Life as a Tardigrade

Every animal starts life off little. This is especially true for tiny tardigrades! They have three life stages – egg, juvenile, and adult.

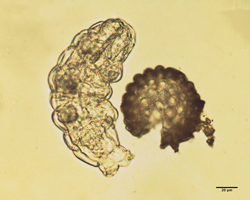

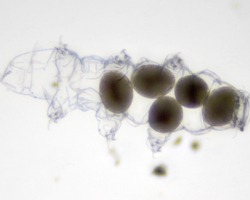

Tardigrade eggs are round and can be covered in strange and spikey shapes. When the egg hatches, out comes a small tardigrade. This part of their life is called the juvenile stage. Juvenile tardigrades work hard to eat and grow to an adult size. To grow larger, tardigrades molt. That means they grow a new and bigger skin, then shed their old one. Depending on the species, tardigrades will molt four to twelve times. When they molt as adults, tardigrades will often lay their eggs inside their old molt to help protect them.

In a comfortable and wet habitat, a tardigrade can live between three months and two and a half years. Tardigrades that go into protective sleep, or get frozen in ice, can live as long as ten to thirty years.

Dealing with the Seasons

Through the year, as seasons change, the water that tardigrades live in can become uncomfortably warm or cold. Sometimes, changes in temperature mean there isn’t enough air in the water for the tardigrade to breathe. To prepare for these changes, some kinds of tardigrades make a tough outer shell called a cyst (pronounced like “sist”). In the cyst, they rest and save energy until things get better.

The tardigrade makes a cyst by shedding its skin two or three times without swimming out of it. The skins build up, one inside the other, like layers of an onion. As the old skin toughens around it, the tardigrade curls up and goes to sleep. It stops moving and uses less energy, and slowly uses the food and fat stored in its body. When the temperature is nice again, it cracks through the cyst and leaves it behind.

A cyst is not as extreme as other tardigrade survival tricks. But, it’s an important part of the yearly life cycle for certain species.

Making More Tardigrades

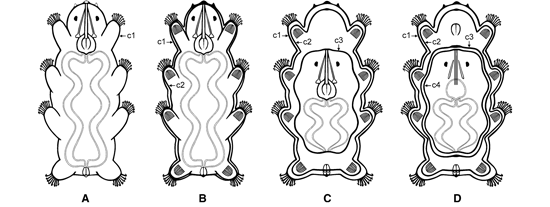

Male and female tardigrades are hard to tell apart, unless the female is full of eggs. A female tardigrade has such big eggs that they take up almost her whole body. Males make sperm, but the body parts where this happens are hard to see unless you know what you’re looking for.

Some tardigrades are both male and female, and can make both sperm and eggs. These are called hermaphrodites. Other kinds of tardigrades are parthenogenic. This means the tardigrades are born from a female’s unfertilized eggs. Her children are nearly her clones, and there are no males in the population.

Additional images via Flickr. Image of colobus monkey mom and baby by Eric Kilby via Wikimedia Commons.

Read more about: Itty Bitty Beasts

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Life as a Tardigrade

- Author(s): Dr. Biology

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/tardigrade-life

APA Style

Dr. Biology. (). Life as a Tardigrade. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/tardigrade-life

Chicago Manual of Style

Dr. Biology. "Life as a Tardigrade". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/tardigrade-life

Dr. Biology. "Life as a Tardigrade". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/tardigrade-life

MLA 2017 Style

Many young animals look like mini versions of their parents, like in these colobus monkeys. The same is true for tardigrades.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.