s can be caused by the environment, and how someone’s environment interacts with their genes.

Turning Off Alzheimer’s

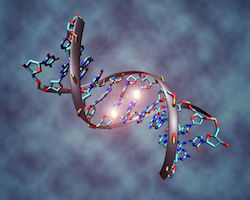

Mastroeni wanted to know more. If someone’s environment could cause Alzheimer’s disease, how does it work? To find out, he has studied neuroepigenetics, or simply put, how the genes in the brain get turned on and off. He thinks that maybe some genes are being turned on or off that could lead to Alzheimer’s.

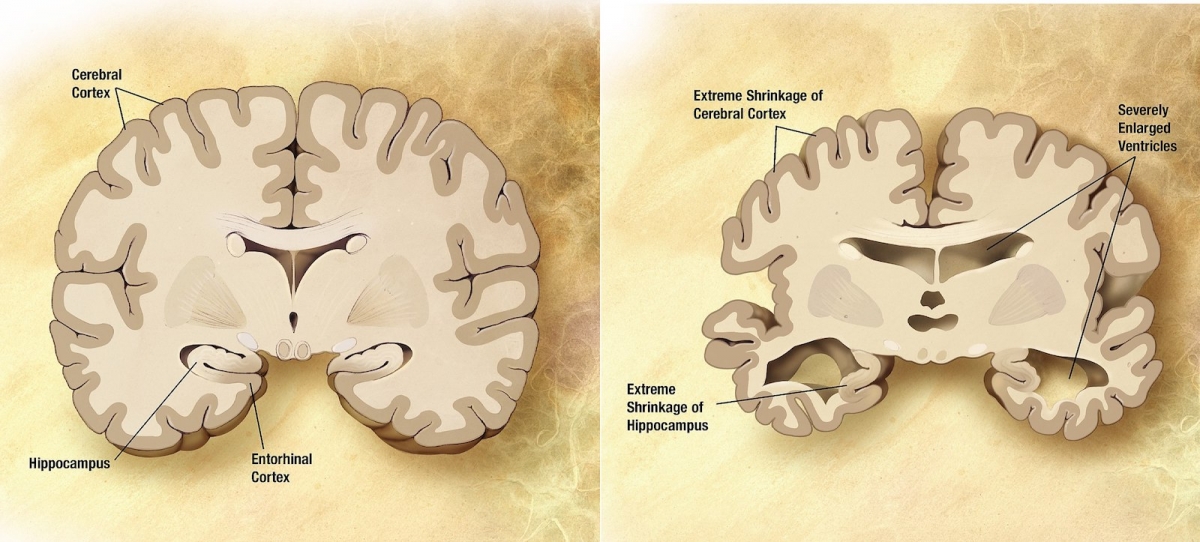

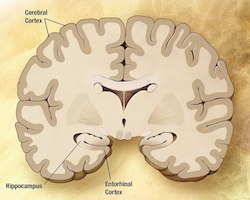

Mastroeni takes advantage of the Banner Sun Health Research “Brain Bank”, which has human brains from people who died with and without Alzheimer’s. Using these brains, he can compare the epigenetics of diseased and healthy brains. He and his colleagues have found that people with diseased brains have fewer methyl groups on their DNA, meaning more genes are turned on. This includes the gene that makes amyloid beta, a protein that builds up and causes plaques in the brain.

Growing Small Brains to Help Big Brains

Mastroeni and his colleagues have found that the number of methyl groups that are in a person’s DNA is related to whether their brain was diseased. However, without an experiment, we cannot know if DNA methylation causes Alzheimer’s. This is a big challenge for Mastroeni – he cannot possibly experiment on live humans, especially in ways that might hurt them.

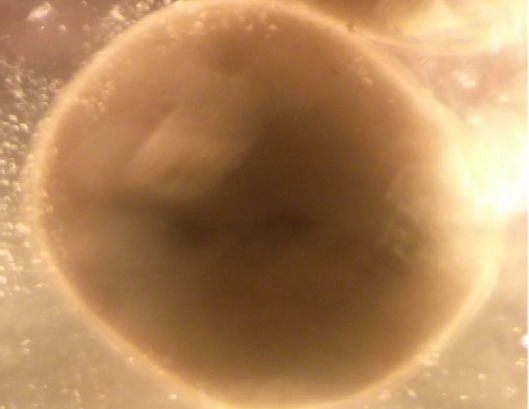

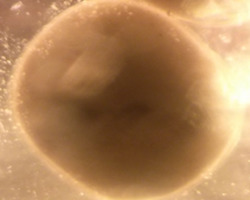

He has come up with an ingenious idea: he will study Alzheimer's on his own human brains. Based on the work developed by other researchers, Mastroeni can take stem cells from brains in the “Brain Bank”, and he can grow tiny brains in the lab. These tiny brains, called organoids, actually grow like human brains do. They grow and form the different structures that can be found in a normal human brain. Mastroeni can change the environment of the tiny organoid brains to see how it affects their DNA methylation.

For example, he could grow some brains with and without exposure to the chemical DDT to see if it actually causes Alzheimer’s disease. But he wouldn’t have to stop there. He could also find out how people can add methyl groups back onto their brain’s DNA, which could help prevent Alzheimer’s.

Thinking Ahead

One of the big problems with Alzheimer’s disease is that doctors often catch it too late. When they do, it is usually because a person is already showing signs of the disease. Mastroeni says that many signs of Alzheimer’s begin as early as someone’s 20’s or 30’s. So how can we think ahead – and catch the problem before it even begins? By studying organoid brains, he might be able to catch the earliest signs of the disease, in the form of small changes in DNA methylation.

Learning to Remember was created in collaboration with The Biodesign Institute at ASU.

Read more about: Learning to Remember

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Learning to Remember

- Author(s): Pierce Hutton

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: 1 Feb, 2018

- Date accessed: 18 May, 2025

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/meet-our-biologists/learning-remember

APA Style

Pierce Hutton. (Thu, 02/01/2018 - 17:36). Learning to Remember. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/meet-our-biologists/learning-remember

Chicago Manual of Style

Pierce Hutton. "Learning to Remember". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 01 Feb 2018. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/meet-our-biologists/learning-remember

MLA 2017 Style

Pierce Hutton. "Learning to Remember". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 01 Feb 2018. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/meet-our-biologists/learning-remember

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.