Messages in the Body

You fold up a small piece of paper. The teacher isn’t looking – now is your chance. You nudge your classmate to your right, place the paper on their desk, then point to your friend to their right. They pass it to your friend. Your friend opens the paper, and by the smile that glides across their face, you can tell that the message is received: meet after school for tacos.

But the piece of paper that your friend read was only one of thousands of messages that were just passed. Most of these messages happened in your body. In many ways, our bodies depend a lot on messages that it passes from one place to another. Imagine if your body did not communicate with itself – how would it know when you are hungry? Or what time of day it is?

Making Messages

The cells in our bodies communicate with each other. They do this by using chemical messengers, or special molecules. Hormones are an important type of messenger. Hormones are small molecules that are created in one cell, then sent out to other cells through the blood or other body fluids.

Certain hormones only affect certain cells that have the receptor for that hormone. These are called target cells. When hormones arrive to a target cell, they may bump into a hormone receptor. You can think of it like the hormone being a key, and the receptor being a lock. Or, like the hormone being the caller, and the receptor being someone who picks up the phone. After the hormone attaches to a hormone receptor, a chemical message is sent inside the cell. Then, work inside the cell can begin.

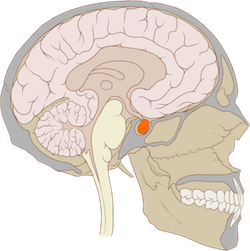

Hormones are sent to in the bloodstream, so can reach most cells in the body. For example, a hormone called growth hormone is made in the pituitary gland, a small gland at the base of the brain. It then enters the bloodstream, where it circulates all around the body, and can arrive at cells all the way from the bone cells on your head to the skin cells on your toes, and everywhere in between. But growth hormone will only affect cells that have the receptor for growth hormone.

Specific Signals, or Broad Effects

Animals have lots of different hormones. Each hormone has a specific job or set of jobs. Often their job is to get all of the cells ready for a certain function or stage of growth. Some hormones help animals grow (like growth hormone), control their metabolism (like thyroid hormone), or figure out what time of day it is (like melatonin). Some hormones have jobs all over the body, like thyroid hormone. Others mostly go to work in specific parts of the body.

To look at the difference between specific and broad-acting hormones, think about a time that you felt very scared or stressed – maybe you were on a rollercoaster. When you get that feeling, your body thinks that it should have a lot of sugar to be ready to respond to whatever happens.

Your brain starts making a hormone: corticotropin-releasing hormone. That hormone sends a specific signal, only to one specific part of the body (the pituitary gland), to start making another hormone. The hormone the pituitary gland releases, called adrenocorticotropic hormone, is also specific. That hormone is sent into the bloodstream, and moves past most of the cells in the body. It eventually reaches cells within small glands that sit on top of the kidneys, called adrenal glands. The cells in the adrenal glands have receptors for adrenocorticotropic hormone, so they get the message.

Then, the adrenal glands start pumping out a hormone called cortisol. Cortisol is a broad-acting hormone, meaning when the signal is sent, cells in many different tissues across your body get the message. Cortisol is thought of as a stress hormone. It tells your body to start releasing energy and puts your brain in survival mode.

One Hormone, Different Effects

The same hormone can do different things in different animals. In mammals (like us), the hormone prolactin causes females to produce milk. Birds also have lots of prolactin, but they don’t have the glands to make milk. So, why do birds have prolactin? Prolactin, it turns out, helps cause parental behaviors. When researchers give birds extra prolactin, they start caring for their offspring more, by protecting and feeding them better.

Fish are the ancestors of both mammals and birds, so they share most of the same hormones. But unlike in those groups, in fish, prolactin does not have a reproductive function. It does not help them care for their offspring better, and it does not help fish produce milk, because they lack mammary glands. Instead, it mostly goes to work in the gills, where it helps regulate the flow of ions or salts into and out of the body. As you can see, one hormone can mean something very different to a mammal, a bird, or a fish.

But, keep in mind, not all animals have the same hormones. Insects have several hormones that vertebrates do not have. Insects have juvenile hormone (which stimulates growth among other things) and ecdysis hormones (that help insects molt, or shed their exoskeletons). Vertebrates don’t make either of these hormones. Hormones evolved in animals long ago. But there are many different hormones, or many uses for the same hormone across the animal kingdom.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Asian common toad from Hong Kong, by Papa Lima Whiskey, with modifications made by Lokionly.

Read more about: Focusing on Physiology

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Hormone Systems

- Author(s): Dr. Biology

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published:

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/animal-endocrinology

APA Style

Dr. Biology. (). Hormone Systems. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/animal-endocrinology

Chicago Manual of Style

Dr. Biology. "Hormone Systems". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . https://askabiologist.asu.edu/animal-endocrinology

Dr. Biology. "Hormone Systems". ASU - Ask A Biologist. . ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/animal-endocrinology

MLA 2017 Style

Hormones control so much of our physiology. Some hormones are involved in controlling hydration state, an especially important function in amphibians, like this Asian common toad.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.