Investigating In Vitro Fertilization

Illustrated by: Sabine Deviche

show/hide words to know

Egg: a female gamete, which keeps all the parts of a cell after fusing with a sperm.

Embryo: the egg after fertilization and before it has developed into a recognizable form.

Hormone: a chemical message released by cells into the body that affects other cells in the body.

Infertility: an inability to become pregnant or contribute to causing pregnancy after 12 months of trying by having unprotected sex.

Ovary: creates and stores the female reproductive cells in plants and animals.

Sperm: a male gamete, which fuses with the egg during fertilization... more

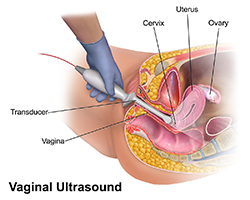

Ultrasound: a technique for making an image of what is inside the body......more

Uterus: or womb is a major female reproductive sex organ of most mammals including humans. It is within the uterus that the fetus develops... more

IVF is a common way for people with infertility to become pregnant. About four million women in the US use IVF every year to start a pregnancy. Image by George Jr Kamau via Pexels.

Sarah steps out of her car and looks at the crumpled pamphlet in her hand. She reads the title, “In Vitro Fertilization (IVF),” one last time.

Stuffing the pamphlet in her purse, Sarah marches up the stairs to the doctor’s office. She has decided to undergo IVF.

She and her partner have been trying for years to get pregnant, but so far, they’ve had no luck. The doctor told her she has trouble ovulating, or releasing an egg, which is needed for pregnancy to start. That makes Sarah infertile, though there are other causes of infertility, too.

Infertility is not rare. In fact, 11% of women of reproductive age in the US struggle with some form of infertility. So do 9% of men in the US.

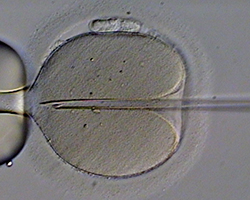

One other way to fertilize an egg outside of the body is by ICSI, or intracytoplasmic sperm injections. Instead of letting the sperm fertilize an egg on a petri dish like in IVF, sperm is injected directly into an egg. Image by Eugene Ermolovich (CRMI) via Wikimedia Commons

Female infertility isn't always due to problems releasing an egg. Other causes might be related to problems with the number and quality of eggs a female has, or problems with an embryo being able to implant in the uterus. Male infertility might be caused by factors like having a low sperm count. Other factors might have to do with the shape of sperm or sperm's ability to move through the female body. All of those factors can make it harder for the sperm and egg to fuse to cause a pregnancy.

Luckily, there are a few technologies that can help couples who want to get pregnant where either partner is struggling with infertility. One of them is IVF.

IVF is a procedure where a doctor makes sperm and egg come together outside the human body. Once the egg is fertilized, the doctor transfers the resulting embryo back into the patient’s uterus.

If all goes well, the embryo will attach to the uterus, resulting in a normal pregnancy. Upon delivery, the patient can give birth to a healthy newborn.

Let’s follow Sarah’s journey undergoing IVF.

Prepping for the Procedure

The first step of IVF is collecting some of Sarah’s eggs. To make that easier, Sarah’s doctor gives her hormone injections. The injection will make Sarah hyper-ovulate, or release more than one egg at once.

A person wanting to go through IVF may get hormone injections, medications, or both. A common drug that a doctor may give a person going through IVF is called clomiphene citrate. That drug helps promote ovulation. Image by olia danilevich via Pexel.

Making a patient hyper-ovulate allows doctors to maximize the number of eggs they collect at a time. Hopefully, that means Sarah won't have to repeat the egg collection procedure again.

Careful Collection

After a couple of weeks of giving Sarah injections, the doctor checks to see if Sarah’s eggs are ready to be collected. The eggs need to be mature, meaning the sperm can easily fertilize them, for IVF to work.

The doctor performs an ultrasound, which is a scan that allows her to see inside Sarah’s body to check how big the eggs have grown. She also uses a blood test to check Sarah’s estrogen levels. Estrogen is a hormone that becomes more abundant in a female’s body as her eggs grow.

The tests show that Sarah’s eggs are big enough, and her estrogen levels are high, so it’s time to collect.

Sarah lays on a hospital bed, and is given a drug that lets her sleep through the procedure, which is often painful. Then, the doctor, watching her work with the help of an ultrasound, inserts a probe with a long, thin needle attached.

She punctures Sarah’s ovaries with the needle, and an attached suction tool sucks the eggs out. Sarah’s eggs are immediately put in an incubator to keep them alive.

The procedure was quick–only about 20 minutes. Sarah wakes up groggy, but happy it’s over.

