Living With a Stone Age Brain

Podcast Interview with Doug Kenrick and David Lundberg-Kenrick

Dr. Biology:

This is Ask A Biologist. A program about the living world. And I'm Dr. Biology. Let's go back way back in time to the Stone Age, when life was, let's say, a bit different than today. Now, even though stone tools were the latest and greatest technology life and what motivated humans was very much the same as what motivates us today.

[Fast forward sound effect, followed by keyboard typing, mouse clicks and computer beeping sounds.]

Fast forward to the current world where stone tools have been replaced by modern gadgets and are made of metal and plastic and glass. And more and more, they're controlled by digital brains that make our lives so much better. Or do they? And has our technology filled world evolved faster than our brains? My guests today have some insight into those questions and about our modern world and how our brains are dealing with the rapid changes in technology and society.

Doug Kenrick is a professor in the Department of Psychology at Arizona State University, and David Lundberg. Kenrick is the media outreach program manager, also in the Department of Psychology at ASU. The two are the authors of the book Solving Modern Problems with a Stone Age, Brain, Human Evolution and the Seven Fundamental Motives for This episode, we plan to take a moment to explore what our brains still desire from Stone Age life but might be struggling to fit into our modern world.

And I'll give you a hint it affects our diet, friendships, love, family, and more. Oh, and we have a bit of a brain treat today because one of our guests is also one of the hosts of the Zombified podcast. What's that you might be asking? Well, listen in to find out. Welcome, Doug, to Ask A Biologist.

[Background sounds fade.]

Doug:

Great to be here.

Dr. Biology:

And David, thank you for taking time out to be here.

David:

Yeah, of course. Thanks for having us.

Dr. Biology:

Let me just start off and because the title of the book, right, Solving Modern Problems with a Stone Age Brain and being the academics that you are, you have to have that colon, Human Evolution and the Seven Fundamental Motives. Let's talk a little bit about a Stone Age brain. First of all, what is the Stone Age?

David:

So, this is interesting because we picked Stone Age brain and the reason we picked that title was because a lot of our evolved mechanisms that are still influencing our choices our behaviors, our desires evolved over this very long period before sort of the modern industrial and technical and agricultural revolutions. So, you can't really say, ah, there was this one moment where everyone's brains suddenly became exactly like they are today. And then it stopped.

Dr. Biology:

Right. When you say Stone Age brain, it's really when we started using stone tools. The reality is we have a brain that is struggling with the modern age.

David:

Yeah, I think so.

Dr. Biology:

It's almost like I wouldn't say handicap, but there's this residual mode of the brain that as I was reading the book, I'm thinking, oh, that's why those things are happening.

David:

Yeah, right.

Dr. Biology:

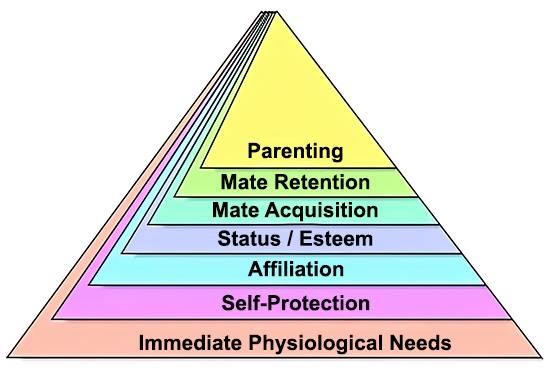

So, let's talk just a little bit about the seven fundamental motives. Can we just do a quick summary?

David:

So, the seven motives are immediate needs, self-protection, affiliation, which is friendship, status, mate acquisition, mate retention and kin care.

Dr. Biology:

Perfect. So where did this list of motives come from?

Doug:

So, there is in psychology this classic kind of pyramid of human motives. And the argument was that as you grow up, you confront different kinds of problems. When you're a baby, all you concern with is having your diaper dry and getting milk and being cuddled when you're cold.

Okay, then you get a little older, you go into preschool, you're concerned with strangers. There's like around age one, when kids start to toddle, they suddenly become afraid of strangers. And that's kind of a universal thing. And then a little bit later, they become attracted to other kids and want to play.

And then still later, they became concerned with how those kids think about them. Do they look up to them or looked down on them? They'd be very concerned with status. And then after that, once we reach puberty, we become concerned with finding mates. And then once you've found a mate, you have a new problem keeping that mate, which isn't true of most mammals.

