Of Mice and Men: Using Mice to Study Human Brains

What's in the Story?

Imagine that you are a scientist who studies the brain. One morning, your cousin comes to visit you. She looks exhausted and she keeps complaining that she has a mysterious headache. You encourage her to visit her doctor. After running some tests they find that she has a rare brain disease. Her doctor says that soon she may have seizures, or even fall into a coma. You decide to try to find the cure in time to help your cousin. But how?

Finding the cure for a brain disease is a lot of work. You will need to do many, many experiments to find the right medicine. This is even harder because experiments that involve the human brain can be very difficult. They can also be dangerous. Because of this, scientists often perform experiments using mice. Mice are also easier to study than humans.

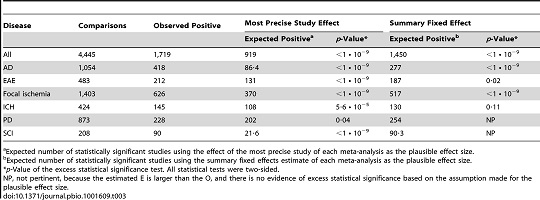

Can you use a mouse to find a cure for a human? In the PLOS Biology article, “Evaluation of Excess Significance Bias in Animal Studies of Neurological Diseases,” scientists write about some of the mistakes that can happen when using animals to study humans.

Starting with Mice

Because you're eager to find a cure for your sick cousin, you apply to the animal research committee at your university and you start a pilot study with 10 mice. It just so happens that there is a brain disease similar to the one that your cousin has, except that it affects mice. If you can find a medicine that cures the mice, there’s a chance it will cure humans, too.

Scientists who work with animals are able to do experiments that wouldn’t be allowed with humans. They take extra steps to make sure they don't needlessly hurt animals, but sometimes research can be painful for the animals involved, or the animals might die.

So why do the research at all? Animal research has helped scientists to find treatments for many diseases in humans. Many scientists must balance the possibility of hurting or sacrificing animals in their research with the potential benefits to humans.

In this example, you decide to give all of your mice the brain disease. Five of the mice receive the new medicine. The other 5 don't receive the medicine. This second group of mice is your control group. They show what happens when no treatment is given. Ten days later, you count your mice. 4 out of the 5 mice that received medicine are cured, while every single one of the control mice has died. You perform more extensive studies on mice and find the same results. Based on your results, the new medicine could be the cure.

Mice Are Not Like Humans

You rush to have the same medicine made for people, and you start testing it on patients as soon as possible. But for some reason, the medicine doesn’t work on people. The patients report that they don’t feel better, and they start to get strange stomach aches. You go back to your lab, disappointed and confused. You really wanted to help your cousin, and you were so sure you found the cure when most of the mice got better. What went wrong?

Scientists who use animals to study brain diseases often think that their cures work better than they really do. In this study, researchers looked at the results of 4,445 different scientific experiments by scientists who study the brain. The researchers counted how many of those scientists said that they found cures that worked in animals, and found that a lot more scientists thought they found cures than could possibly be true.

The Problem with "Cures"

There are three big reasons why it might look like scientists find more cures than they really do.

First of all, sometimes statistics make things sound better than they really are. Statistics are the numbers that you use to talk about or compare your scientific results. In your first experiment, 4 out of 5 mice were cured. You could also say that 80% of your mice were cured (4 is 80% of 5), or that out of all of the mice only 1 wasn’t cured. Which one of those statements sounds most impressive? Sometimes statistics can make an experiment sound more successful than it really was.

On top of that, statistics that show an experiment didn't work might not get as much attention. When you don't find a cure right away, you might just want to move on to your next experiment, but if you think you found a cure, you probably can't wait to tell people about your results! Experiments that seem to find cures are exciting, so scientists are more likely to turn their most successful results into articles that other people can read.

Second, the experiment might not be set up properly. When you go back and look over your results, you realize that when you sorted the mice, the 5 that you gave medicine to were younger and healthier than the control mice in the first place, just by chance. They probably did better than the mice without medicine just because they were healthier from the start. For your next round of experiments, you would want to use more mice and pick mice that are all the same age and have similar health.

Third, mice aren’t exactly like humans, and they can’t talk to us. Just because a medicine can cure a brain disease in mice doesn't mean that it will cure it in humans. There might also be unpleasant side-effects that the mice can't tell us about. Remember those strange stomach aches that your patients were having? Scientists must be careful not to assume that what works for an animal will always work for humans, too.

Finding cures for brain diseases is a very important job. Many scientists have friends or relatives with diseases. That makes them passionate about finding cures.

No matter how much scientists want their treatments to work, they need to set up experiments carefully so that they can be confident about the results. Studying how scientists do their work is important because it helps them to avoid problems and design better experiments. That way, we'll find real cures faster. That's something we can all be happy about.

To learn more about the importance of and regulations guiding animal research, visit Using Animals in Research.Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Colorful MRI by Nevit Dilmen. Thumbnail by David Liao. Lab mouse in gold box by Rama.

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Of Mice and Men: Using Mice to Study Human Brains

- Author(s): Anika Larson

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/mice-and-men

APA Style

Anika Larson. (). Of Mice and Men: Using Mice to Study Human Brains. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/mice-and-men

Chicago Manual of Style

Anika Larson. "Of Mice and Men: Using Mice to Study Human Brains". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/mice-and-men

Anika Larson. "Of Mice and Men: Using Mice to Study Human Brains". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/mice-and-men

MLA 2017 Style

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.