Larval Beetles Spin Their Wheels on the Beach

What's in the Story?

We take wheels for granted because they are everywhere and easy to ignore. But we depend on them almost every day. Wheels in nature are not as common. It is next to impossible to have blood veins and nerves connect to something that is rotating.

When faced with danger, it jumps out of its hole, coils its body into a circle, and hits the sand rolling. It uses the wind, usually coming strongly off the ocean, to drive it at great speed up the beach and uphill into the dunes. This rolling motion is as close to a wheel as we can find in nature.

Tiger Beetle Larvae

The short-legged, white larval tiger beetle spends most of its time in a long tunnel dug deep down into the sandy ocean beaches of the east coast.

When it is too cold, rainy, or hot, the larva moves down to the bottom of the tunnel for protection. When the air temperature and weather are sunny and warm, the larva uses its short legs and funny hooks on its back to climb back up to the opening of its tunnel.

If the larval tiger beetle can eat lots of food every day during the summer, it will grow up, change its body, and become an adult running quickly across the sand on long beautiful legs and flying short distances on clear wings.

Enemy Wasps

But the protection of the tunnel is not always good enough. For example, when a certain species of wingless wasp approaches. This wasp spends its whole life hunting for larval tiger beetles, paralyzing them and then laying eggs on the tiger beetle. The young wasps hatch out and eat the tiger beetle.

You would think that there would be no hope for the poor tiger beetle larva. Even if they recognized the female wasp as it approached the tunnel opening, the larval tiger beetle is not built for rapid escape.

If it ducks down into the tunnel, the wasp follows it. If the larval tiger beetle escapes from its tunnel and tries to wiggle away, its fat body and short legs mean it won’t get far.

Escape from the Wasp

Luckily the larvae of the Eastern Beach Tiger Beetle may have solved the problem with the near-impossible trick of becoming a wheel. As soon as a wasp approaches, the larval tiger beetle could jump out of its hole, coil its body backwards, and spring high into the air. There it can fold forward into a circle and hit the sand rolling. It can use the wind, usually coming strongly off the ocean, to drive it at great speed up the beach.

How to Measure Wheeling Tiger Beetles

The scientists who discovered this wheeling behavior in larval tiger beetles did so by chance. They were on the beach moving around some odd sand piles when they started noticing a blurry wheel quickly rolling away every once in a while. It was so fast the scientists were not sure what it was. They had to follow one of these blurs until it stopped and unrolled.

Over two summers, scientists returned to measure the behavior of this larva. They wanted to know what caused the larva to roll, if anything controlled the direction it rolled, and how fast it rolled. The scientists measured the direction and speed of the wind over the beach with weather equipment. They compared two neighboring areas of beach. One area was smooth and the other had been roughed up with foot prints of human beach traffic.

To do their tests, scientists carefully dug tiger beetle larvae from their tunnels in the upper beach. Each larva was only used once. It was placed on the sand surface of one of the beach types and gently touched with a small twig until it reacted. The scientists used video cameras to record the reaction of each larva. The videos could then be replayed over and over again in the lab to see exactly what the larvae were doing on different sand surfaces and with different wind direction and speed. The scientists also measured how far the larvae moved.

Larval Reactions

If the larvae were touched on the front part of their bodies, they usually jerked or crawled away. Sometimes they opened their mandibles wide open to try to try to bite their attackers (or at least scare them away), and other times they pretended they were dying or dead.

However, when the larvae were touched near their tails or back parts of the body they reacted by jumping up into the air by pushing off with their tails. If the wind was weak they would flatten out and fall back to the sand. If the winds were stronger than about 10 ft/sec (3 m/sec) the larvae would stay coiled in a circle and wheel with the wind.

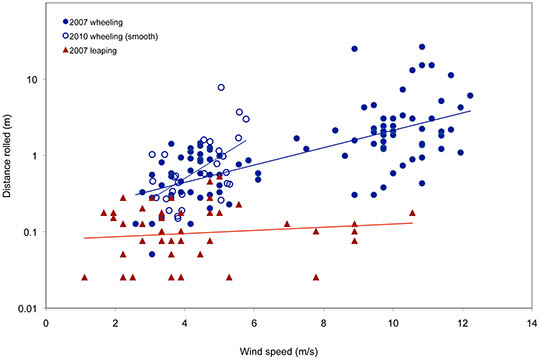

Scientists found that wheeling larvae can reach speeds of 10 feet/sec (3.3 m/ sec), faster than you or I can run in the sand and certainly much faster than the female wasps. And they can wheel for more than 200 ft (60 m) (Graph 1). The faster the wind, the faster and farther the larvae rolled. Larvae also followed the direction of the wind and went much farther on smooth sand. Even small patches of surface roughness, like human foot prints, could slow or stop the wheeling behavior.

Human Dangers for the Tiger Beetle

If you watch these beetles in slow motion, you can really see what is happening. If the wheeling beetle runs into some deep tracks in the sand, say from a jeep, its escape can be jeopardized. Humans often don't realize what a large effect they can have on a habitat. Someone walking on the beach could leave tracks that stop the escape of a wheeling tiger beetle. Even if we mean the tiger beetle no harm, we sometimes do things that make some habitats more dangerous for the animals and plants that live there.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Wheeled animal sculpture by Daderot. Indonesian bike by Jonathan McIntosh via Wikimedia Commons.

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Larval Beetles Spin Their Wheels on the Beach

- Author(s): David L. Pearson

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/larval-beetles-spin

APA Style

David L. Pearson. (). Larval Beetles Spin Their Wheels on the Beach. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/larval-beetles-spin

Chicago Manual of Style

David L. Pearson. "Larval Beetles Spin Their Wheels on the Beach". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/larval-beetles-spin

David L. Pearson. "Larval Beetles Spin Their Wheels on the Beach". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/larval-beetles-spin

MLA 2017 Style

Want to learn more about tiger beetles? Visit our story on Tough, Tiny Tiger Beetles.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.