Illustrated by: Megan Joyce

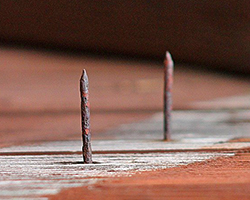

Your game of hide and seek has gotten serious. You’re in the back corner of a friend’s barn, worrying what spider webs you might be leaning into. As you look up in the corners around your head, you take a step back and a searing pain shoots through your toe. You’ve stepped on a rusty nail.

You’ve been warned about rusty objects. As you take your shoe off and put pressure on the wound, you realize a nasty kind of bacteria, Clostridium tetani, may have entered your system. If left alone, within a few days, that bacteria may grow into an invading force that causes tetanus, an infection that affects your nervous system.

Tetanus can cause muscle spasms, make your jaw lock up, and it might make breathing difficult. But you remember—your dad made you get another tetanus shot a few years ago. Thanks to that vaccine, your body is already trained to fight this invader, so your only worry is keeping the wound clean, and you call out for your friend to help you get home.

What is a vaccine?

A vaccine is a treatment that trains the immune system to fight off specific microbes. Instead of having to get sick from the dangerous microbe, a vaccine trains your body to fight it using dead or weakened microbes (or pieces of those microbes). In this way, vaccines teach your immune system what specific germs look like, so your body can practice fighting those germs. If those germs try to invade again, your body already knows what defense to prepare. It will fight off the germs more quickly and successfully, so you can stay protected.

A brief history of vaccines

Have you ever wondered why a vaccine is called a vaccine? One hint is the root of the word vaccine, vacca, which is Latin for cow. Why are vaccines named after cows? Well, let’s take a look at how vaccines were discovered.

In 1768, a young apprentice was working with a country surgeon in England. The young man, named Edward Jenner, was helping his supervisor try to prevent bad cases of smallpox in the local communities.

Back then, smallpox felt like a curse on humanity. Many people were dying in Europe and around the world because of smallpox. Humanity needed a cure to this terrible disease. At the time, they were using inoculation to try to prevent death from the disease. People would be exposed to the material in a pustule through small cuts in the skin. This method would give the patient the disease, but a less severe case of it, and it would protect them from more severe cases.

It was during this time that Jenner first learned of cowpox, which is a sort of cow version of smallpox that could still infect people. The infections and stories of cowpox versus smallpox were a bit of a tangled mess, but it seemed like those who had had cowpox didn't have as much of a reaction to smallpox inoculation. After another year of apprenticing with a different surgeon, Jenner returned home and became a country doctor.

After many years of treating patients, in 1796, he was asked to inoculate a young boy against cowpox, to avoid an outbreak that was happening locally. He did so, and then a few months later, tried inoculating the boy against smallpox. Though cowpox and smallpox were known to be related, it wasn't until this experiment that anyone had tested the idea that cowpox inoculation might directly protect against smallpox.

Jenner made this discovery, as the boy had a reduced response to smallpox inoculation. From then on, treatment with cowpox (called vaccination) to reduce risk of smallpox started to spread and help protect the public against smallpox. This discovery saved countless lives and paved the way for the discovery of other vaccines.

Today vaccines are made in many different ways, but it always comes down to the same result: creating immunity to a germ in a similar way as was done with Jenner’s cowpox vaccine. And that is why vaccines were named after the cow, because cowpox was used for the first vaccine, against smallpox.

Protection in the herd

A small herd of wildebeest grazes in a field in the African savanna. In the middle of the herd, a calf walks next to its mother. The calf doesn’t know it yet, but it has caught the attention of a pack of African wild dogs. Some of the wildebeest notice the wild dogs, and they stomp their hooves and make warning calls. But the herd is scared and starts to run. Soon, the calf is running for its life.

The calf is small and tries desperately to keep up with the herd because it knows there is protection there. The dogs’ eyes are focused on the little calf, an easy target, but they cannot reach it. The calf’s mom and the other antelope are still surrounding the calf to protect it. The herd manages to get away without injury and make it to their new pasture. If it hadn’t been for the protection of the herd, the calf would have been an easy meal for the wild dogs.

What is herd immunity?

You might be wondering what wildebeest and wild dogs have to do with vaccines. Well, the story of that little calf helps to describe a term called “herd immunity” that people often use when talking about the importance of vaccination. So, what is herd immunity?

Vaccinated people can help protect those who can't be vaccinated for medical reasons. This "herd immunity" is similar to the protection of keeping a young wildebeest on the inside of a herd, separated from the attacker. Image by shankar s. via Wikimedia Commons.

Herd immunity is a concept about how vaccinated people can help protect unvaccinated people from getting sick from a disease. Wild dogs and wildebeest can show us how herd immunity works, except it is germs that we are trying to protect against. The adults in the herd can be thought of as all those who are vaccinated against a germ. The vaccinated can help protect the unvaccinated from becoming infected, as the adults in the herd protected the calf from being eaten.

When a population is not vaccinated against a certain microbe, the microbe can spread very quickly from person to person. But when most of the population is vaccinated against the germs, that process is much harder. When the microbes enter a vaccinated person, that person’s body can kill the germ before it spreads to infect other people. That way, even if there are a few people who are not vaccinated and are at risk of getting sick, the other vaccinated people help protect them.

In the story, the adult wildebeest in the herd kept the calf safe. But what do you think would have happened if there had been more calves or fewer adults in the herd? Would there be enough protection for the calves?

Who shouldn’t be vaccinated?

Vaccines are a type of preventive medicine. And like with any medicine, some people (very few) may be allergic. Those who are actually allergic to a vaccine definitely should not get vaccinated. Others with immune problems and those that are too young also should not be vaccinated against certain germs. But we, as a society, can protect these people from getting infected by being vaccinated ourselves.

By getting vaccinated, we create a shield against infection so those who cannot be vaccinated are still protected. If everyone who can get vaccinated does so, it keeps the shield strong. But if people who can get vaccinated decide not to, it creates more gaps in the shield, and more risk that the infection may sneak through.

If enough people are vaccinated against a specific disease, we may be able to wipe out that disease all together. Smallpox is a great example. For the most part, we no longer need to be vaccinated against smallpox because it was wiped out through widespread vaccination. However, unless a disease is eradicated, we must support herd immunity by getting our vaccines.

Vaccines protect from infection

Thanks to vaccines, we have a way to protect ourselves from diseases such as tetanus, chicken pox, hepatitis, polio, measles, and many, many more. And, by getting vaccinated, we can help protect those around us through herd immunity. Vaccinations are an important way to protect your health and the health of those around you. If you have any concerns about whether you are in a vulnerable group that shouldn't be vaccinated, make sure to consult a medical doctor.

The origins of vaccination: Myths and reality https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3758677/

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Vaccine science

- Author(s): Ian Vicino, Mary D. Pardhe, Karla Moeller

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/vaccines

APA Style

Ian Vicino, Mary D. Pardhe, Karla Moeller. (). Vaccine science. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/vaccines

Chicago Manual of Style

Ian Vicino, Mary D. Pardhe, Karla Moeller. "Vaccine science". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/vaccines

Ian Vicino, Mary D. Pardhe, Karla Moeller. "Vaccine science". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/vaccines

MLA 2017 Style

An illustration by David S. Goodsell showing vaccine molecules in pink that are similar to a virus the vaccine protects against. The vaccine molecules attach to the outside of an immune cell. In response, the immune cell will create antibodies that can fight the actual virus.

Try our COVID simulator to experiment with how different safety measures can affect the spread of the virus that causes COVID-19.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.