Our history with fire

When you find humans, you find fire. Fire is so common in our lives that we often forget that it’s everywhere. It is part of almost every bit of modern technology. Glass, metal objects, bricks, and ceramics are made by using fire. Trains, planes, ships, and automobiles often burn fuel to carry us through the world. In 2019, fires in coal and natural gas plants created more than half of the electricity in the United States. Cooking food, lighting the darkness, heating homes: fire, fire, fire! But how long has this fire-mania been going on?

When did we first discover fire?

Every human culture on earth makes and uses fire. It has been our companion for a long, long time. In fact, humans have been using fire since before we were… well, human. Modern humans are the species Homo sapiens, but our ancestors called Homo erectus were cooking with fires before we even existed. Our very ancient ancestors were probably using fire as a tool almost one million years ago. Some anthropologists think it might have happened as far back as two million years ago.

We have been using fire for a very long time. This ancient hunting spear (Schöningen spear) is around 300,000 years old. Fire was used to harden the wood and make the weapon stronger. Scientists believe that it was made by an extinct Homo species that was an ancestor to modern humans. Image by P. Pfarr NLD via Wikimedia Commons.

Humans have always been using fire, even since the very beginning. Some biologists argue that fire is even what made us humans. Humans evolved large brains compared to our relatives like chimpanzees. But brains use up a lot of energy. Scientists think that our ancestors might have used cooking fires to keep those big brains running. When you cook food, you often make it easier to eat and digest.

Human-made forest fires

However, humans didn’t just keep their flames contained to little cooking fires. We have been setting entire landscapes ablaze for many years as well. Humans used burns to change the countryside around them.

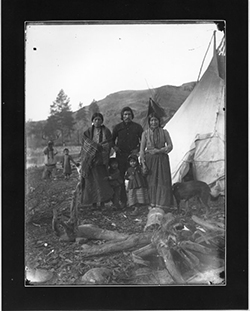

For example, the Methow people—a Native American group, whose homeland was taken and included as part of Washington State in the U.S.A.—would carefully start fires to make their homeland more like a giant garden. Tasty, quick-growing plants like edible ferns, camas bulbs, and many types of berries do better in areas that are often burned. The ash from the flames would help fertilize the plants too. Fires also removed unwanted grasses and made gathering acorns and hazelnuts easier.

The Methow would even burn parts of the forest to help hunt. Fires would guide deer into places where the Methow could easily catch them. Smoke would help them collect tasty grasshoppers to eat.

But the Methow people were not unusual. Aboriginal peoples in Australia would burn old grassland so that new grass would grow quickly and attract the kangaroos they hunted. Many cultures from all over the world would, and often still do, use different types of fires to manage landscapes. Think about how you control plants in your own yard or community. You might weed a garden, prune branches on a fruit tree, or mow grass. In the past, humans would use fire to do these sorts of things, but on a much larger scale.

Controlling fire, controlling people

All over the world, many groups of people continue their traditions of peacefully working with fire. Controlling fire is one important way of controlling the environment. However, in the past when outsiders invaded, they wanted to take control of the land for themselves. This often meant they would try to stop the native people from using fire to manage the land. They would sometimes ignore the knowledge of the native people. In the last several hundred years, these invaders were mostly Europeans who thought that they knew better than the people whose land they took. But each ecosystem needs a different amount of fire.

For example, for thousands of years the Karuk tribe used fire to manage their homeland before it was taken and included as part of California. Yet in 1850, the first year California became a state, European-American colonizers made it illegal to light these prairie fires. They wanted to control native peoples like the Karuk and to use the land for their own benefit. By controlling who uses fire, you can control the whole landscape.

But even in Europe, there was conflict over who could control fire. Peasants and farmers would often try to burn their fields before and after the harvest. This would add nutrients back to the soil. They wanted to use fires to clear weeds and open up new areas to farm. However, their rulers and the wealthy landowners saw large fires as threatening and dangerous to their own interests, so they would try to prevent any fires from starting.

