Illustrated by: Sabine Deviche

You look into the crackling flames of the campfire. The orange lights dance, spread, and change, as if they have a mind of their own.

Is fire alive?

Steven Pyne, a fire expert, compares wildfires to viruses. Just like viruses, fire is connected to life, but not alive. Both need the living world to spread and exist and both can be dangerous. Image by Marcus Obal via Wikimedia Commons.

To you, this fire almost looks like it’s alive. The same could be said for wildfires. They can grow larger, spread, and die down, as if they were living organisms, rather than just chemical reactions. However, fires are most certainly not alive, even if they do need living beings to exist. But what is fire then? How can it move? What is it made of?

What is fire?

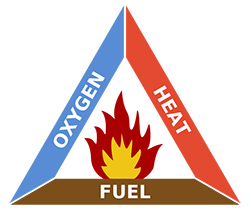

On the deepest level, fire is a chemical reaction that turns fuel and oxygen into water vapor and other gases. Fires need three main things exist: fuel, oxygen from the air, and heat. Together these parts are called “the fire triangle,” because if you take any one of them away, the fire will die out. Fires also need a spark, heat, or a small flame to begin.

When something hot enough touches a fuel source like a tree, dry grass, or a pile of leaves, a fire can suddenly start. Things become hot and microscopic bits of oxygen and the fuel source rip apart and then combine in incredibly tiny mini-explosions. However, this reaction doesn’t make the yellow and orange flames that you can see.

Those flickering tongues of orange light are made up of tiny molecules of hot soot released by the fuel. The microscopic bits of carbon and ash are so hot that they turn into gas while glowing and giving off light before being burned up. Think about glowing lava or white-hot metal, it is the same type of effect. Hot air rises (this is how hot air balloons float), so the heat from the fire carries these glowing soot pieces into the air, making those flickering tongues of flame.

Although fires are created from life, they also help create more life. The wood and grasses that fuel fires are made from living things. When fires burn this material, the flames can release the nutrients stored in dead plants. The ash from these fires can be good for new plants to grow. Fire is part of the life cycle.

You can also think of fire as the opposite of photosynthesis. Plants use energy from the sun to grow and make tissues, and this process is called photosynthesis. During photosynthesis, plants also release oxygen. But fires destroy this plant material and release all the energy back into the air as heat and flame. They even use up oxygen from the air as they burn.

Fire makes everything around it hot, so when a tiny spark, a small ember, or a bit of flame blows away from the fire and touches some nearby fuel…you have trouble. There’s fuel, heat, and air: everything a fire needs to start and to spread. Fire has been helping humans for hundreds of thousands of years. We use it to cook food, warm our houses, and create electricity. But if we aren’t careful, fires can become deadly too.

The dangers of wildfires

Gray smoke hides the sun and darkens the sky, even in the middle of the day. Orange flames glow in the distance, destroying homes and making the landscape look like a nightmare. Teams of firefighters are trying their best to control the disaster, but it seems like all the trees are burning for miles and miles. There is no doubt about it, wildfires are incredibly scary.

Wildfires can destroy buildings and homes, burn up forests, and even take lives if they aren’t controlled. Many families and communities have had to leave their homes when fires are nearby. Each year, wildfires cause more than $5 billion US dollars in damage, and this number is only increasing. Some scientists estimate that the total cost of California’s 2018 wildfires was anywhere from $150 billion to $400 billion dollars.

Even if you don’t live in an area with wildfires, they can still hurt you. Gigantic wildfires shoot huge amounts of smoke and soot into the air. The smoke from wildfires can make breathing air dangerous for hundreds of miles.

If these fires are very big, they are more likely to hurt animal life. Many biologists worried that Australia’s wildfires in 2020 could even cause some endangered animals to go extinct. It seems that many of them managed to survive through the fire, but now that their habitats are destroyed, they may still be in trouble.

The benefits of forest fires

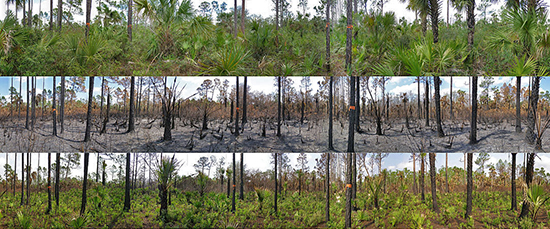

Although wildfires in the news are often harmful, most wildfires are good. Many fires actually help the environment. Natural fires were part of the world well before humans evolved. Lightning strikes start wildfires when they hit old, dead trees or dried grass.

But when these natural fires burn through an area, they make room for new plants to grow. In fact, some plants have come to rely on these fires to live; we call these pyrophytes. For example, lodgepole pines in the USA and banksia trees in Australia make seed cones that will open in the heat of a fire. This way, the seeds are guaranteed to start germination right after a fire, when there is less competition for sunlight. In many places, burning is part of a natural, healthy life cycle.

It seems odd, but small fires can prevent big ones. Smaller, less dangerous fires can burn through and remove the dry, dead logs and plants that build up over short periods of time. These tiny fires are often not hot enough to hurt established living trees. But without the occasional fire, forests can slowly fill up with dead logs covering the ground. Then when a fire starts (and in most places a fire will eventually start), there is so much fuel that the wildfire burns incredibly hot and can get out of control. These huge fires are extra dangerous and can kill even the strongest living trees.

This is why understanding fire is so important. Fire itself is neither good nor bad. The important thing is for us to try to prevent bad fires and promote good fires. If we develop the right strategies using our knowledge of wildfires, we can turn it into an ally instead of an enemy.

The right fires for the right places

All over the world, plants and animals have figured out how to live in harmony with the wildfires that naturally happen where they live. But there are many different types of wildfires across the globe: some are larger and some are smaller. Some spread quickly and lightly, others are slow and intense. Some burn the whole landscape and some wildfires just burn in small patches without spreading everywhere.

On top of this, the amount of time between wildfires can be very different too: in some places fires burn every year, while in others fires will only show up every 120 years! These different patterns of wildfires and burning are called “fire regimes.” Each place on earth has its own special fire regime, and the animals and plants that live there are used to it.

You can think of fire regimes like patterns of rainfall: different places need different amounts of rain. If you could somehow switch the amount of rain between a desert and a rainforest, it would be a catastrophe for both places! If there is less rain than normal, plants will dry up and animals will go thirsty. If there much more rain than normal, floods could sweep everything away. It is all about matching the right pattern to the right place. This is why it is so important to study wildfires and learn which kinds are suited for each environment.

Image of the sun in a smoky sky by Karla Moeller.

Read more about: Are Wildfires Bad?

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Are Wildfires Bad?

- Author(s): Andrew Burchill

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/wildfires

APA Style

Andrew Burchill. (). Are Wildfires Bad?. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/wildfires

Chicago Manual of Style

Andrew Burchill. "Are Wildfires Bad?". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/wildfires

Andrew Burchill. "Are Wildfires Bad?". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/wildfires

MLA 2017 Style

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.