97% of mammals don't have bonds the way that humans do, but humans do. Then at the top of our pyramid is caring for your family. Because from an evolutionary perspective, what the name of the game is basically getting your genes into future generations.

Now, we don't consciously think that what we consciously think about our ancestors had a little checklist. First, they want to survive, got to feed themselves. Then not step on a poisonous bug. Then they've got to protect themselves from the bad guys. And there were lots of bad guys. Things were kind of nasty in the ancient environment. Then they need to care for their friends. They need to make sure they have a network of friends because humans as naked apes running around on the savannas of Africa, we didn't do so well on our own. But you get ten of us together throwing stones. We could protect ourselves from even major predators and bring down big animals. So, friendship is extremely important.

There's an anthropologist here at ASU, Kim Hill, who actually analyzed the number of calories that are brought in by tribal groups living in South America. And what he and Magdalena Hurtado found is that the average family doesn't always bring in enough calories to prevent themselves from starving, but they have alliances with their cousins and their second cousins, and their in-laws and they share food. So that's like a risk pool. So, we're here because we're a social being individually, not that powerful in a group. We have all kinds of great things going on.

Now, the other part of the checklist is once you've got some friends, you want to get some respect, you want them to value. You don't want to look down on you and think you're a worthless member of the group who isn't doing anything. So, you want to get some respect. You want to develop some skills that they will look up to and say, oh, Dave knows how to fish. He can teach me how to fish. Okay. And then another part of the checklist is to find a mate, which wasn't the same problem for our ancestors as it is. There weren't that many choices as there are now, but then keeping the mate and then taking care of the family. Now, what's interesting is that we face all of those exact same problems today, but our brains evolved under different circumstances.

So, there's what we call a mismatch, an evolutionary mismatch that our brains expect to live in a group that are related to us, that are friends for a lifetime, and where we don't have that many mating opportunities. There's maybe a dozen people going to meet in our life that we could find as a mate. And now here we are in the modern world. And, wow, in some ways we think it's better, we don't have to starve, we've got tons of food, we've got Hershey bars and Ben and Jerry's ice cream and potato chips and all these wonderful things that can keep us from starving, but that makes a new problem because the United Nations now says that many more people die from diseases related to obesity.

Dr. Biology:

Right.

Doug:

From starvation.

Dr. Biology:

Right diet, actually, diet is one of the things that I wanted to talk about. Let's talk a little bit more about what we have today and what we were doing in the past and how there's that mismatch.

David:

Sure. So, diet is a perfect example. Food insecurity is becoming rarer and rarer all the time. We're now at a point where people are actually more likely to die from too much food rather than problems caused by food scarcity. Now, part of the reason for that is people aren't starving.

The other problem, though, is that a lot of the foods that we're eating are not the healthiest for us. And the way foods have sort of quote unquote, evolved to match our needs is really interesting because it shows people like foods that are high in sugar, right? We're evolved to want foods that are high in sugar and high in fat. And if you ever read a wilderness survival guide, it'll say bring foods that are high in sugar and high in fat because they're really hard to find in nature. So when you find them, eat them all.

But now we have really good technology for producing sugary fatty foods that taste delicious. And so, we can eat more of them than we should, which I think people are sort of aware of. But even being aware of it, it's hard, right? You can know it's not good for you, but you see that food and it's really hard to avoid.

Dr. Biology:

Right. So that's that control that that becomes a challenge. It's not necessarily that sugary foods, foods high in fat are a problem for us. It's the quantity that we are consuming. Right. Right.

Doug:

And it's the fact that we simply never lived in that kind of an environment. There simply weren't supermarkets in ancestral environment, and there wasn't anything as fatty and sugary as Ben and Jerry's ice cream. And so, our ancestral brains, even though consciously we know there's a problem with obesity, we can't help it if you put it in front of me.

Okay. As I was writing this book, David, I can both attest to this. During the COVID era, I went to the supermarket, got a whole bunch of chocolate covered cherries, and I thought, this is healthy, it's chocolate, it's good.

David:

It's got fruit.

Doug:

Is fruit in the middle of it. And I put it on my counter, and I gained several pounds. Despite the fact I'm writing this book, talking about these issues, I can't walk through the kitchen and look at chocolate covered cherries and not eat them. And so, one of the things we talked about in the book is how do we deal with these problems? So, if you're like most people and in fact, the majority of Americans apparently now weigh more than they should.

