World's Deadliest Scorpion

The deathstalker scorpion is one of the deadliest scorpions in the world. Its tail is full of powerful venom. A deathstalker scorpion's sting is extremely painful and also causes paralysis, an inability to move or feel part of the body. The scorpion uses this venom to hunt insects such as crickets, which are its main food source.

The deathstalker scorpion catches its food by taking its prey by surprise. It hides under rocks in wait for an unsuspecting cricket or other small insect, then springs out and grabs it. Because its pincers aren't very strong, it needs to sting its prey quickly to keep it from getting away. Within moments of being stung, the cricket is paralyzed or dead, giving the scorpion plenty of time to enjoy its meal.

Let's take a closer look at muscles and how venom effects the cells in your body.

How Do Muscles Work?

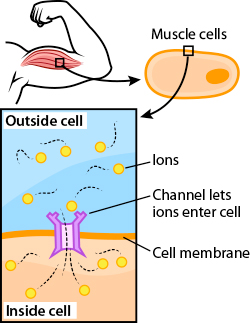

The muscles in your body are controlled by the movement of special molecules called ions. Depending on the type of ion and whether its moving in or out of muscle cells, the cells either relax or contract. One such ion is chloride, which helps muscle cells know when to relax. When all the cells in a muscle are contracted, that muscle is flexed. This makes it possible for you to move your arms, legs and other parts of your body.

Ions enter muscle cells through openings in the cell membrane called channels. These channels are made of proteins and have a specific shape that let only certain molecules or atoms pass. Chloride channels, for example, are specifically designed to only let chloride ions in and out of the cell.

How Does Venom Work?

Now that you understand how muscles work, let's take a closer look what venom does inside your cells.

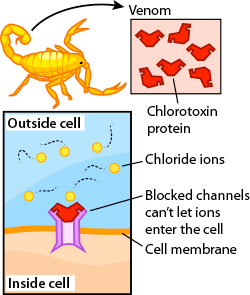

Scorpion venom contains a very small protein chain called chlorotoxin, only 36 amino acids long. This tiny protein has a very powerful effect though. It is perfectly shaped to block chloride channels and stop chloride ions from entering muscle cells. Without these ions sending signals telling your cells to relax, the muscles in your body all flex at once and paralysis sets in.

Shape Matters

The shape of a protein is very important. This is what makes it possible for a protein to interact with other proteins and parts of the cell. It’s like having two pieces of a puzzle that fit together, or like having the right key for a certain lock. If a protein is not folded correctly, it doesn't have the right shape and doesn't fit with parts of the cells.

Scorpion chlorotoxin, for example can be folded in at least 256 different ways. Yet only one of these works correctly to block chloride channels in your muscle cells.

Venom in Medicine

In nature, animals use venom for self-defense or to catch prey. In the lab, scientists are finding out that venomous proteins can be used in medicine.

Researchers have had success, for example, in using scorpion venom to treat brain tumors in humans. Instead of causing harm to healthy nerve and muscle cells, venom such as chlorotoxin can be used to block signals from cancer cells. Blocking these signals prevents them from growing.

Scientists have also discovered ways in which the effect of paralysis can be helpful for humans. When a patient goes into surgery, for example, it's important for their body to stay very still while the doctor performs the operation. Even a tiny movement could cause a very big mistake! So, in addition to drugs that cause sleep, patients are often given drugs that cause temporary paralysis while the doctor performs the surgery.

The more we learn about proteins and their shapes, the more we understand about what might go wrong in our bodies and why. Knowing this helps researchers design better medicines and treatments.

Read more about: Venom!

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Scorpion Venom

- Author(s): Dr. Biology

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/venom/scorpion_venom

APA Style

Dr. Biology. (). Scorpion Venom. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/venom/scorpion_venom

Chicago Manual of Style

Dr. Biology. "Scorpion Venom". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/venom/scorpion_venom

Dr. Biology. "Scorpion Venom". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/venom/scorpion_venom

MLA 2017 Style

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.