Summarizing Sex Traits

Illustrated by: Sabine Deviche

Sarah’s parents are exhausted after spending all morning teaching her how to bake. First, they had to teach her to read the recipe, and then they made sure she put all the ingredients into her cookie mix at the right time. But now, the cookies are about to come out of the oven.

The timer goes off and Sarah jumps up and down shouting, “They’re done! They’re done!” as she watches her mom pull the cookies from the oven. Sarah’s mom sets the cookies down on the counter, and Sarah gazes at them hungrily.

She notices that some of the cookies look very different from one another. The lemon cookies look much more yellow than the pale sugar cookies. Sarah asks her parents why they look that way.

Her parents remind her that they used unique recipes and ingredients for each type of cookie they made. That’s why the lemon and sugar cookies taste and look different.

In fact, humans look different from each other for a similar reason. Our looks can differ greatly based on our “recipe,” or DNA. A major part of that recipe has to do with our biological sex. All people have a lot of similar DNA, but males and females tend to have one important difference: their sex chromosomes. A small change in a person's sex chromosomes can lead to bigger changes in their body parts. People of the same biological sex tend to have lots of similar DNA. That's why they often grow similar traits and body parts.

A Distinct Difference

The most obvious difference between the lemon and the sugar cookies is that the lemon cookies are more yellow. There is also one main traits that people use to tell biological sexes apart: our sex organs. Sex organs are the body parts that humans use to reproduce, or to have children. The sex organs and other body parts we have are decided by our sex chromosomes.

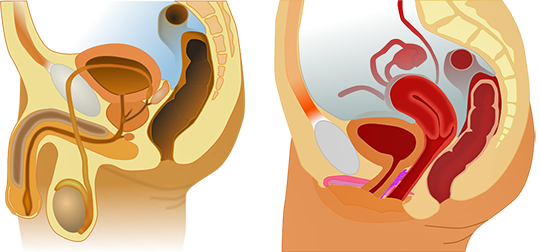

The main male sex organ is called a penis while the main female sex organ is called a vagina. However, these are just the outside parts of human reproductive systems. Other parts of the typical male reproductive system include the testes and the prostate. Testes produce sperm. The prostate produces fluid that combines with sperm to make semen, the liquid that comes out of the penis after sexual climax. Most females have ovaries, a uterus, and a vagina. Ovaries make eggs, a uterus carries a growing fetus, and a vagina is a tube made of muscle that connects the uterus to the outside of the body.

While these main sex organs shape our bodies in certain ways, our sex and gender are also shaped by many other things. For starters, we also have plenty of secondary sex traits.

Seeing the Secondary

Other than just the color, Sarah notices other less obvious differences between the lemon and sugar cookies. The sugar cookies are soft and moist, while the lemon cookies are thinner and crunchier.

Across biological sexes, people also have many differences other than their sex organs. Some of those differences that still relate to sex are our secondary sex traits.

Some secondary sex traits that are more common in women are breasts, wider hips, and thicker hair on their head. Some male secondary sex traits are facial and chest hair and deeper voices.

Not every person has these traits. Women can have facial hair or deeper voices and still be just as much of a woman as anyone else. That might happen as a result of a difference in sex hormones, for example. Even though our biological sex can affect how we look, there is no right way for a person to look.

Plenty of Possibility

After gobbling up her cookies, Sarah asks her parents “Can we make different kinds of cookies tomorrow? Maybe peanut butter cookies, or snickerdoodles or chocolate chip!”

“Don’t worry, we’ll make all kinds of cookies soon,” they smile.

Like Sarah’s cookies, there are also more than just two kinds of biological sexes that humans can have. There are many intersex people who are neither strictly male nor female. Intersex people often have a combination of typical male or female body parts at the same time.

Also, many people are assigned a certain gender based on their biological sex at birth but do not identify as that gender as they grow older. Many people who fit this description are called transgender. Some transgender people undergo surgeries so their body parts match their gender identities.

