If you’ve ever done a word search puzzle, you know it can be hard to find short sequences of letters among lots of other letters. An average word search has maybe 400 letters, and has a lot of variation, with all the letters of the alphabet. But searching the genome for a specific sequence is much, much harder.

Searching the human genome, you are looking for short sequences using combinations of only four letters (A, C, G, and T). These stand for the four nucleotide bases for DNA (adenine, cytosine, guanine, and thymine). And you’re looking for a specific sequence—let’s say ACTGTATGT—in a puzzle that is three billion letters long. It’s a puzzle 750,000 times as large as a usual word search, with letters in two long rows. So, how does CRISPR work to find and change something so specific in such a large puzzle?

Anatomy of CRISPR

Let’s review some basics very quickly before getting into that. There are many different varieties of CRISPR tools used in gene editing. But the most common is called CRISPR Cas9. CRISPR Cas 9 is named for the specific CRISPR-associated (Cas) enzyme that cuts the DNA. Other CRISPR tools use other Cas enzymes, like Cas3 or Cas10. But for now, we will focus on Cas9 as our example.

The CRISPR Cas9 gene editing tool has two main parts, one larger and one smaller. The larger part is the Cas9 enzyme, which cuts the DNA at a particular site. The smaller part is a short sequence of nucleic acids called guide RNA (gRNA). gRNA helps the CRISPR system target its particular matching DNA site. These parts work in two steps: seek (find) and snip (cut).

Seek and Snip

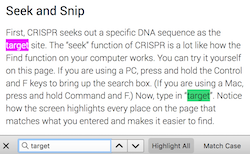

First, CRISPR seeks out a specific DNA sequence as the target site. The “seek” function of CRISPR is a lot like how the Find function on your computer works. You can try it yourself on this page. If you are using a PC, press and hold the Control and F keys to bring up the search box. (If you are using a Mac, press and hold Command and F.) Now, type in “target”. Notice how the screen highlights every place on the page that matches what you entered and makes it easier to find.

The gRNA is like the word you entered in the Find search box. It helps CRISPR find those places in the genome that match the gRNA. Scientists design the gRNA to be complementary to the base sequence of the DNA at the site they want to cut. The complementary sequence enables the CRISPR system to loosely bind to the DNA at the targeted location.

Once the gRNA has located the target site, the Cas9 enzyme snips the DNA at that site of the genome like a pair of scissors. Cas9 cuts across the DNA, breaking it in two. Together, the gRNA and Cas9 enzyme let scientists cut DNA at very precise locations in a cell’s genome.

Whenever there is a break in a cell’s DNA, the cell can sense that its DNA has been damaged. In response, the cell tries to repair the break in the DNA by joining the two pieces back together. Gene editing takes advantage of these natural repair processes to enable scientists to make their own intentional changes to a genome.

Out with the Old

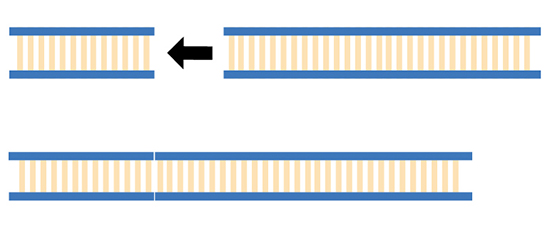

When a cell tries to repair broken DNA, the repair can happen in one of two ways. The first, more common way is called nonhomologous end joining (we’ll just call it end joining). In end joining, the cell tries to directly reattach the cut ends of the two pieces of DNA. Sometimes this is successful, and if no bases were added or removed, the repaired DNA is exactly like it was before the cut. But this process is not always perfect, and mistakes can happen during repair.

Sometimes new nucleotide bases are added where the cut was made or bases from the ends of the cut DNA are removed during the repair. The result is a DNA sequence that may be different where the cut was made. The difference in base sequence can result in the gene no longer functioning. End joining usually results in gene disfunction. This lets scientists study what genes do by comparing cell behavior before and after editing through end joining.

In with the New

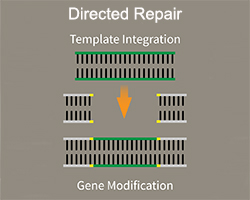

The second way that a cell can repair a break in its DNA is by homology directed repair (we’ll call this directed repair). Directed repair enables new bases or entire genes to be added to a genome. It can also be used to replace existing bases or genes. Directed repair accomplishes this by using a DNA donor template. Donor templates are typically short, linear sequences of DNA designed by scientists to tell the cell how to repair the cut site. Donor templates have three main sections.

In the middle of the DNA template is the sequence of bases or the gene to be edited into the genome. On either side of the sequence are much longer sequences called homology arms. Each of the arms exactly match the DNA sequences on either side of the original cut site.

Normally, when a cell tries to repair a break in its DNA, it looks at DNA sequences near the cut site to guide how to join the DNA back together. In directed repair, the donor template is very similar to the original sequence around the cut site, except for the new nucleotide sequence or gene to be added. So, when the cell looks for a guide to repair the DNA break, it uses the template instead of other DNA. As a result, the insert sequence from the template is copied into the cell’s repair of the DNA break.

Read more about: Cutting DNA with CRISPR

Bibliographic details:

- Article: How Does CRISPR Work?

- Author(s): Dr. Biology

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/how-does-crispr-work

APA Style

Dr. Biology. (). How Does CRISPR Work?. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/how-does-crispr-work

Chicago Manual of Style

Dr. Biology. "How Does CRISPR Work?". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/how-does-crispr-work

Dr. Biology. "How Does CRISPR Work?". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/how-does-crispr-work

MLA 2017 Style

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.