And how do you deal with it? Well, one thing psychologists have this concept called stimulus control. The punch line of the research was done by behaviorists during the last century. But basically, the research is for this purpose is it's very hard to resist temptation. When we see some desirable appetited stimulus. We want to eat it. And so the trick is to control your environment. The trick is not to have the stimuli there. Don't put chocolates on the counter, don't have them in your office or whatever. Don't have them in your school lunch bag, for example. And also, Dave, suggestion sometimes just make yourself work.

David:

Right. So, this is the other half of stimulus control, right? One is you make the undesirable options difficult, but you also make the healthier. And healthier in the sense of food, but healthier in sense of whatever you want, whether you're controlling food or screen time or whatever you make.

Yeah, you're making the desirable habits easier and more rewarding. So, one thing we often do in my house, which sounds kind of silly, but all of us love candy, me and my kids, if we get a candy that is like little bags of candy, we'll actually hide them, right? Will hide them around the house. And then it's like, if you want candy, you got to search. Right? That actually is sort of mimicking the ancestral environment a little bit.

And then the other version is only buying a certain amount at the store. And even if you live near a convenience store and you're like, Oh, I got to walk to the convenience store every time I want to buy a candy bar. That's another way to match that environment, right? The walk will seem pleasurable because, you know, you get that candy bar at the end, or you get that coffee or whatever the thing is that you like. But you've got to first do that little bit of sort of searching and foraging before you get it.

Dr. Biology:

So, I see the importance of this and the challenges you have. There's another one of the things on the checklist that is very challenging today. And it's again, I think, a really big mismatch and that's finding and keeping love. So, who wants to take that one on?

Doug:

The thing that's different is that in the ancestral environment, there weren't that many options. If you were 13, 14, 15 years old. Okay. Girls tended to find mates earlier than boys, but you only had a few choices and often your family would arrange it or something along those lines. But now there's these apps. Then even teenagers have dating apps that they can go on and find teenagers from other cities. So, you can look at hundreds and hundreds of potential partners. And one of the dangers of this is what we call parasitism. We have this strong desire and then that incentivizes someone else to maybe take advantage of that desire.

And so, we talk about in the book a guy named Giovanni Vigliotti, who ended up marrying 105 different women. It was in Arizona where he spent his time. He ended his life in prison here because that's where they caught him. Vigliotti would marry the woman and then take her money and her belongings and disappear into the night. So online there is that danger that someone and teenagers fall prey to this too, that there's someone who's pretending to be something that they're not a potentially good romantic partner and they're not. So that's a bit of a danger that we have in the modern world that we didn't have and the ancestral environment.

David:

So, in some ways the challenge for relationships might be the opposite of the challenge for sugary foods. Where the solution is the opposite in the modern world. Whereas you might want to hide sugary snacks, you might want to keep your partners where you can see them in real life. We actually have a lot of societal mechanisms, like having people meet your family, right? Having people meet your friends. These are ways to sort of assess, especially if somebody is looking for a long-term partner because there's different sort of partnerships. People can be looking for. Right. And if somebody is looking for a long-term partner, it sort of pays to meet their family, have them meet your family and build those connections that will encourage long term partnership.

Doug:

And so, you know, the person in the same sense, our piece of advice there is to shop locally, if you can.

David:

If Yeah, yeah.

Doug:

Rather than to scan the Internet for options there and you know, some of this it's hard to do because there are all these possibilities out there.

David:

I also think in the modern era there is this way that through apps and things like this, dating has become particularly gamified, right? They use things like you get little alerts if somebody likes you. And that combination, I think, puts a lot of pressure on everybody to try to think of dating as this sort of game where you're trying to maximize your ability to get the best or the most possible dates. Right. And that's a lot different than what we're sort of designed for. And also, that's not going to necessarily go hand in hand with long term relationships which have health benefits and things like this. I think also avoiding the idea of thinking of love as a video game is a really good strategy for everybody.

Dr. Biology:

Doug, you mentioned the mismatch. Are there any modern problems that match with our Stone Age brain?

Doug:

That's a good question. I think family care is sort of the same. It works the way it used to work. You know, when people have kids, like when Dave had kids, his mom and I, who are split up, that she moved back here to be near them and his mother-in-law moved here to be done. So, I think there's a natural tendency for us to congregate with our kin, and that's similar to the ancestral environment.