But, many transgender people do not get those surgeries. A person does not have to have surgery to identify as a gender that differs from their sex at birth. For example, a person who identifies as female could have male or female genitals, and vice versa. Our gender identities depend on a lot more than our body parts.

In Trouble for Talking

It doesn't take a scientist to see differences between sexes because many of the differences are obvious. However, it took a long time for people to get comfortable talking about sex and our bodies.

One of the first people to openly talk about sex and our bodies was Margaret Sanger. Sanger was a women’s rights activist in the US in the early 1900s. She published a book called What Every Mother Should Know in 1914 and a book called What Every Girl Should Know in 1916. Those books detail changes that young people undergo as they grow; the books also give advice for young people to stay sexually healthy and take care of their bodies.

Not everyone was happy that Sanger was talking about these topics openly. Sanger got in trouble for mailing material through the post office that was thought of as offensive. The Post Office Department threatened to block Sanger’s work from being sent out. Luckily, Sanger’s book was still published, as its main goal was to be informative, and many people read it.

Speaking of Sex

In 1919, another activist Mary Ware Dennett published a pamphlet called The Sex Side of Life. The Sex Side of Life talks about what sex organs do, the roles of love and pleasure in sex, and sexual processes that happen in the body. At the time, people did not openly talk about sexual matters.

Like Sanger, Dennett also got in trouble, and was taken to the Supreme Court for publishing obscene content. Dennett won her court case because she was only wanting to educate people. Her win helped more people talk about sex and helped reduce the stigma around sex education.

Much later, by the 1970s, discussing bodies and sexual topics was no longer illegal, but was still not common. In 1973, a group of women in Boston wrote and published a book called Our Bodies, Ourselves. The book gave women true information about their bodies and sexual health care. It covered lots of topics, from knowing how women’s bodies change during menopause to advising women on how to talk to their doctors. Our Bodies, Ourselves was a very successful book. New editions were written up until the 2000s, with new information added into each edition.

Today, most schools have a sex education course for young people to learn about these topics openly. Still, people continue to disagree about the best way to talk about sex and bodies with young people.

Human embryo image by Ed Uthman via Wikimedia Commons.

This Embryo Tale was edited by Dina Ziganshina and is based on the following Embryo Project articles:

Drago, Mary, "Hermaphrodites and the Medical Invention of Sex (1998), by Alice Domurat Dreger". Embryo Project Encyclopedia (2014-04-09). ISSN: 1940-5030 http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/7818.

Malladi, Lakshmeeramya, "The Sex Side of Life (1919) by Mary Ware Dennett". Embryo Project Encyclopedia (2017-05-27). ISSN: 1940-5030 http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/11524.

Malladi, Lakshmeeramya, "What Every Girl Should Know (1916), by Margaret Sanger". Embryo Project Encyclopedia (2017-12-12). ISSN: 1940-5030 http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/13024.

Malladi, Lakshmeeramya, "What Every Mother Should Know (1916), by Margaret Sanger". Embryo Project Encyclopedia (2017-10-24). ISSN: 1940-5030 http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/13003.

Pingolt, Maggie. “Our Bodies, Ourselves (1973), by the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective.” Embryo Project Encyclopedia (2013-06-21). ISSN: 1940-5030 http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/5908.

Read more about: Summarizing Sex Traits

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Summarizing Sex Traits

- Author(s): Risa Aria Schnebly

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/embryo-tales/sex-characteristics

APA Style

Risa Aria Schnebly. (). Summarizing Sex Traits. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/embryo-tales/sex-characteristics

Chicago Manual of Style

Risa Aria Schnebly. "Summarizing Sex Traits". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/embryo-tales/sex-characteristics

Risa Aria Schnebly. "Summarizing Sex Traits". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/embryo-tales/sex-characteristics

MLA 2017 Style

In Ancient Greece, Aristotle thought that all embryos were meant to grow into males. But if embryos didn't have enough heat, he thought, they wouldn't grow all the way, and they would be stuck as females. Now, we know that no embryos are "meant" to become male. We get our sex traits from DNA and other factors–in humans, heat has nothing to do with it!

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.