Mischievous Microbes

What's in the Story?

It’s time for dessert, and sitting in front of you is a delicious cream tart covered in fruit. You dig a spoon into the fruit and take a bite. As you chew, your body starts to break it down. You swallow, and as it moves through your digestive tract, your body absorbs energy from it. But you are not alone. Your gut is like a big house, for billions of bacteria. When you eat, they do too. These bacteria form your microbiome.

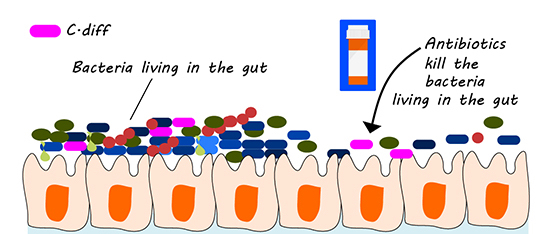

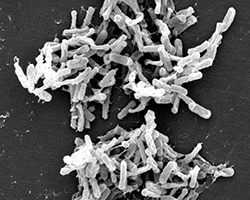

Among these bacteria, there's a type called Clostridioides difficile. Previously the name was Clostridium difficile, but for either version, it's often just called C. diff.C. diff is what is known as an opportunistic pathogen. When many different bacteria live in our guts, they keep C. diff from doing harm. But when healthy bacteria are missing, the C. diff become mischievous. They start producing toxins that can harm us.

In the PLOS Pathogens article “Para-cresol production by Clostridium difficile affects microbial diversity and membrane integrity of Gram-negative bacteria,” scientists try to understand what mischievous C. diff do in the gut.

The Benefits of Your Microbiome

So, why doesn’t your body fight off these gut bacteria? Because you actually need them. They help break down the food you eat. When you munch an apple, some of the microbes in your gut will use parts of it, too. Then, they are master chefs, cooking up essential molecules for you. These bacteria also help keep other germs away. In short, you need them to live.

Your microbiome holds billions of different bacteria, viruses, and fungi. These microbes don’t all eat the same thing. Some prefer to get energy from protein-rich foods like meat or fish, while others get energy from veggies. Healthy guts have many different types of bacteria, but it isn’t always easy to keep all those bacteria around.

The microbiome is important, but it is also sensitive to changes. One group of molecules that can change it is antibiotics. These drugs are used to help kill bad bacteria that make you sick.

Sadly, antibiotics are not great for our microbiomes. It's like using a cleaning disinfectant—it will wipe out the bad germs in the house, but the good ones too. But some bacteria can resist these antibiotics, including our mischievous C. diff.

How Does C. diff Resist Antibiotics?

There are some ways C. diff can survive antibiotic treatment. Some may have special mutations that give them protective traits. But other C. diff may form special small cells known as spores. Spores have a resistant cover that protects them from many things, including cold, pressure, and antibiotics.

Antibiotics are great for resistant C. diff. They kill off other bacteria that fight with C. diff for space, but they don’t kill the resistant C. diff or their spores. Once the protective bacteria have been killed off, C. diff can grow more easily. The spores will switch on a process called germination. They become normal cells again and eat all the food in the house.