Now, the problem is it's still a little mismatch because there is also the very easy to get on a plane and go someplace else. And in fact, for people, once they have kids, if the mother moves nearby, they can get on a plane and take a job in another city after that. So, it's not exactly the same. But I think the sort of the feelings and the feelings we have towards our family are similar. I think affiliation is similar in many ways. You know, we like the people around us and we like people who share similarities with us. And so, it isn't like everything is off. Okay?

A lot of the things are the same, or at least similar, for example, like the fear of outsiders. Now that's an interesting one, actually. I want to say that that's actually maybe a big mismatch because outsiders --the two things we often think of the bad guys coming over the hill to burn the village, but they also traded with members of other groups. So, our ancestors didn't just fight with one another, and they had cooperative and conflicted relationships with one another. And so, we still have that same ambivalence, I think, towards outsiders. There are potential sources of benefits for us, but also, we don't trust them as much as we trust our local family members. And that can be problematic in a world in which you work at a place like Arizona State University, the people in the biology department and the psychology department in the anthropology department, they come from different places.

They're members of different tribes who might say they come from all different parts of the world, and it pays to get along with them. And so, to some extent, being aware of the fact that we have a natural hesitancy about people who are not well known to us and learning how to overcome that. That's an interesting problem in the modern world, that just it's similar to the ancestral environment, but not exactly the same.

One of the things that's interesting is, despite the news that you hear is that we're way less likely to get killed by people than we used to be in the ancestral environment. Again, Kim Hill, anthropologist, has done some research and looked at the homicide rates in these different groups. And there's a lot of debate about this. But everybody that I speak to the really knows about it. The homicide rates in a peaceful hunter gatherer group were higher than the homicide rates in the most violent city in this very violent country relative to other developed countries where one of the most violent. And so, we are not as threatened by people. They're not as dangerous as we think they are. Why do we think they're dangerous? This is where the mismatch does come in because we want to know. I want to know, is there a threat out there? Is there a dangerous person who might get me or who might hurt my children or who might hurt my family members?

And so, I read the newspaper and I will actually reinforce The New York Times or Fox News or whoever it is I use as my news source for giving me scary news. So, I hear about people being killed all around the world now, and I never would have heard that in the ancestral environment. So now, even though we're safer than we used to be, we probably don't feel any safer. We may even feel less safe.

Dr. Biology:

Right. And being a little bit on the cynical side, it seems that those news outlets have learned that something that we gravitate towards and so they feed more of that to us. I don't even know if it's cynical in some sense. They're kind of like Ben and Jerry's. They're giving us what we want. We buy it, okay?

And they will increase the news stories just like Ben and Jerry's will put more chocolate. And more chocolate is what we want. The news media will put in more stories about violence if that's what we want to hear about. And sadly, in the same way we buy Ben and Jerry's, we buy scary news. There was one analysis that looked at the most popular news headlines over a like a 20-year period. And of the top six of them, five were bad news. In other words, we buy it. You might even say we're our own worst enemies when it comes to some of this.

David:

Yeah.

Doug:

It's our motives that drive the market.

Dr. Biology:

So, your book from its cover and its title, it turns out to be an amazing self-help book. However, one of the things that I noted is it has science backing it. I'm just curious about the process of gathering the science.

David:

So, some of the science comes from a couple of different places. Some is from specifically evolutionary psychology. How are we evolved? Some of it is from general psychology, right? So, some of these studies like helping people, it's just looking at sort of correlational and causal studies about what actually makes people happier because those still hold true because we have science on them. Those are really the two main ones. And behavioral economics.

Doug:

May be like. What we actually are also coauthors of a social psychology textbook. And ever since Dave was a little kid, I had a general psych text and he was 12 years old. He was helping me edit the book. And so, we've been talking about these things and we were talking about research Dave's job at Psych for Life. It's not just about smart people saying things that sound smart like they might on the Oprah Winfrey Show. And some of those people are telling you correct things because sometimes there's debating theories.

