Illustrated by: Sabine Deviche

Have you ever wondered how animals and plants get their names? People give them names, lots of different names! Even the simple cockroaches you see either inside of buildings or outside in their usual damp dark protected places have more than one name.

Even though roaches aren’t popular, their fossils show us that these successful insects have been on Earth for more than 300 million years. There are about 3,500 different kinds of roaches living today. One of these cockroaches, the Oriental cockroach, is found throughout the world and has a whole bunch of names.

Some of its many names are “waterbug” or a “black beetle,” but it isn’t either a bug or a beetle. Some animals and plants may have as many as six or more common names, and some of these are misleading. If you want to know whether you and another person are talking about the same insect, you need to use the scientific name, Blatta orientalis. When you write the name, you use italic letters to show that you’re using the scientific name. “Blatta” is a Latin word meaning “cockroach”, and “orientalis”, also Latin, means “east.” Many scientific names use Latin words, but some use Greek words. The word “cockroach” comes from the Spanish word, “cucaracha.”

How Did These Naming Rules Get Started?

We can thank a Swedish scientist for the system of naming plants and animals. Born May 23, 1707, Carl Linnaeus' name also has an interesting history. His father, Nils Ingemarsson, gave his family its permanent last name, in Latin, to honor a very large linden tree that grew on their property. Before the 1700’s, people in Sweden used names that said who their father was, for example: Carl Nil’s son or Olaf Sven’s son. Some of those names come to us today as Nilson, Nelson, Svenson, and Anderson. In the 1700’s, many Europeans decided to give themselves last names that they chose from Latin words.

Linnaeus was interested in plants and the naming of plants from the time he was a young boy. During his early years, his father taught him at home, and Linnaeus learned the names of many plants. Later he attended a grammar school until age 15 and then moved on to high school. He studied subjects that would have prepared him to be a priest, but he was not very interested in them, and one of his teachers suggested that Linnaeus would do better studying medicine.

Linnaeus left the school and studied with a doctor who was also a botanist studying plants. He entered Lund University as a student of medicine and botany when he was 21 and transferred to Uppsala University the following year. Along the way, Linnaeus had a number of mentors: people who took an interest in him and tutored him in different areas of medicine and botany.

During his career, Linnaeus took advantage of opportunities to explore the wildlife of Sweden. He was especially interested in plants useful to medicine. He also studied for several years in Holland where he earned his doctorate. Before returning to Sweden to become a professor at Uppsala, he visited both England and France.

As he studied plants and how they were named, Linnaeus became unhappy with how other scientists had grouped or classified them. He created a new system based on the parts of flowers, the reproductive structures of plants. He also used a new naming system that gave two names to each plant. Later this system of naming was extended to animals, as well.

In Linnaeus’s classification system, the two-part name of each plant was like a person’s last name followed by the first name, as you would find names in alphabetical order in a phone book:

Smith, John

Smith, Mary

Blatta, orientalis

Smith is like Blatta for our cockroach, and the first names in the list are orientalis. Linnaeus called the first name “Genus” and the second name “species.” Genus tells you that it is a cockroach and species tells you what kind of cockroach. The species name is usually a descriptive word. All the species of Blatta will have common characteristics, but there will be differences among the species.

It turns out that Linnaeus also named “Blatta orientalis”, so the name can be followed by “L.” or “Linné."

Blattaorientalis L

Blattaorientalis Linné

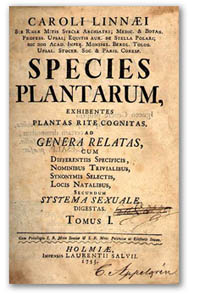

Linnaeus published a number of books during his life. His Species Plantarum was published in 1752 when he was 45. Six years later he published Systema Naturae which included 4,400 species of animals as well as 7,700 species of plants.

In 1761, the King of Sweden honored Linnaeus by making him a nobleman. From that time on, he was also known as Carl von Linné. When Linnaeus died in 1778, he was famous throughout Europe. Because he began the orderly classification of plants and animals, he is known as the father of modern taxonomy, the grouping of living organisms.

Additional images and illustrations from Wikimedia.

Read more about: Linnaeus and the World of Taxonomy

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Linnaeus and the World of Taxonomy

- Author(s): Ruth Kearns

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/linnaeus-and-world-taxonomy

APA Style

Ruth Kearns. (). Linnaeus and the World of Taxonomy. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/linnaeus-and-world-taxonomy

Chicago Manual of Style

Ruth Kearns. "Linnaeus and the World of Taxonomy". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/linnaeus-and-world-taxonomy

Ruth Kearns. "Linnaeus and the World of Taxonomy". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/linnaeus-and-world-taxonomy

MLA 2017 Style

What does taxonomy teach us about humans and how we fit into the tree of life? Learn more at Ask An Anthropologist's story Who Are You?

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.