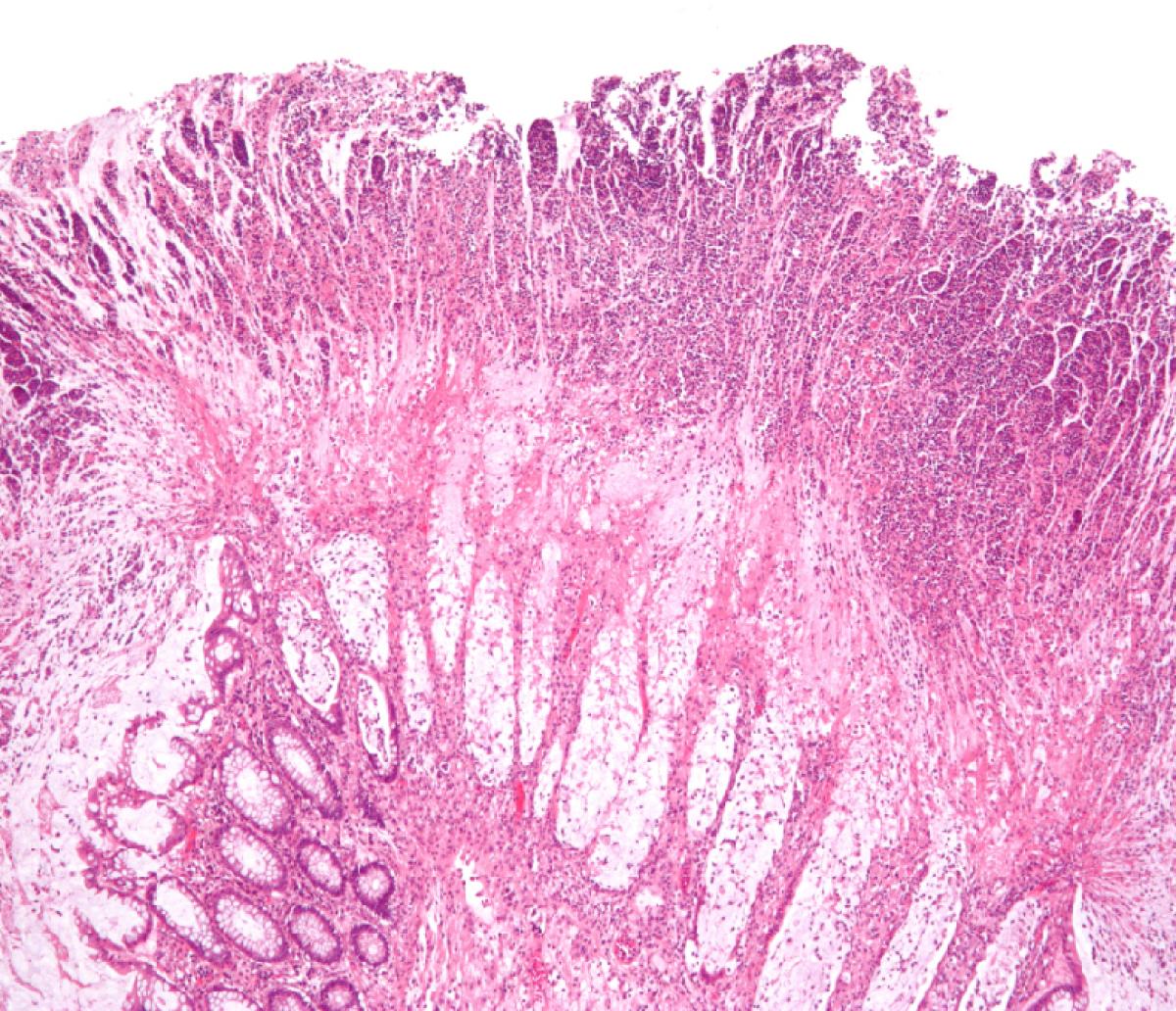

Because C. diff only takes over and tries to invade the intestines when other bacteria are missing, we call it opportunistic. When it takes over, it can do a lot of harm to our bodies. It produces toxins, which harm the lining of our guts and can lead to colitis.

What Else Can C. diff Do?

In general, microbes are good at changing one molecule into other molecules. C. diff does the same. It eats its food (especially amino acids) and spits out other molecules. One of them is para-cresol.

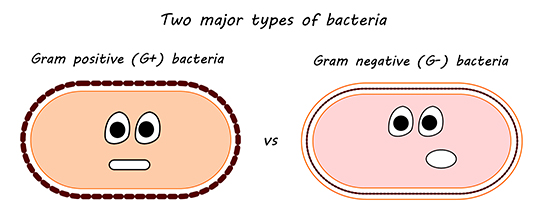

The tiny molecule para-cresol is bad for some microbes. When taken up by some bacteria, it stops them from growing. Scientists think this might have to do with their bacterial cell wall. So let’s look at the bacterial cell wall in a bit more detail.

The Bacterial Cell Wall

Bacteria can be separated into two main groups based on their outer coverings. Gram positive (G+) bacteria have a thick coat, while Gram negative (G-) bacteria have a thinner coat with multiple layers. Having a different outer shell means having different properties. Because of this, G+ and G- aren’t protected against all the same things. So, scientists wanted to look at the effects of para-cresol on these two types of bacteria.

The Effect of para-Cresol on Microbes

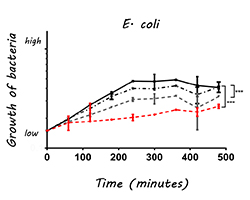

To test this, they grew different microbes (both G+ and G-) in tubes with food. Then, they added para-cresol to this mixture to see how it affected the bacteria. They checked the growth of bacteria by measuring how many bacteria were present in part of the tube. Using this measure of the density of bacteria, they then estimated the total bacteria present. If the bacteria grew as quickly as normal, then the para-cresol didn’t have an effect. But, if the special molecule was bad for the microbe, the number of cells would increase very little or not at all.

G+ bacteria like C. diff and others did not have problems because of para-cresol. But some bacteria, like E.coli, grew less well with added para-cresol.

What Happens Inside the Gut?

In many experiments, scientists use mice to represent humans. Like our microbiome, mice can also have about a billion bacteria in their guts. The scientists wanted to imitate the guts of people with colitis (the deadly disease caused by C. diff), so they gave the mice two treatments of antibiotics. For 12 days, the first antibiotic wiped out most of the mice’s microbes. Then the scientists fed the mice C. diff spores (with resistant covers).

For the next 21 days, the mice received no more antibiotics. This allowed C. diff and other microbes to grow back. Then the scientists treated the mice with another antibiotic for 7 more days. This antibiotic killed C. diff and the healthy good bacteria. After this treatment, C. diff were in a race with the heathy bacteria to see who could grow the quickest. C. diff won the race and caused disease.

After the treatments, scientists noted some changes in the mouse microbiome. Bacteria belonging to the G+ group (with a thicker coat) were more abundant than bacteria in the G- group. This meant that C. diff changed the mouse microbiome. Most likely, it was because C. diff produced para-cresol, as G- bacteria are more sensitive to para-cresol than G+ bacteria.

The Fight Against C. diff

When you take the antibiotics your doctor prescribes, countless microbes in your body die. If, by chance, C. diff is present and survives, it can go from being harmless to being dangerous for you. It is good at making new molecules, like para-cresol, that can reduce the growth of other bacteria. But it can also produce toxins that could hurt cells that line the gut.

Keeping a Healthy Microbiome

We are still learning about the best ways to keep your microbiome healthy. Antibiotics are important, and can save lives, but they target good bacteria as well as bad. One thing we know for sure about the microbiome is that eating foods filled with vitamins and minerals helps to grow a healthy microbiome. And by keeping your microbiome healthy, you might be able to keep C. diff from trying to take over.

Illustrations by Gayetri Ramachandran. Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Colitis membrane image by Nephron.

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Mischievous Microbes

- Author(s): Gayetri Ramachandran

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/mischievous-microbes

APA Style

Gayetri Ramachandran. (). Mischievous Microbes. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/mischievous-microbes

Chicago Manual of Style

Gayetri Ramachandran. "Mischievous Microbes". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/mischievous-microbes

Gayetri Ramachandran. "Mischievous Microbes". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/mischievous-microbes

MLA 2017 Style

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.