You know, the classic theory of economics was do what's right for yourself, you know, get as many resources as you can. And it turns out that that's a bad strategy in real social relationships. You don't want to be counting what you give to your partners. Okay. And there's this funny research that shows that economists do worse in games when they're basically trying to win money. And they have the possibility of you know, like the prisoner's dilemma, where you do better. If you don't act completely selfishly, economists can't do it. But non economists can. So, there's research evidence that pits these different theories against each other. And so that's kind of what Dave does with Psych for Life and it's kind of like what we do in this social psych book.

David:

So, I would actually say the science of behavior change is in and of itself this emerging field, right? Psychology has often looked at just why do we do what we do? And then figuring out how to translate that into, well, how do we do what will actually benefit us? Is a whole other big question that we I think as a scientific community, we're really just starting to get a sense of specifically what sorts of things should people do with this knowledge, what works, what works.

Doug:

What works and what does, because some stuff doesn't work. Let me just add one other thing that classically psychology was associated with treating people who had serious problems depression, major depression and schizophrenia, you know, extreme levels of anxiety that let them not go out of the house. There's a development the last 20, 30 years called positive psychology, which is basically just trying to look at let's do some research, not just on the things that cause us to break down, but let's do some research on the things that cause us to be more fulfilled, more courageous, more creative.

And it turns out that science can be applied. And people used to think, oh, that's all sort of just, you know, you go with your feelings false. You know, science can be applied to these seemingly ethereal topics. Science can be applied to love. Okay, what exactly is love? What are the circumstances under which it does well or doesn't do so well? There's actually good research on the question you were before. What is the difference between couples who are fighting with one another and who get along with one another? We actually know the answer to some of these things now, and that's becoming more and more of a thing. Trying to scientifically ask the question of compare the different alternatives, the different hunches that we have. Some of them are right, some of them are wrong. And so that's where a lot of this comes from.

David:

I just want to give one quick sort of answer to the question of how do we use science to determine what people should do? And I actually think our coauthor, Bob Cialdini, has this term full cycle psychology, which is you start in the lab, you come up with a theory of behavior, right? We think people should do this because of this.

And that can be based on evolution, that can be based on whatever you want. Then you go out and you test it out in the real world. And you see, if you give someone a dollar, are they more likely to do you a favor in return? Right. And then you take that back to the lab to write that up and to turn that into sort of a scientific paper. And I think that's the best way to sort of ensure that you have things that are sound in terms of scientific theory, but then also really hold up out in the real world is to test them out in the real world.

Dr. Biology:

Right. And as Doug said, there are competing theories that all science disciplines have. And so, when you're consuming information from a scientist and or anyone else, it's always good to dig a little deeper to find out what is the background. And this is what I'm really getting at is used to say trust but verify. Well, now I'm kind of saying, well, verify, then trust.

Right. And so, it's an interesting thing that in today's environment that we need to do a little more due diligence.

David:

Can I offer one caveat, though, in terms of this idea of this trust, but verify. The stories that we use right. They're illustrative and everybody's situation is different. And this is one of the key takeaways that I hope people take from this book is that life is about tradeoffs. And assessing consciously assessing what tradeoffs are right for you is really important. Right? You can look and see that this is what works for this group, this is what worked for this other person in this case study. You should then look at this and say, well, are these factors the same for me and what do I want? That's one of the key things I would hope people take away is don't live exactly like anybody that we mention in the book, just use them as examples while you assess what works.

Dr. Biology:

So, on that note, we move to a section of this podcast where I ask three questions of all my guests. I'll start with Doug. The first question is, when did you first know you wanted to be a scientist?

Doug:

I was very young, okay? I was in grammar school, and I grew up in the fifties. And so, I think being a scientist then was very, very highly valued in American society. It was the era before we had gone to the moon, and I was interested in biology. I liked animals, and in fact, I in my life toyed with becoming a biologist, then an anthropologist then a psychologist. What's very nice about evolutionary psych, it's all three of these things. But you know, I liked insects, I liked birds, and I liked nature. And so very early on, I used to read books about science. When I was a kid, I remember reading books about the Raymond Dart's research on trying to discover the missing link is what they used to refer to it as the other, other primates on the way to human beings. And I found all that stuff fascinating.

Dr. Biology:

Right, David?

David:

That's an interesting question for me. So, I have a film background, right? And I think of myself as someone who has always been interested in communication. But also, what drew me to this was film theory and hearing about these different motives, thinking about how they could apply to what we find compelling in movies. And so, I think being raised by a scientist, I've always been drawn to how do we test ideas, right?

