Honey and the Hive

A single honey bee forager will only collect up to 100 mgs of nectar—about the size of two drops of water—per trip. What do bees do with all that nectar? They make honey. Worker bees inside the hive dehydrate, or remove the water, from nectar and add gland secretions to break down some of the sugars and help preserve the honey for long-term storage.

Honey bees make large quantities of honey. It is not easy work. By the end of summer a large colony will have stored over 100 lbs, or 45 kgs, of honey to ensure the colony has enough food for the winter. You can imagine why it is so busy at a bee hive—their winter survival depends on it.

Not all species of bee have help from thousands of family members. Some bees, like digger bees, have to do all of the work of collecting food, building a nest, and rearing offspring all by themselves. Other species of bees live in small groups and recruit the help of their daughters during parts of the year. For example bumblebee colonies start with a single bee each year and then build up to a few hundred by the summer. Keep an eye out the next time you stop by some flowers and see how many species of bee you can find.

Defending the Bee Colony

As you might imagine having all that honey and resources will make you a target. Honey bees have to be ready to defend their stash of honey from any honey-loving bears, badgers, or other large animals that might want to satisfy their sweet tooth.

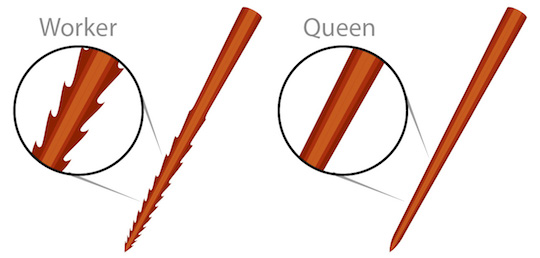

How do bees do this? They usually do not bite. Instead they sting. Honey bee workers will sting to protect their sisters and colony from danger. Honey bee worker stingers are barbed. These barbs allows the stinger to remain in the victim and continue to pump venom at the site of the sting. However this barb also means the stinging bee will likely damage its body and internal organs and later die.

Some bees, such as the giant honeybees of Asia, have many defenses, including large stinging swarms and the ability to heat up their abdomens to a temperature that will kill smaller predators, like a wasp.

European honey bees are not the only bees that need to defend their colonies. Not all bees even have stingers. Bee keepers in the tropics often keep stingless honey bees. Don’t let their name fool you though; stingless honey bees bite to defend their colony.

Africanized Honey Bees

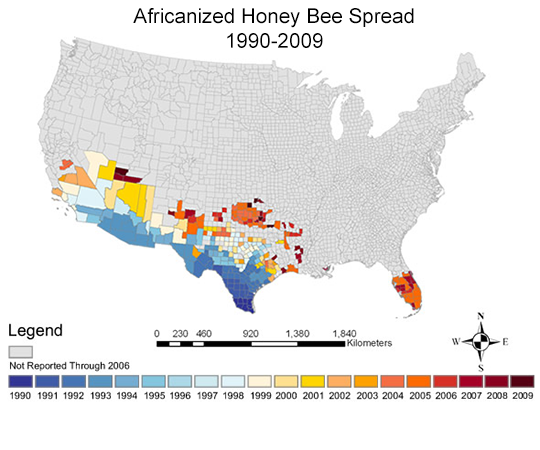

Africanized honey bees are a hybrid of honey bees native to Europe and honey bees native to southern Africa. The Africanized honey bees are more willing to nest in open spaces and the queens develop and swarm a bit faster. Both of these factors allowed them to quickly spread through South America and the Southern portions of North America.

The thing Africanized bees are most known for is their sting. But the sting is no different than a European honey bee. Africanized bees are only a bit more sensitive to the signals bees use to trigger a defense or sting response. This means they are quicker and more likely to sting, and that is what makes them more dangerous to be around. However like the European honey bee they are only defensive at their nest.

As long as you stay away from the nest and do not bother the bee, you are fine to observe Africanized honey bees collecting pollen and nectar just like any other bee.

Read more about: Bee Bonanza

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Honey and the Hive

- Author(s): Dr. Biology

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/bee-honey

APA Style

Dr. Biology. (). Honey and the Hive. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/bee-honey

Chicago Manual of Style

Dr. Biology. "Honey and the Hive". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/bee-honey

Dr. Biology. "Honey and the Hive". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/bee-honey

MLA 2017 Style

How much work do bees have to do to get that sweet honey we all love? Image by CJ Kazilek.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.