Forestry and fires in the United States

Continental Europe was where “modern” forestry first began. Foresters are people whose job is taking care of large forests and woodlands. In the late 1800s, forestry started using science to help manage land, but this science was based on woods from Europe. These temperate forests are some of the few areas where natural wildfires rarely happen.

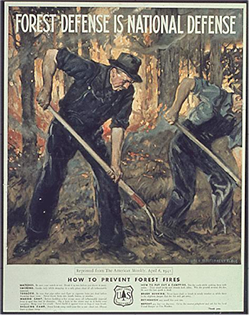

The first foresters in the United States were also trained in Central Europe, and they brought European anti-fire ideas with them. In Europe, fire was used by common people for farming and raising livestock but was hated by elites. Because foresters worked for these rich elites, the foresters did not like fires either. The foresters carried these ideas to the United States, but not all of them agreed on this.

The US Forest Service wanted every citizen to help prevent forest fires. This 1941 poster compares stopping forest fires to defending the country from the threat of World War II. Image by USFS.

When foresters began working in the western United States, some of them listened to the knowledge gained by Native American tribes like the Karuk. They called prescribed burns “the Indian Method” of preventing wildfires. However, many of the white foresters thought that this idea was incredibly foolish. Because of their previous training, and many having racist views, they refused to believe that Native Americans knew how to conserve the forests.

Trying to stop fires before they start

After a series of gigantic wildfires in 1910, the United States tried to stop any and all wildfires. The U.S. Forest Service wanted to keep forests from burning so that they could protect wood for timber and to keep ash from getting into rivers and lakes. Fires were seen as evil, and early U.S. forester Bernhard Fernow said they were caused by “bad habits and loose morals.” For more than the next 50 years, much of the Forest Service’s time and money were spent preventing fires and putting them out as quickly as they could. Little did they know, the obsession with fire suppression could actually hurt many forests.

Without fires, dead wood began to build up in the forests. There were no fires to remove this extra fuel. Then, when a fire finally would start, the extra fuel would make the wildfire become much hotter, larger, and more dangerous. The Forest Service spent more and more money trying to keep things under control, but it seemed like each year would be worse than the previous one. They now spend over half of their annual budget just on fire-fighting.

It was only in the 1960s when things began to change. Experience showed that certain fires could be helpful, a fact that native peoples like the Methow and Karuk had already known for centuries. The foresters would sometimes let these natural fires burn when they weren’t close to cities or towns. They would also start their own carefully controlled fires, to make sure certain areas didn’t gain too much dead wood, dry shrubs, or pine needles. Slowly, the Forest Service and other government groups in charge of the land began to change their plans. Now there are regular controlled burns in some areas, although many scientists think this is still not enough.

Fires of the future

This change in policy may be an example of “too little, too late.” After almost 100 years of trying to prevent almost all fires, wildlands are different than what they used to be. Without enough of the right kind of fires, many areas have changed. Some forests are packed with burnable fuel. These new types of ecosystems are likely to have new, more dangerous types of fires.

Such forests are similar to a ticking time bomb: at some point they are going to burn. And when they burn, it will be bad. It may be scary, difficult, and expensive at first, but it is likely that the U.S. will need to start many, many of their own fires before things are under control.

Does climate change affect fires?

Unfortunately, climate change is only making this problem worse. Hotter temperatures, less rain, and unpredictable weather will increase the chance of deadly fires. It is clear that the only way forward is through fire. The good news is that humans have been working with fire since before the beginning. We need to accept that flames have an important role in our world, we need to continue to study burning forests, and we need to put the right fire in the right places.

Image with dead and fallen trees by the National Park Service.

Read more about: Are Wildfires Bad?

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Our History with Fire

- Author(s): Dr. Biology

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/human-fire-history

APA Style

Dr. Biology. (). Our History with Fire. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/human-fire-history

Chicago Manual of Style

Dr. Biology. "Our History with Fire". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/human-fire-history

Dr. Biology. "Our History with Fire". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/human-fire-history

MLA 2017 Style

Without the occasional light burning to remove dry plant material, dead and fallen trees can begin to pile up. With so many logs on the ground, sometimes a forest can seem like one giant campfire waiting to be lit. Imagine how difficult it would be to stop such a large fire.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.