And I think that that's something that when people learn those sorts of techniques, it's really important to look and say, all right, will this work? Will that work? And I think I've always been really interested in testing different variations and seeing what works, not really in a lab setting, I think, honestly how I became a scientist, I think, is the world is changing in such a way where whatever you do, you need to collect data and you need to be able to analyze data and you need to be able to use that data to determine what works and what doesn't. Because when I think about my current job, at psyche for life. We're all about seeing if somebody tries this module, does it help their life? If somebody tries this module, does it help their life? Right. And so, I think we're just moving towards a world where everybody's got to do some science.

Doug:

So, when we started writing this book, we actually were writing a book to kind of blend Dave's interest in film and my interest in psychology, because David had this idea that when he looks at these movies, that the themes that you see in great movies and in great novels are actually the same kinds of themes that we and our ancestors had to deal with.

Harry Potter, he's really, he's down at the bottom of the heap, okay? He's being treated like dirt. His parents are dead. He's disconnected from his family. Same thing with Katniss Everdeen. Her father is dead. She can't get food. And there's these gigantic status differences. There's the people in Katniss, Everdeen's life. There's the people in District one, and she's in this sort of, you know, mining district where they don't have any resources or any status and they're looked down upon.

And so, the name of these stories is often going from a position where you don't have your family with you and having to cooperate with a group of friends in order to move up and get ahead in life. And so, a lot of why we find great literature is so engaging and why, you know, even kids get so turned on by these stories, it's because they're tapping into these exact kinds of problems that humans have always had.

Our brain we get excited by, Oh, how do you do that? What if, in fact, you've lost all your relatives and there's bad guys out to get you? What do you do?

And I think the other big thing they tap into with these seven motives is these tradeoffs. Right. How do you accomplish all of these? How do you protect the people you care about and what do you do when you have to choose between gaining status and protecting the people you care about? That's the thing I think Harry Potter always worries about The Hunger Games. You know, Katniss Everdeen, she could win The Hunger Games easily by killing Peeta, but she likes Peeta. And so, all these sort of questions of choosing different mates and choosing between these different aspects of our lives, I think is really fascinating in movies and in life.

Dr. Biology:

Absolutely. And now that we know where the two of you got started in science and even a bit more, for this next question I am going to take it all away. What would you be or do if I took it all away and you were able to pick a different career?

David:

I have two that pop into my head right away and they're connected and both of them are pretty far. Well, at first glance, might seem pretty far from what I'm doing now. One is a farmer. I really like the idea of just living out in the middle of nowhere and living off the land at home. I'm always trying to grow things in my garden. And then the other thing, if I was going to just magically switch into a career that I feel is super important and that I think I would find really fulfilling, is figuring out water infrastructure. I think that that is such an important goal these days, and I would just love to be trying to figure out how to get water from the ocean to the desert and go throughout the world. So those would be the two I would be interested in.

Dr. Biology:

And they're both really good ones and they're both tied to science. You can't be a farmer without being a good scientist.

David:

Absolutely.

Dr. Biology:

And the water infrastructure, we're going to have our engineers and everything in there.

David:

Yes.

Dr. Biology:

So, you can have either one of those. All right, Doug, you got to think about this for a moment.

Doug:

I actually think that --- so I'm friends with John Alcock, who studies insects and is a good birdwatcher. I could see being an ornithologist, to tell you the truth. I mean, I don't have specific great skills at it. You know, I started off majoring in biology in college. And if I had known about what John Alcock did, that might be what I would be doing.

Dr. Biology:

Yeah, right. John was a guest on Ask A Biologist as well. Yes. And has written for us. He's quite a well-known author, both in the textbook world and in the popular science world.

All right. So, the last question, what advice would you have for someone who wants to become a scientist or a psychologist?

Doug:

What advice would I have? Well, I have a teenage son who's just starting ASU. He is going to be an architect. At least that's his plan. Now, he's not really sure. But when I look at people of his generation, if I were to say if you wanted to be a researcher, I could give you very practical advice, work in labs and so forth.

But I think one of the things is enjoy yourself, enjoy the learning. You know, it's like, look, our brain is designed to want to solve, as you pointed out, even young kids, we're always solving let that go free. Okay? Take courses that are really fun for you. And then when you find something that's really the most fun, then that's what you should do. I'm still working well past retirement age, and that's because I love what I do. Just in the same way that kids love computer games.

