Illustrated by: Sabine Deviche

When you picture a desert, you may think of heat, sand, and a lot of empty space. While this can oftentimes describe a desert, it doesn’t always. As an example, think about the continent of Antarctica.

Antarctica is covered in ice and has minimum temperatures that reach below a chilling -80˚C (-112˚F). But Antarctica receives very little rain and snow, which makes it a desert. The low amount of rain or other precipitation that falls from the clouds, like snow or sleet, is often what defines a desert.

Most deserts get less than 20 inches of precipitation per year. But some deserts, like the Atacama Desert of South America, get almost no rain at all. So how come some biomes, like tropical rainforests, get so much water, while deserts get very little water? Or to think of it another way, what locations and conditions can create a desert?

One main thing that affects where deserts occur is a physical property of air—it can hold more water when it is warmer.

Drying Deserts with Air

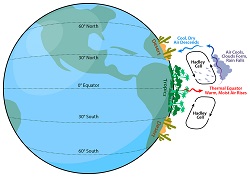

Deserts cover around 20% of the Earth and are on every continent. They are mainly found around 30 to 50 degrees latitude, called the mid-latitudes. These areas are about halfway between the equator and the north and south poles.

Remember that moist, hot air always rises from the equator. As this air climbs higher in the sky, it cools. Cool air can hold less water than warm air. This means that as the air cools, clouds form that release most of the water they hold. Because the cooling air is above the equator, the moisture rains back down on the tropics.

As warm air keeps rising from the equator, it pushes the cooler air away. The cool air moves north and south before falling back toward the ground at around 30 to 50 degrees north and south of the equator.

With warm air rising above the equator and the cooled air falling to the north and south, two circular patterns of air movement are created around the equator. These patterns of air circulation are called Hadley cells.

When the cool air begins to fall back toward the ground, or descend, it starts to warm up again. This warm, dry air can hold a lot of water, so the air starts to suck up what little water is around. At 30 to 50 degrees north and south of the equator, this falling air makes dry air drier. It also turns the land below it into a desert.

Listen to Joellen Russell discuss Hadley Cells in the audio download here.

Rainshadows

Oftentimes you will find a desert on one side of a mountain range, but not the other. Why might that be? If we think again about the rising and falling air that helps make deserts, it might make a little more sense.

Imagine warm clouds full of water vapor always moving toward a tall mountain range from the same direction. As the clouds cross the mountain range, the clouds are forced to rise up over the crest. This cools the air and the water being carried as vapor, or water-air, is squeezed out as liquid water. This action forces most of the water vapor out as rainfall, and this rain falls on that side of the mountain the clouds moved toward, called the windward side. This side of the mountains gets lots of rain.

But then, after the clouds have crossed the mountains and have dumped most of their water, they move down on the far side of the mountains, called the lee side. Wind continues to drive the now cool, dry air, but as that air moves down the lee slope of the mountains, it becomes warmer. This means that the air can again hold lots of water, so it again starts picking up water. This pulls water out of the soil and creates extra dry areas of desert on the lee side of the mountain range—what we call a dry shadow.

Water Blankets

You may have heard of water beds, but what about water blankets? Not a blanket made of liquid water, but one made of water vapor. Water vapor is essentially water-air, like the vapor that comes off of a boiling pot of water. Because deserts are so dry, they have very low humidity—the measure of water vapor in the air. So what does water vapor do for a biome?

A lot of water vapor in the air makes the air act as a water blanket, keeping in the heat or the cold better than air with low water vapor. Because deserts have such little water vapor in the air, it makes it harder to trap heat or cold in a desert.

At night, the sun no longer heats the desert and the heat from the day doesn’t stay trapped. Because of this, some deserts can get cold at night, dropping to below 40F, which is definitely coat weather.

In the daytime, the cold air from overnight doesn’t stay trapped. Because of this, when the sun rises, it can get very hot very quickly. Sometimes it can reach over 120F in the desert the very next day.

Additional images by Tomas Castelazo and Tahoenathan.

Karla Moeller earned her PhD in Biology at Arizona State University, studying how animals survive in extreme environments like the desert. She is an animal physiologist, a science writer, and a children's book author.

Read more about: Delving into Deserts

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Delving into Deserts

- Author(s): Karla Moeller

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/desert

APA Style

Karla Moeller. (). Delving into Deserts. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/desert

Chicago Manual of Style

Karla Moeller. "Delving into Deserts". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/desert

Karla Moeller. "Delving into Deserts". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/desert

MLA 2017 Style

![]() Try our Virtual Biomes

Try our Virtual Biomes

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.