The Endless Blue

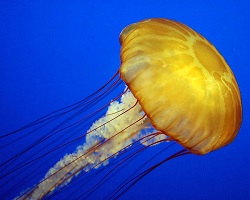

As a creature in the open ocean biome, you have two options to survive. One way is to float along on the currents and wait for food to drift by, saving energy as you go. Many jellyfish and their cousins travel by riding the waves and currents of the ocean to find new areas of food.

Another way is to constantly be on the move, quickly covering the ocean expanses to find enough food so you don't starve. Whales, sea turtles, and tuna can cross thousands of miles each year in search of food. These may seem like limited choices. However, despite how huge the open ocean biome is, food is relatively hard to find.

Even though the open ocean biome takes up a large area and has plenty of light in some places, it is relatively barren. This is because the water is low in nutrients and there is little or no structure. Whenever nutrients are blown out to sea or creatures like whales die, surface dwellers are quick to eat it up before the food sinks. If they don’t, it will quickly fall to the bottom of the ocean.

For life on the ocean floor, these sunken meals are feasts. A dead whale can provide food to crabs, hagfish, rattail fish, and sleeper sharks for years. When all the tasty meat is gone, the whale’s bones still provide food for worms and bacteria, which are fed on by other deep-sea creatures. These dead whales and the community of animals that depend on them are called whale falls.

Crossing Boundaries

Some animals are able to cross between the two depth zones to search for food. The sperm whale and Southern elephant seal are able to dive into the aphotic zone to hunt, even though the intense water pressure squishes their bodies.

Also, every night after the sun goes down, millions of hungry mouths swarm up from the depths to feed on the organisms peacefully floating in the warm epipelagic zone. Many copepods and invertebrate larvae come up to shallower waters to eat the phytoplankton, which attracts many predators like squid, hatchet fish, and lantern fish.

Many animals that migrate between the depth zones can create their own light, called bioluminescence. This nightly vertical migration is the largest migration (in terms of number of animals) on our planet.

Much like food, it's also hard to find shelter and hiding places in the open ocean. Something as simple as a floating leaf or floating garbage can attract a whole community of ocean dwellers. This debris serves as a landmark and a home in the endless blue of the ocean. Often, this debris can be dangerous for many fish, turtles, or other creatures if they get caught in it.

But before long, these temporary rafts sink into the depths too, and it is time for their residents to find a new home.

Sea Highways

Ocean currents also serve as sea highways, helping to move migrating species around ocean basins quickly in search of their next meal. Many ocean species (especially large ones like whales, sharks, and sea turtles) follow ocean currents to and from their feeding and breeding grounds.

Often you will find other creatures following these living landmarks around the ocean. Other species hitch a ride on these swimming dinner buffets. They do this in part for protection. But they can also cling to the skin to ensure they are always around to gobble up scraps, dead skin, and sometimes even the flesh and blood of their gracious host.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Krill image by Uwe Kils.

Read more about: Observing the Open Ocean

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Animals of the Open Ocean

- Author(s): Dr. Biology

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/animals-open-ocean

APA Style

Dr. Biology. (). Animals of the Open Ocean. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/animals-open-ocean

Chicago Manual of Style

Dr. Biology. "Animals of the Open Ocean". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/animals-open-ocean

Dr. Biology. "Animals of the Open Ocean". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/animals-open-ocean

MLA 2017 Style

Small shrimp-like animals called krill are an important food source in the oceans. Some large whales even depend on these tiny creatures as a major food source.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.