Okay? I love being able to write, but solely because I don't have a lot of skills. I couldn't have been a farmer, okay? I couldn't have been an athlete. A lot of the things I couldn't do, I'm not tough enough to be a cop or something. And so, it turns out that I was good with words. Okay? And so, I thought of being a writer. That was my second answer would have been to be like a novelist or something like that. The other thing that there's the famous Ben Hogan, quote, Golf is a game of luck. The more I practice, the luckier I get.

And so, you pick the thing that you love and spend a lot of time on it. Try to do the best, not in a competitive way, but in a self-improvement way. It's like just enjoy the process of learning the thing that you love the most, and then that will probably take you a long way.

Dr. Biology:

All right, David, what would you...

David:

One thing I would say is don't be limited by the current jobs that exist. When I was a kid and I went to film school, people were shooting film on actual film stock. And when that changed to digital, it changed not only the way movies were made, but the way movies are watched. Now people watch short things on phone, they listen to podcasts, all these sorts of things. And the world is going to keep changing fast. And a lot of the jobs that you may wish you could have don't even exist now are going to exist.

So, I would say learn advancing technology. These days I would say learn statistics, learn about A.I., learn about like GPT three and these sort of AR programs. A lot of them are not that complicated, if that's what you're interested in. But then I would also say talk to people and find ways to work in labs. We have in the psych department programs for high school students to come in and intern. So going and talking to your science teacher or whatever subject, if you're interested in politics, go and talk to your history teacher and try to figure out ways to think about using new technology to change governments or whatever. So, I would say really dream big and then figure out what tools you need to make it happen.

Dr. Biology:

Now David, before you go, I have one more question. Can we talk a little bit about the Zombified Podcast?

David:

So Zombified is really fun because this is this podcast where we talk about all the ways we're manipulated by things ranging from disease to technology. So, it was started by Doctor Athena Aktipis and she has grown it out. So now there's even a live stream, YouTube channel, channel Z and we have a show on apocalypse medicine, and we have a show on food in the apocalypse. And it's just this sort of fun way to hear about these different scientific things. And often we will talk about movies. It's just a really fun way to talk about science, you know?

Dr. Biology:

Well, I certainly recommend that people try out Zombified. We’ll be sure to include a link in the show notes to make it easier to find the podcast.

And on that final note and a really fun conversation, I want to thank you David.

David:

Thank you.

Dr. Biology:

And Doug, thank you so much for sitting down with me.

Doug:

Thank you. It's fun to talk to you.

Dr. Biology:

You have been listening to Ask A Biologist. and my guests have been Doug Kenrick and David Lundberg-Kenrick. They are the authors of the book Solving Modern Problems with the Stone Age, Brain, Human Evolution, and the Seven Fundamental Motives.

Now we'll be sure to add a link to the book for those who want to learn how to navigate the modern world with our Stone Age brain. Also, be sure to check out the episode notes and transcript for additional links to content we talked about in the show, including a link to the Zombified Podcast. And for those who listen to us using an app that shows chapter links and images, we often include helpful pictures and illustrations for many of the links.

The Ask A Biologist. podcast is produced on the campus of Arizona State University and is recorded in the Grassroots Studio housed in the School of Life Sciences, which is an academic unit of The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. And remember, even though our program is not broadcast live, you can still send us your questions about biology using our companion website. The address is askabiologist.asu.edu or you can just Google the words 'Ask A Biologist'.

As always, I'm Dr. Biology and I hope you're staying safe and healthy.

View Citation

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Living With a Stone Age Brain

- Episode number: 120

- Author(s): Dr. Biology

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Date published: August 11, 2022

- Date accessed: September 27, 2024

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/living-stone-age-brain

APA Style

Dr. Biology. (2022, August 11). Living With a Stone Age Brain (120) [Audio podcast Episode.] In Ask A Biologist Podcast. Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/living-stone-age-brain

Chicago Manual of Style

Dr. Biology. "Living With a Stone Age Brain." Produced by Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist. Ask A Biologist Podcast. August 11, 2022. Podcast, MP3 audio. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/living-stone-age-brain.

MLA Style

"Living With a Stone Age Brain." Ask A Biologist Podcast from Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist, 11 August, 2022, askabiologist.asu.edu/living-stone-age-brain.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.