Facilitating Fertilization

A scientist might monitor the growth of a fertilized egg by watching it divide. Of the fertilized eggs, typically only 50% will reach an important stage of growth. Doctors will then transfer those into the uterus for implantation. Image by Galina Fomina via Wikimedia Commons

The doctor moves on to the next step pretty quickly. She chooses the eggs that look the healthiest and most mature, then puts those eggs in a glass petri dish along with a sperm sample from Sarah’s partner.

While in the petri dish, some sperm should be able to fertilize some eggs. The fertilized eggs should start dividing. The doctor leaves the petri dishes in an incubator overnight to give the sperm and eggs enough time for this process.

The doctor looks at the eggs under a microscope the next afternoon. Rather than just a single cell, she sees that some of the eggs have divided into two, or even four. Good–that means she and Sarah can move on to the next step.

Introducing Implantation

Doctors often insert multiple embryos into a patient during IVF to increase the chances that one of the embryos will attach to the uterus. But, oftentimes, more than one embryo attaches. That’s why many people who go through IVF end up having twins, or even triplets. Image by 3194556 via pixabay.

Four days later, the doctor gives Sarah another hormone treatment. This treatment helps thicken the lining of Sarah’s uterus so it can support a growing embryo.

The next day, it’s time for implantation. This procedure isn’t as uncomfortable, so Sarah can stay awake for it.

Watching with an ultrasound again, the doctor uses a soft, hollow tube to transfer multiple embryos into Sarah’s uterus. Hopefully, one of the embryos will attach to the wall of Sarah’s uterus, where it will be able to keep growing.

But, they won’t be able to test if that happened for at least nine more days. Sarah goes home after the procedure, nervous but hopeful.

Nine days pass, and then Sarah goes to the doctor’s office to take a test to see if the embryo implantation was successful. Hours later, the doctor checks the results. The procedure was a success!

At-home pegnancy tests like this one detect hormones in a person's urine that only appear during pregnancy. But for people going through IVF, who receive lots of hormone injections to prepare, at-home tests are not the most reliable. Instead, doctors usually test a person's blood to see if they are pregnant after going through IVF. Image by RDNE Stock project via Pexels.

The doctor calls Sarah excitedly to tell her the wonderful news: Sarah is pregnant.

Making Pregnancy Possible

As of 2023, IVF is the most common Assisted Reproductive Technology, or ART. ARTs are methods that may help some couples with infertility get pregnant.

IVF doesn’t always work like it did with Sarah, but it still helps millions of couples each year.

IVF hasn’t always been around, though. The process of developing it took many decades.

IVF in Animals

Before we ever even attempted to use IVF for humans, we tested it on other animals.

The first recorded case of successful IVF fertilization was in black rabbits. A white rabbit gave birth to a baby black rabbit, similar to the one above. This was possible because the embryo implanted into the white rabbit was fertilized in vitro by two black rabbits. Image by Peter Starčević via Pexel

In 1934, researchers Gregory Pincus and Ernst Vinzenz Enzmann decided to attempt IVF on a rabbit. Though the rabbit successfully gave birth, scientists later found that the sperm and egg did not fertilize in vitro. Actually, the egg fertilized inside the uterus, after it was transplanted back into the rabbit. So, this was not technically IVF.

However, in 1959, researcher Min Chueh Chang made a major breakthrough. Working in the US, he performed IVF using the eggs and sperm from two black rabbits. Instead of transplanting the fused embryo back into the female black rabbit, he planted it in a female white rabbit.

A white rabbit usually gives birth to a baby white rabbit. However, the white rabbit gave birth to a baby black rabbit, meaning it gave birth to the embryo that Chang implanted in it. The experiment was a success.

Once researchers saw the success of IVF in these animals, they decided to use the procedure to help humans.

IVF in Humans

Have you heard the name “test-tube baby” before? You might be wondering where the name comes from.

Well, in 1968, Patrick Steptoe, a doctor, and Robert Edwards, a professor and scientist, teamed up to attempt IVF in humans. They were able to successfully fuse an egg and sperm cell together in vitro. But they couldn’t figure out how to successfully implant the fertilized egg into a female uterus.

Even though IVF has helped millions of people have children, it doesn’t always work. A lot of time, money, and effort goes into all ARTs, including IVF. Unsuccessful IVF can be very difficult on an individual and their family. This is one of the risks with IVF. Image by William Fortunato via Pexel.

In 1976, Edwards, Steptoe, and Jean Purdy, a nurse and scientist who studied embryos, began working with Leslie and John Brown. They were a couple who struggled with infertility.

After trial and error, Steptoe and Purdy finally found a way to successfully implant the fertilized egg. In 1978, they helped the Browns get pregnant using IVF. At birth, the Browns named their baby Louise.

Steptoe and Purdy made fertilization happen in a petri dish, but the media called Louise Brown the world’s first “test-tube baby.” Even today, that nickname has stuck.

Since the birth of Louise Brown, millions of babies have been born worldwide through IVF treatment. As scientists improve the methods involved in IVF, they help countless infertile people to have children of their own.

Image of Cryopreservation by SozvezdieL via Wikimedia Commons.

This Embryo Tale was edited by Risa Aria Schnebly and Megha Pillai and is based on the following Embryo Project articles:

Buettner, K.A. (2007, November 8). Min Chueh Chang (1908-1991). Embryo Project Encyclopedia. ISSN: 1940-5030 http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/1667.

Buttar, A. (2008, November 24). Gregory Goodwin Pincus (1903-1967). Embryo Project Encyclopedia. ISSN: 1940-5030 http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/1664.

Cartwright, J. (2019, June 3). Vegas Baby (2016). Embryo Project Encyclopedia. ISSN: 1940-5030 http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/13106.

Danielson, A. (2009, June 10). Patrick Christopher Steptoe (1913-1988). Embryo Project Encyclopedia. ISSN: 1940-5030 http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/1759.

Darby, A., and Abboud, A.J. (2017, November 28). Action of MER-25 and of Clomiphene on the Human Ovary (1963). Embryo Project Encyclopedia. ISSN: 1940-5030 http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/13018.

Jiang, L. (2011, May 12). Robert Geoffrey Edwards and Patrick Christopher Steptoe's Clinical Research in Human in vitro Fertilization and Embryo Transfer, 1969-1980. Embryo Project Encyclopedia. ISSN: 1940-5030 http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/2279.

Philbrick, S. (2011, June 20). Robert Geoffrey Edwards (1925-2013). Embryo Project Encyclopedia. ISSN: 1940-5030 http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/1764.

Zhu, T. (2009, July 22). Assisted Reproductive Technologies. Embryo Project Encyclopedia . ISSN: 1940-5030 http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/1979.

Zhu, T. (2009, July 25). Clomiphene Citrate. Embryo Project Encyclopedia. ISSN: 1940-5030 http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/1997.

Zhu, Tian. (2009, July 22). In Vitro Fertilization. Embryo Project Encyclopedia. ISSN: 1940-5030 http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/1665.

External Sources:

Artal-Mittelmark, R. (2022, September). Stages of Development of the Fetus. Merck Manual Consumer Version.https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/women-s-health-issues/normal-pregnancy/stages-of-development-of-the-fetus

Gosden, R. (2018). Jean Marian Purdy remembered – the hidden life of an IVF pioneer. Human Fertility, 21(2), 86–89.

Infertility. (2023, April 26). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/infertility/index.htm#:~:text=Is%20infertility%20a%20common%20problem,year%20of%20trying%20(infertility).

Mayo Clinic Staff. (2021, September 10). In vitro fertilization (IVF). Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/in-vitro-fertilization/about/pac-20384716

National Institutes of Health Staff. (2018). How Common is Infertility? U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/infertility/conditioninfo/common

NYU Langone Health.(2023) In Vitro Fertilizaiton. https://nyulangone.org/locations/fertility-center/in-vitro-fertilization-egg-freezing-embryo-banking/in-vitro-fertilization

Penn Medicine. (2020, April 20). A Step-By-Step Look at the IVF Process. https://www.pennmedicine.org/updates/blogs/fertility-blog/2020/april/how-does-the-ivf-process-work

PFCLA. (2017, January 17). Are you a good candidate for IVF? Pacific Fertility Center of Los Angeles. https://www.pfcla.com/blog/are-you-a-good-candidate-for-ivf

PFCLA. (2021, April 27).The complete guide to IVF embryo transfers. Pacific Fertility Center of Los Angeles. https://www.pfcla.com/blog/embryo-transfers

View Citation

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Investigating In Vitro Fertilization

- Author(s): Tazeen Ulhaque, Whitney Alexandria Tuoti

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: August 8, 2023

- Date accessed: July 15, 2024

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/embryo-tales/ivf

APA Style

Tazeen Ulhaque, Whitney Alexandria Tuoti. (2023, August 08). Investigating In Vitro Fertilization. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved July 15, 2024 from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/embryo-tales/ivf

Chicago Manual of Style

Tazeen Ulhaque, Whitney Alexandria Tuoti. "Investigating In Vitro Fertilization". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 08 August, 2023. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/embryo-tales/ivf

Tazeen Ulhaque, Whitney Alexandria Tuoti. "Investigating In Vitro Fertilization". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 08 Aug 2023. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. 15 Jul 2024. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/embryo-tales/ivf

MLA 2017 Style

Multiple eggs might be fertilized during the IVF process, but patients only need one to get pregnant. Doctors often freeze those extra eggs. Some are saved in case the patient needs to go through IVF again, but thousands are donated to other couples every year.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.